![]()

1

Government’s Embrace

Governments are important to organization, establishing and enforcing the rules under which organizations operate. They can make a course of action profitable or illegal. Governments may be stable guarantors of open and fair dealing, or they may be bumbling inept entities unable to control even their own officials. Governments facilitate the establishment and enforcement of the fundamental understandings necessary to action: who is entitled to what uses (use rights); who may legitimately sell products, land, and equipment (ownership rights); and what actions are acceptable (contract law). They are extraordinarily various, ranging from centuries-old tradition-encrusted institutions to the bandit in control of a small region, with every imaginable variation in between. Yet however various they are in form and practice, governments are always important to organizations and their participants. They establish the rules by which organizations must play and have the means to use physical force to coerce compliance.

Because those who operate and work within organizations must always contend with the governments ruling over them, it is remarkable that government is virtually invisible in theories of organization and management. Certainly it has become a truism that economic activity is enmeshed in institutions (Polányi, 1957). That is, individuals act in the context of their expectations about the meaning and effects of their actions. Yet governments have not figured prominently in the institutions examined by theorists of organizations, organizational behavior, or management. Social institutions (Granovetter, 1985), cultural ones (Hofstede, 1980a) and historical experiences (Guillén, 1994) have received scholarly attention, whereas the effects from different forms of sovereign government are only rarely noted.

To illustrate, corruption among government officials has been widely discussed in the popular management press but rarely addressed or explained in the scholarly organization and management literature. Yet surely the ability (or requirement) to avoid the enforcement of inconvenient laws results in different organizational strategies, organizational practices, and attitudes and behavior of participants than what would obtain in a society wherein enforcement of the rule of law is strict and assured. Economists have sought to analyze corruption as a cost of business, but rarely have organization and management scholars analyzed how corruption affects the way the participants organize their work and their relationships with one another. Moreover, corruption is just one example; the same strange silence confronts such government practices as erratic and opaque laws and regulations, requirements that organizations take state-owned partners into their ventures, or the practice of favoring cronies and family members in government contracting, among others. Despite O’Reilly’s (1991) call for more sociologic and conceptual explanation in organizational behavior, such explanations have been scarce, a situation this work is intended to address.

Certainly, the fact that scholarship and research is dominated by those living in societies with comparatively strong, predictable, and supportive governments has played a part in this omission. Because governments in the societies wherein most scholars work tend to be strong, predictable, and supportive of independent organizations, the only visible scholarly focus on governments concerns differences in the content of particular laws, such as the German requirement, not found in many other developed countries, that large corporations place employee representatives on corporate boards. Yet no one in these societies is uncertain about how such government mandates are created, or doubts that these large corporations must comply with whatever the law requires. Because most scholars are not as familiar with the organizational effects of weak, erratic, and hostile governments, few scholarly theories have been cognizant of how the embrace of government affects management practice, organizations, and organizational behavior.

The arguments presented here are derived from insights gained from the collapse of communism. Communism was an experiment in direct government control over all of the organized activities of a modern society. It can be viewed as an ambitious attempt, in numerous societies with vastly different cultures and histories, to operate in violation of many fundamental social science theories. For example, Parsons and Smelser (1956) argued that a central feature of modernism was the differentiation of societal subsystems, yet communism tried to recombine these subsystems into a single party-controlled one. Weber (1947) feared that the world would be dominated by bureaucracies because of the superiority of their rational pursuit of technical efficiency, yet in communist societies bureaucratic rationality was subordinated to political ideology. Under communism, organizations looked funny, and their participants acted in ways that appeared peculiar to the visitor steeped in knowledge of social science theory and organizational practice in the developed world.

In seeking to learn more about why such unexpected behavior should have occurred, the author learned that the government-driven organizational forms and organizational behavior were not anomalies. Whereas the government interventions in communist countries were stark enough to draw the author’s attention, further research and observation led to the proposition that the effects of governments on management and organization are pervasive, powerful, and underappreciated by scholars in management, organization theory, and organizational behavior.

Practitioners working in such countries certainly appreciate the power of governments, but they have received little explanatory assistance from scholars. Practitioner pamphlets, films, and books provide vivid anecdotes for those struggling with the complex challenges of international work. However, they offer little explanation. Rather, the reader is required to take the differences described as a fact of life and admonished to be sensitive to others’ differences. But surely not in all circumstances. Should Canadian managers adapt themselves to a Javanese view of time as holistic in their factory there? We all know they will do no such thing. Without an understanding of the reasons for particular international differences, useful advice about when to adapt and why cannot be given, nor can predictions about changing practices be made. Anecdotes help to caution new arrivals, but they are limited guides for the long hard work of organizing in countries not your own. Practitioners have been forced to make one ad hoc adjustment after another with no sense of why some may work and others may fail.

This neglect of government’s role in management and organization is becoming an increasingly important problem. Large complex organizations arose with modernization, yet increasing global economic and institutional integration has placed organizations that developed in modernist societies into ones that governments are not willing or capable of supporting. Such spreading internationalization has been followed by a growth in scholarly and professional interest in international management. Whereas the amount of writing about international management increases, useful theories have not kept pace. This is the gap in understanding that this work seeks to fill.

Although some scholars have sought to explain the role of governments in international differences in organizational behavior and practices, with few exceptions, such explanations are specific to a particular country and scattered in various scholarly journals ranging across fields such as political science, sociology, economics, anthropology, and psychology. This makes their insights unusable by practitioners and difficult to access for many organizational scholars. As demonstrated in this volume, governments have powerful effects on the fundamental ways in which organizations operate and on their participants’ expectations, attitudes, and behavior in the workplace. Here the scholarly ideas from these scattered social science disciplines addressing these effects are integrated with the author’s own research into a coherent argument about the effects of government on management practice, organizational form, and individuals’ organizational behavior.

