![]()

One

What is corporate sustainability?

All men have stars, but they are not the same things for different people. For some, who are travelers, the stars are guides. For others they are no more than little lights in the sky. For others, who are scholars, they are problems... But all these stars are silent.

Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, writer, poet, philosopher, and aviator

Sustainability has different meanings for different people. It has different meanings in different contexts. It has different meanings at different points of time: in the past, at present, and in the future. The meaning of sustainability is constantly evolving, sometimes slowly and sometimes in great leaps and bounds as new knowledge is created and scientific discoveries made. For example, knowledge about the impact of chemicals on human health, the depletion of the Earth’s ozone layer, the impact of greenhouse gases on global warming, the thinning of the polar ice caps, global warming and rise in ocean levels, the impact of industrial pollution on air and water quality, habitats, and species, has evolved constantly over the last five decades.

In this book, sustainability refers to resilience and the longevity of our ecosystems (which includes minerals, vegetation, oceans, atmosphere, climate, water bodies, and biodiversity), society (which includes culture, languages, and quality of life) and economy. A sustainable world is one in which the human race enjoys a high quality of life in an equitable and just society and a thriving ecosystem that includes a biodiversity of plants and animals, and clean atmosphere/ air, water, soils, and oceans. The concept of a sustainable world may sound utopian and perhaps impossible to achieve. However, it is difficult to argue that this is an ideal not worth striving for. If we reverse the argument, it would be difficult for a rational person to adopt a position that economic growth and prosperity is worthwhile at all costs including deteriorating air and water quality, growth of diseases and cancers, destruction of species, destruction of nature, decreased quality of life, and increasing social injustice and inequality. Ecosystems, society, and the economy are intertwined and interdependent. Businesses are embedded in, draw from, and affect society and the environment. While all sectors—governments, communities, consumers, civil society, and business—have a role to play in the journey toward the ideal of a sustainable world, this book is about the role of business.

Managers are exposed to, and sometimes bombarded with, multiple terms in the media with different meanings attributed to sustainability. Different consultants often use the terms differently. Some of the terms used include corporate social responsibility (CSR), corporate citizenship, greening, sustainable development, and corporate sustainability. The term in vogue may vary depending on the country or region. While all these terms refer to one or more aspects of a firm’s strategy and actions intended to address its social and environmental impacts, there are some differences. Understanding these differences helps managers engage in meaningful dialogue with different stakeholders and constituents in order to define a problem domain, develop effective strategies, and generate successful sustainable innovations.

In Australia, New Zealand, and many Western European countries, CSR is used synonymously with corporate sustainability. In other contexts, CSR refers to a firm assuming responsibility for the impacts that society deems as negative or unacceptable, rather than fundamentally changing its strategy and operations to generate positive social and environmental impacts. The negative social and environmental impacts that a responsible firm needs to address are a moving target. This is because society’s perspectives about which impacts of business’s operations are negative are constantly evolving. For example, societal perceptions about emissions of waste from manufacturing facilities have changed substantially over the last five decades. Visual representations such as smokestacks represented economic development in the 1950s, but they now represent air pollution for most people across the world.

The term “corporate citizenship” is usually used to describe a firm’s role in, or responsibility toward, society. In some contexts, it is used interchangeably with CSR and some companies use it to describe their social and community initiatives. Some firms emphasize the term “corporate philanthropy”. Corporate philanthropy usually refers to corporate giving or donations intended to mitigate government failures in addressing social needs, problems, and challenges. Another term used in various contexts is corporate greening. Greening refers to actions adopted by firms to reduce negative impacts on the natural environment and usually does not focus on negative social impacts.

Regardless of how these terms are actually used by firms, or are defined by scholars, none of these—CSR, citizenship, or philan-thropy—necessarily implies that the firm will change its core operations or strategies. Usually, these terms are used to describe a firm’s practices and actions to mitigate the impacts of its operations that society deems negative. As compared to the terms discussed above, corporate sustainability as defined in this book has fundamental implications for business strategy. In this book corporate sustainability refers to a firm’s strategy that enables it to achieve positive economic, social, and environmental performance. As highlighted above, it may not be possible for any organization to be truly and completely sustainable. Rather, corporate sustainability is a journey on which an increasing number of organizations have embarked.

The term “sustainable” is a derivation of the term “sustainable development” that was coined by the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). The WCED, more popularly known as the Brundtland Commission (after its Chair, Gro Harlem Brundt-land) was created by the United Nations in 1983 to address growing concern about the accelerating deterioration of the human environment and natural resources and its consequences for economic and social development. In its report, Our Common Future, published in 1987, the WCED coined the most often-quoted definition of sustainable development as development that “meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”1 This definition placed economic development within the context of resources (natural environment) and also within the context of balancing development in the present and in the future, and equity between societal groups and across generations.

