eBook - ePub

Tackling Causes and Consequences of Health Inequalities

A Practical Guide

- 346 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tackling Causes and Consequences of Health Inequalities

A Practical Guide

About this book

Addressing health inequalities is a key focus for health and social care organizations. This book explores how best frontline health workers in areas of deprivation can address these problems. Aimed at doctors and their wider multidisciplinary teams, this book provides key knowledge and practical advice on how to address the causes and consequences of health inequalities to achieve better outcomes for patients. Considering the psychological, financial and social aspects of well-being as well as health concerns, this book offers a concise but comprehensive overview of the key issues in health inequalities and, most importantly, how practically to address them.

Key Features

- Comprehensively covers the breadth of subjects identified by RCGP's work to formulate a curriculum for health inequalities

-

- The first book to address the urgent area of causes and consequences of health inequalities in clinical practice.

-

- Chapters are authored by expert practitioners with proven experience in each aspect of health care.

-

- Applied, practical focus, demonstrating approaches that will work and can be applied in 'every' situation of inequality.

-

- Provides evidence of how community based primary care can make a change.

-

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tackling Causes and Consequences of Health Inequalities by James Matheson, John Patterson, Laura Neilson, James Matheson,John Patterson,Laura Neilson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medizin & Familien- & Hausarztpraxis. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART 1

Setting the Scene

1 An Insight from the Front Line

Laura Neilson

2 An Introduction to Health Inequalities

Ann Marie Connolly

3 A Multi-level Approach to Treating Social Risks to Health for Health Providers

Gary Bloch and Ritika Goel

4 A Tale of Two Cities – Hull and York

Ben Jackson and Mark Purvis

1

An Insight from the Front Line

Laura Neilson

It doesn’t take into account the vulnerability, the trauma, the deficit of love, the overwhelming need for acceptance, the potent power of being totally broke. It is more than choice.

I’m guessing that if you are reading this book, then you already have a passing interest in health inequalities and know some of the topics mentioned here, but recaps can never hurt.

On a simple level, health inequalities are simply the difference in health outcomes, the morbidity or mortality of one population compared to another, usually comparing richer demographics with those less well off. The beginning of this thinking really emerged with Tudor Hart and his inverse care law, published in 1971 in The Lancet:

The availability of good medical care tends to vary inversely with the need for it in the population served. This inverse care law operates more completely where medical care is most exposed to market forces, and less so where such exposure is reduced.

This idea landed in the medical community like a firecracker. If Twitter in the digital world is harsh, then it pales when reading the comments and letters from fellow medics sent to The Lancet from 1971 onwards. Black, Acheson and Whitehall all contributed to a growing understanding of inequalities. More recently heroes such as Marmot, Wilkinson, Pickett and Watt have picked up the mantle. These giants of academic research, detailed analytics, critical and forensic thinking, continue to describe and prove health inequalities are prevalent and present. They continue to call out the injustice and refuse to allow the establishment and the individual to deceive themselves that all is right. The inconvenient truth is that all is not alright.

In the UK there is potent inequality. Within all areas of the country there is a gradient along income levels. Those with the most money have the healthiest, happiest, most secure lives with the most years of disease-free living and they live longer. Those who are poorest have shorter lives with more disease and more burdens. You can see the difference in life expectancy of over 10 years across one area or even one town. In parts of London the differences are evident across the distance of three tube stops. Or even more soberingly, in one tower block. We see inequality by ethnicity, by education, by access to green space, by type of job. The academics can show us whatever way we ask for. The inequality is still there.