This work is an explanation of how governments’ ability and interest in facilitating independent organization affects organizing and organizational behavior. As governments vary from those that successfully facilitate independent organization to those at the other end of this dimension that actively seeking to impede independent organization. Facilitating governments are supportive, seek to provide predictable laws and regulations that they are capable of enforcing. As govern-ments become less facilitative, the less supportive they are of organizations, and the more unpredictable and weak they become. Although a difference in governments’ facilitation of independent organization is not the only international difference affecting organizations, it is an important one, with powerful implications for organization theory, behavior, and management practice, that has yet to receive a systematic and comprehensive analysis.

In this volume, the focus is on understanding the effects of nonfacilitative government, but it is addressed primarily to scholars and practitioners in rich, developed societies with facilitative governments, for several reasons. First, those living under nonfacilitative governments already know what they face. Rather, it is the scholar or practitioner who has worked only under facilitative governments and implicitly assumes its comforts who most needs assistance in understanding what nonfacilitative governments do to organizations and their participants. When confronted with organizations operating under nonfacilitative governments, they make blunders such as misunderstanding the meaning and uses of introductions, or ignoring the mutual obligations inherent in their local business relationships. Those who do not understand the role of government facilitation in organizations assume that others’ practices must result from ignorance, or from that vague all-purpose cause, cultural differences, instead of viewing them as practices and assumptions that others have found useful in their circumstances.

Second, scholarly theories implicitly assuming facilitative government are partial without recognizing it. The study of organizational theory and behavior under nonfacilitative governments provides insights, elaborations, and modifications of these partial theories developed under facilitative governments. In some cases, this work provides empirical evidence to support and reinforce ideas that have not received broad testing, such as Redding’s (1990) argument that weak and hostile governments lead to organization based on personal relationships. In other cases, it suggests that a theory may be mischaracterizing a phenomenon, with potentially misleading results, as in scholarly descriptions that characterize reliance on mutual dependence in transactions as “trust-based.”

Finally, this work adds new topics and insights to these disciplines, such as the study of employee obsequiousness, harmony in interpersonal interaction, and passivity. Although no scholars of organizational theory and behavior would maintain that governments are irrelevant, it is now time to begin understanding in what way s they are relevant and why.

CHAPTER ORGANIZATION

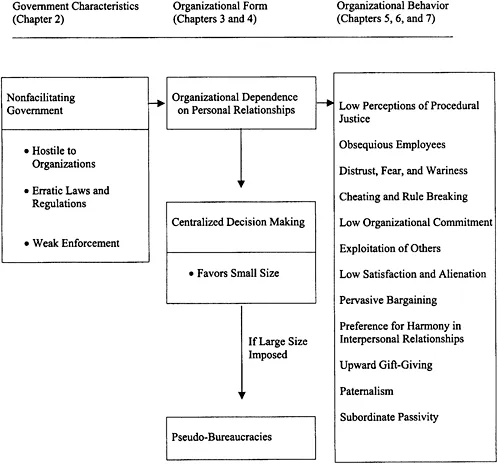

Organizational adaptations to differences in government facilitation have been numerous and significant. Although the central idea is a fairly abstract one, it has substantial implications for many of the most vexing organizational puzzles faced in international management. Figure 1.1 summarizes the arguments to be made, and where possible, tested here.

The central insight developed and illustrated in chapter 2 is that a primary role of government is to facilitate effective complex organization. Among other organizational effects, strong facilitative governments create legal infrastructures and enforcement regimes that allow sufficient advance planning to enable participants to judge whether personal and financial investments are worthwhile, and to rely on more efficient impersonal coordination. Yet not all governments develop and enforce the policies that facilitate such organizational work. Some governments do not do so because they are hostile to independent organizations. Communist governments are extreme examples of hostility to independent organization, but there are many other examples of governments hostile to independent organizations in particular industrial sectors (e.g., oil). Similarly, governments facilitate organization by ensuring predictability in laws and regulation.

Finally, governments may simply be too weak to effectively facilitate organizations. Lack of enforcement can take different forms. Some governments are incapable of enforcing their own laws because they lack organizational skill or control over all their territory. Alternatively, some governments may be unable to control their own local officials, who then are free to hijack local agencies for their own personal use, However, just because governments may not be able or willing to facilitate independent organization, people do not stop organizing because such efforts are not made easier by governments. Rather, they organize as best they can under the constraints they face.

Chapter 3 draws on the work of others such as Redding (1990), who have suggested that individuals adapt themselves to nonfacilitative government by basing their organizations on personal relationships. This adaptation is best documented in the burgeoning study of Chinese guanxi, or relationships. Under nonfacilitative governments, individuals seeking to organize will build the predictability and support they need via their own personal networks by cultivating relationships of mutual dependence with useful others. How such relationships look and how they are built and sustained as the basis for organization is illustrated with empirical and case descriptions from the research of the author and others in a number of countries. The arguments and data presented in this chapter call into question scholars’ use of the term “trust” to characterize transactions based on personal dependence. Such relationships may be characterized by personal warmth and trust, but more often they are wary, distrustful relationships, quite accurately described by the economists’ term “mutual hostages.”

In chapter 4, the effects that a dominance of personal relationships have on the form and practices of organizations operating under nonfacilitative governments are examined. For example, it is proposed that dependence on personal relationships fosters high levels of centralization, because so much depends...