![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

This book represents for us the culmination of a decade of clinical research with aggressive and psychopathic personalities. Our thinking has been shaped by clinical experience and theoretical writings concerning the severe personality disorders. As collaborators our styles have been complementary. Reid Meloy has always been the theoretician and clinician firmly grounded in traditional psychoanalytic writings. His early career work was largely with schizophrenic patients in a variety of clinical settings, and then shifted to male and female adult criminal populations in maximum security settings. Carl Gacono’s thinking sprung from clinical observations of conduct-disordered children during play therapy, adolescent delinquents in multifamily treatment groups, psychotherapy with antisocial personality disordered (ASPD) adults, and the administration of hundreds of Rorschachs and Revised Psychopathy Checklists (PCL–Rs).1 Theories have provided descriptions for and incisive understanding of what we have observed with patients; and our observations, in turn, have prompted us to delineate and expand the boundaries of theory.2

The chapters of this book evolved from empirical data, and in the style of Cleckley (1976), compose a clinical and research textbook where observation and theory converge. We hope our case examples and large-group studies provide clinicians with fascinating, sound, and useful data that will stand the test of time. For every question answered, however, several more beg to be asked.

When we coauthored our first article (Gacono & Meloy, 1988), and individually authored a dissertation (Gacono, 1988) and a book (Meloy, 1988), subsequent collaborative research was only a pleasant, unfulfilled inchoate wish. The strength of our friendship and commitment to the study of violence and psychopathy has sustained our 10-year collaboration. We have never had research grants, and continue to have none at present, but have managed to bootleg research time from our other clinical obligations. This Rorschach work has truly been a “labor of love,” which only those fortunate enough to become enamored with the richness and complexity of those 10 inkblots will understand.

Our research subjects are a different story. We both have had extensive clinical experience with these loveless individuals held in county jails, state prisons, forensic hospitals, and private psychiatric hospitals. These subjects elicit extreme, and usually negative, countertransference reactions from both clinicians and society.

Adult institutions are distinguished by their relatively high frequency of psychopathic residents. Best estimates are that approximately 23% of male inmates and 11% of male forensic psychiatric inpatients would meet our criteria for psychopathy, or what has been traditionally known as the Cleckley psychopath (Cleckley, 1976/1941; Hare, 1991). Prevalence rates for women are three to five times less, given the gender-related aspect of psychopathy.3

These “failed” psychopaths, by virtue of their incarceration, have been the focus of a large amount of clinical attention during the past century, but not until relatively recently has there been an empirically sound measure of the construct psychopathy (Hare, 1980, 1985, 1991; see chapter 5 for a review). The PCL–R (Hare, 1991) has catalyzed research during the past decade by providing a reliable and valid method for classifying adults as psychopathic or not. The 20-item scale (see Table 1.1) functions well as an independent classification from which other dependent measures, such as the Rorschach, can be taken. It is this simple methodology that has shaped much of our work, and will inform future endeavors.

TABLE 1.1

The Psychopathy Checklist–Revised

1. | Glibness/superficial charm |

2. | Grandiose sense of self-worth |

3. | Need for stimulation/proneness to boredom |

4. | Pathological lying |

5. | Conning/manipulative |

6. | Lack of remorse or guilt |

7. | Shallow affect |

8. | Callous/lack of empthy |

9. | Parasitic lifestyle |

10. | Poor behavioral controls |

11. | Promiscuous sexual behavior |

12. | Early behavior problems |

13. | Lack of realistic, long-term goals |

14. | Impulsivity |

15. | Irresponsibility |

16. | Failure to accept responsibility for own actions |

17. | Many short-term marital relationships |

18. | Juvenile delinquency |

19. | Revocation of conditional release |

20. | Criminal versatility |

Note. From Hare (1991). Copyright 1991 by Multihealth Systems Inc. Reprinted by permission.

But isn’t it enough to know that these are bad people who do bad things? We think not. The ascendancy of the socially deviant model of antisocial behavior, most apparent in the DSM–II–IV series of the American Psychiatric Association (APA, 1968, 1980, 1987, 1994), has supported the notion that to describe behavior of antisocial individuals is enough. But what this model has failed to satisfy is clinical understanding of the disorder. A search for clinical knowledge leads to questions of motivation and meaning, prompting further inquiry into the thought organization, affective life, defensive operations, impulses, and object relations of psychopaths and other aggressive individuals.

Our work, then, becomes another logical contribution to understanding psychopathy and aggression. It is our best effort to psychometrically “map” the intrapsychic life of these subjects, and those aggressive children and adolescents we consider at risk for the later development of psychopathic character.