The WCED definition called for businesses to adopt three principles of sustainability: sustainability of resource extraction—should not exceed the capacity of natural systems to regenerate resources such as forests, fisheries, soil, clean water, etc.; sustainability of waste generation—should not exceed the carrying capacity of natural systems to absorb them; and social equity—business activities should have a positive impact on poverty reduction, distribution of income, and human rights. Hence, this definition is relevant to corporate sustainability and the role of business in sustainable development, as defined in this book.

Karl-Henrik Robèrt, a Swedish oncologist, translated the WCED definition into system conditions for sustainability via the Natural Step Framework in 1989. These four conditions called for eliminating humanity’s contribution to the progressive build-up of substances extracted from the Earth’s crust; eliminating humanity’s contribution to the progressive build-up of chemicals and compounds; eliminating humanity’s contribution to the progressive physical degradation and destruction of nature and natural processes; and eliminating humanity’s contribution to conditions that undermine people’s capacity to meet their basic human needs.

These central elements of sustainable development as proposed by WCED and the Natural Step are fairly similar. However, they are relatively easy to visualize at a global, national or a societal level but are much more difficult for an individual firm to measure and implement. At the firm level, sustainability can be broadly translated into strategies that lead to the achievement of its short-term financial, social, and environmental performance without compromising its long-term financial, social, and environmental performance. This means that the firm needs to create value for its stakeholders in the present while investing in strategies and resources to improve the social, environmental, and economic performance desired by its stakeholders (including its shareholders) in the future. In this process, the firm has to manage the uncertainty related to the evolving and changing definition of “value” over time for its various stakeholders.

A sustainable organization is one that changes its business or its strategy to achieve not only its economic or core objectives (for example, for a nonprofit organization, the core objective may be the delivery of healthcare or clean water rather than profits), but also its social and environmental performance. Hence, a sustainable organization is significantly different from a firm that does not fundamentally change its business model or strategy but rather acts responsibly by adopting practices to mitigate the negative social and environmental impacts of its existing operations. How firms can undertake the journey to transform themselves into sustainable organizations is the focus of this book.

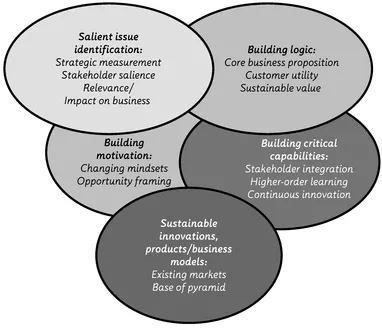

Building capacity for sustainable innovation

Building a sustainable organization requires a firm to analyze and fundamentally change its strategy in order to deliver both short-term and long-term economic, social, and environmental performance as per the expectations of its various stakeholders, including its investors and shareholders. An effective strategy to generate and implement successful sustainable innovations requires the firm to:

- Identify relevant and material sustainability issues

- Understand linkages between sustainable practices and competitive advantage

- Build business logic for a sustainable strategy

- Build managerial motivations

- Build critical capabilities

Identifying relevant and material sustainability issues requires the generation of data on the firm’s sustainability impacts that need to be addressed by a strategic analysis of the firm’s sustainability footprint. This includes measuring and benchmarking a firm’s social and environmental footprint in addition to its economic metrics based on salience of issues that are important for the firm’s stakeholders and estimating the impacts of these issues on current and future business (Chapter 2). Before developing a strategy, managers need to understand the risks of following an unsustainable strategy and the linkage between a sustainable strategy and competitive advantage (Chapter 3). Building logic requires an understanding of how sustainable value generates corporate value in terms of enhancing the core utilities for the customers served by the firm (Chapter 4). Building managerial motivations requires changing mind-sets and creating an opportunity frame to motivate employees to become change agents for a sustainable organization (Chapter 5). Building critical capabilities involves embedding unique processes within the firm to engage and integrate stakeholders, generate information and higher order learning, and generate continuous innovation of processes, products, services and business models that enhance triple bottom-line performance and enable the firm to compete in the future in existing markets (Chapter 6), and the co-creation of sustainable business models for the unserved and under-served four billion people at the base of the pyramid (Chapter 7). Figure 1.1 graphically depicts the building blocks of a sustainable organization. As the figure shows, the logic, motivations, and capabilities closely interact to produce sustainable innovations and these innovations in turn impact the logic, motivations, and capabilities. Finally, Chapter 9 offers a vision for the next steps forward in enabling businesses to leverage their resources on this journey toward a sustainable economy.

Figure 1.1 The building blocks of a sustainable organization

Summary

A sustainable organization develops core strategies and business models for the achievement of its short-term financial, social, and environmental goals without compromising its ability to compete in the future on its long-term financial, social, and environmental goals. This contrasts with concepts such as corporate social responsibility and corporate citizenship that emphasize investing in practices to mitigate or reduce the negative social and environmental impacts of the organization’s existing operations. Table 1.1 highlights the differences among terms commonly used to refer to an organization’s actions to address its social and environmental impacts.

Table 1.1 Terms used within the domain of corporate su...