Theory of Inequality

How these inequalities come to be so great, is the debate of many a clever thinker. The life-course theory suggests that they notch up over the course of a life. Those born into poverty often go on to experience poverty. We know that antenatal health has a huge impact on the foetus and child at birth. The impact of the first 1,000 days on life outcomes is a key piece of academic work that should shape our policies and investment. The impact of childhood trauma is only just being fully realised, and the newly emerging field of epigenetics is both thrilling and terrifying at the same time. Life events often throw people into poverty and there is increasing work describing the importance of resilience and social networks as buffers for the effects of life events. Simple explanations of choice and behaviour are usually popular with politicians, but they don’t quite cut the mustard in the real world; think about the woman who has gotten out of one domestic violent relationship only to get into another. Choice isn’t quite the right understanding of the situation. It doesn’t take into account the vulnerability, the trauma, the deficit of love, the overwhelming need for acceptance, the potent power of being totally broke. It is more than choice. Other theories of economic or political empowerment explain some inequalities: social determinants of health offer the most all-encompassing evidence base for consideration and pscyho-social theories give insight to individual or family stories. Macroeconomics, structural injustice, reduction in social mobility – there are papers upon papers listing theories and evidence. All interesting, all useful, all have their place. But, the pervasive, persistent plod of poverty is still there and what do you do as a practitioner in the field?

The Cake Approach

During the first few years of my working in deprivation, interventions to tackle health inequalities were aimed at specific groups of people. These usually covered groups like the homeless, travelling communities, sex workers, refugees and asylum seekers, perhaps people with learning disabilities and more recently veterans.

Indeed, I had set up and continue to run work for these groups of people and there is nothing wrong with them; they are needed and do great work. And yet when I looked at the estate I lived and worked on, even if I did an intervention for each category of people, it did not touch the majority of the population. It did not shift our health outcomes. It was like having a massive cake and slicing off a piece for asylum seekers, sex workers, travellers. Once you had finished slicing you assumed there would be no cake left. Only you realised there was still a massive hunk on the plate. Where we lived and worked there was just a whole load of people in poverty and that was the defining characteristic. So, we started to think about the cake differently.

In fact we started to think about a bubble.

The Inequality Bubble

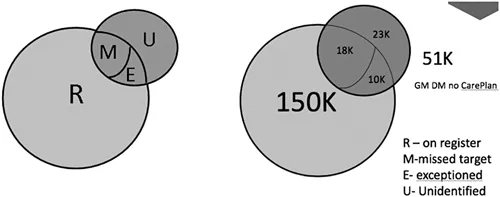

We took diabetes and started to look at health outcomes. In Manchester there are an estimated 150,000 people with diabetes. Of these, 18,000 have high HBA1c levels so they are outside the target, a further 10,000 are ‘exceptioned’ by general practice. Patients can be ‘exceptioned’ because they are terminally ill, in prison or other reasons. Whatever the reason, they are unlikely to have well controlled diabetes. No one ‘exceptions’ patients who hit the target! And then there are approximately an extra 23,000 patients who had diabetes but are not yet diagnosed. In total in Greater Manchester there are 51,000 diabetics who do not have a working care plan for diabetes (Figure 1.1).

What puts you into this 51,000 people is interesting. It seems you got into this bubble if you were poor, if you were in a domestic violent (DV) relationship, if you were known to the law, if you were an immigrant, if you had a learning disability, an addiction, mental health problem, if you had temporary housing or no housing. In summary you got into this bubble if you had a factor of inequality, and the fact you are in the bubble perpetuates the inequality.

Think of it like a football with a massive rip in it (Figure 1.2).

No wonder we never seemed to hit the goal of meeting health targets, or reducing inequalities. That football is never going to score a goal.

Turns out the bubble is the same whatever the chronic disease, and the things that put you in the bubble are the same. We started thinking of health inequalities as:

Health inequalities is ‘failure to thrive’ multiplied by ‘barriers to universal services’ exacerbated by ‘social determinants of health’ (verbally said as Fit Bus SD)

Suddenly health inequalities weren’t about groups of people and a deficit fixed with simp...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Editors

- Contributors

- Introduction

- PART 1 SETTING THE SCENE

- PART 2 KNOWLEDGE AND SKILLS

- PART 3 POPULATIONS AND GROUPS

- PART 4 SUCCESSFUL MODELS OF LEARNING AND PRACTICE

- Index