THE RORSCHACH

We selected the Rorschach as our dependent measure and primary investigative tool for a variety of reasons. First, we both have had extensive training in its administration and interpretation. Carl Gacono’s graduate studies included Rorschach training with James Madero, PhD, utilizing the Comprehensive System, Kwawer’s (1980) borderline object relations categories, and the Lerner and Lerner (1980) defense scales. Subsequently, he trained and consulted with Phil Erdberg and Paul Lerner. Reid Meloy was originally taught the Rorschach by Sidney Smith, PhD, during his graduate studies, utilizing the methodology of Rapaport, Gill, and Schafer (1945) and the form-level scoring of Martin Mayman, PhD. He subsequently was trained in the Comprehensive System through Rorschach Workshops, his principal teachers being Phil Erdberg, John Exner, Jr., and Irving Weiner. Both of us received our doctorates in clinical psychology from United States International University.

Second, the Rorschach itself is ranked eighth among psychological tests used in a national survey of outpatient mental health facilities (Piotrowski & Keller, 1989). It is the second most widely used test with adolescent patients, and is the most popular projective technique with this population (Archer, Maruish, Imhof, & Piotrowski, 1991). It is also the second most widely used psychological test by members of the Society for Personality Assessment, an international organization of psychological scientists and practitioners (Piotrowski, Sherry, & Keller, 1985). Watkins (1991) reviewed 30 years of survey studies (1960–1990) of psychological assessment and found that the Rorschach was one of the most frequently used and consistently mentioned psychological tests in most clinical settings, was one of the most popular instruments, along with the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), to research, and has received continuing emphasis in most clinical psychology training programs. In forensic evaluations, psychiatrists will specifically request the use of the Rorschach approximately 25% of the time (Rogers & Cavanaugh, 1983). It is a psychological test that has weathered the vicissitudes of time and opinion quite well.

Third, the five most common scoring systems for the Rorschach have been integrated and standardized over the past 30 years by John Exner, Jr., culminating in the Comprehensive System, a reliable and valid interpretive methodology for understanding the Rorschach. We would like to acknowledge Dr. Exner’s enormous contribution to Rorschach science, and our indebtedness to his accomplishments concerning the Rorschach and personality structure.

Fourth, developments parallel to the Comprehensive System have occurred within the psychoanalytic community. Psychoanalytically trained psychologists have charted new territory by attempting to understand the content of the Rorschach with empirical methods consistent with psychoanalytic theory. These methods have generally focused upon object relations (Blatt & Lerner, 1983; Kwawer, 1979, 1980), defenses (Cooper, Perry, & Arnow, 1988; Lerner & Lerner, 1980), development and psychopathology (Urist, 1977), and thought organization (Athey, 1974; Meloy & Singer, 1991). Much of the psychoanalytic Rorschach research since the late 1970s is signified in four books (Kissen, 1986; Kwawer, Lerner, Lerner, & Sugarman, 1980; Lerner, 1991; Lerner & Lerner, 1988).

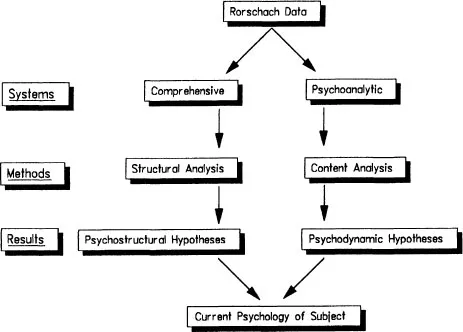

Fifth, our work has attempted to integrate both a structural and content understanding of the Rorschach (Erdberg, 1993) by applying several different scoring systems and methods to our research protocols. We think this approach, wherein the Comprehensive System (Exner, 1986a) is used to understand psychostructure and various psychoanalytic methods are used to understand psychodynamics, is most fruitful, and has yielded both important nomothetic (Gacono et al., 1992) and idiographic (Gacono, 1992; Meloy, 1992b; Meloy & Gacono, 1992b) findings. Our approach is illustrated in Fig. 1.1.

FIG. 1.1. Approach to the Rorschach data.

Sixth, self-report measures with criminal populations are notoriously unreliable (Hare, 1991). In both clinical and research settings, when the subject is a forensic patient, the psychologist is wise to minimize the use of self-report tests. Only those tests with robust measures of distortion, such as the MMPI and MMPI–2 (Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, Version 2), should be considered. Self-report tests with high face validity, such as the Beck Depression Inventory, should be assiduously avoided, unless they are being purposefully used to measure distortion by comparing them with other less obvious measures. The Rorschach is unique in the sense that it is a perceptual-associative-judgmental task that partially bypasses volitional controls, yet yields important data, some of which are projected material (Meloy, 1991b). We have also found, contrary to our expectations, that psychopaths generally produce a normat...