- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1984. The effects of contextual stimuli on the performance of conditioned behaviors have recently become the object of intense theoretical and empirical scrutiny. This book presents the work of researchers who have attempted to characterize the role of context in learning through direct experimental manipulation of these stimuli. Their work reveals that context has important and systematic effects upon the learning and performance of conditioned responses. The roles played by context are diverse and the problems confronted in attempting to evaluate and differentiate contextual functions are formidable. These considerations are discussed in the introductory chapter. The remaining chapters present an analysis of the role of context in Pavlovian, operant, and discrimination learning paradigms.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

The Functions of Context in Learning and Performance

Peter D Balsam

Barnard College of Columbia University

Barnard College of Columbia University

Context

At a logical and procedural level, all learning occurs in context. Learning occurs in a cognitive or associative context of what has been learned before and in an environmental context that is defined by the location, time, and specific features of the task at hand. The chapters of this book focus primarily on the latter meaning of context, although discussions throughout the book make reference to the influence of past learning on present learning and performance. The common assumption of the chapters presented in this volume is the belief that by analyzing the functional control of behavior by physically defined contextual cues we will arrive at a deeper understanding of the laws of learning and performance. The motivation for this collective undertaking arises, in large part, from the failures of traditional association theories.

General problems with traditional association theory have provided the impetus for exploring alternative systems of analysis. As Estes (1976) has pointed out, the structure of these traditional theories (Guthrie, 1935; Hull, 1943; Pavlov, 1927; Skinner, 1938; Thorndike, 1931) consists of an association between two elements. In some cases, both elements are stimuli, and in others the elements are stimuli and responses. As a consequence, the utility of these theories rests solely on the power of binary associations to account for the data. Two general problems provide a challenge to this approach. First, challenges to the notion that only two elements are involved in the associative learning process, and, second, the great difficulty in specifying objectively what the elements or units of association are, in even the simplest sort of learning experiment, has created a need for major revisions in theories of learning.

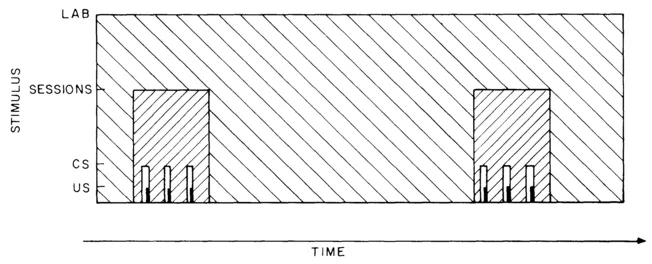

FIG. 1.1. Schematic representation of the hierarchical structure of contexts in a Pavlovian-conditioning experiment. (After Balsam, 1984; copyright Ballinger Publishing Company. Adapted with permission.)

Consider the simple conditioning experiment depicted in Fig. 1.1. Across days subjects are placed into experimental chambers. In the presence of the experimental apparatus conditioned stimuli (CSs) are presented. In the context of a CS unconditioned stimuli (USs) are presented. After a number of such experiences, the CS will evoke a conditioned response (CR). That CR, however, is not solely a reflection of the CS-US association. If that CS is tested in a different context, CR strength will be affected. The effectiveness of that CS is modulated by context-US associations (Durlach, 1982; Gabriel, 1972; McAllister & McAllister, 1965; Randich & Ross, Chapter 5; Rescorla, Durlach, & Grau, Chapter 2; Tomie, Chapter 3), context-CS associations (Rescorla, 1984; Rescorla, Durlach & Grau, Chapter 2), and by the potentiation of CS-US associations by the context (Bouton & Bolles, Chapter 6; Holland, 1983; Miller & Schactman, Chapter 7). A simple associative learning experiment is, therefore, quite complex. There are many first-order associations that influence performance, but even more difficult for simple association theories is the demonstration that a given stimulus may control an excitatory CR, no CR, or even a different CR. depending on the context in which the stimulus appears (Archer, Sjoden, & Nilsson, Chapter 9; Bouton & Bolles, Chapter 6; Hulse, Cynx, & Humpal, Chapter 10; Kaplan & Hearst, Chapter 8; Medin & Reynolds, Chapter 12; Rescorla, Durlach, & Grau, Chapter 2; Thomas, Chapter 11; Tomie, Chapter 3). One function of context, then, is to modulate the strength and type of control that is exerted by stimuli. Such an effect is not easily accommodated by traditional association theories, and several models that are based on hierarchical associative networks have been developed to account for this sort of control (Estes, 1972, 1976; Medin & Reynolds, Chapter 12).

Loosely speaking, context has been invoked in circumstances where it "disambiguates" (Bouton & Bolles, Chapter 6; Thomas, Chapter 11) or gives an ambiguous stimulus meaning. The importance of context is nowhere clearer than in the analysis of relational stimuli. Hulse, Cynx, & Humpal (Chapter 10), for example, have been studying melody perception in starlings. What is the stimulus that the birds learn about? There is no absolute physical feature of the stimuli that is relevant. It is the relation between stimuli that defines the relevant cue. Again, it is only in the context of other stimuli that any stimulus has meaning.

This discussion of how simple association theory fails and how the idea of context has been crucial to the development of learning theory comes quite close to a discussion presented by Kohler (1929). Kohler argued that the formation of perceptual organizations was primarily what associative learning was about. When elements were integrated into an organizational unit, they belonged together (i.e., they were associated). Kohler, furthermore, suggested that the context in which things are presented will be an important determinant of whether or not they are perceived as belonging together.

None of the chapters of this book abandon the language of association for the study of perceptual organization. There is clearly a concerted attempt to build upon the historical foundations of association theory. This book represents work that takes associationistic psychology into new domains. Each of the chapters challenges existing theory and provides new insights and questions about the nature of learning.

The purpose of this chapter is to provide a guide to the remainder of the book. The following sections provide an introduction to the methods of studying context and to the conceptual issues that arise throughout the book.

The Functions of Context

Context has been defined both structurally and functionally by the various contributors to this volume. When it is defined structurally, context generally refers to all the aspects of an experimental environment that are presented concurrently with a conditioned stimulus, including those cues that remain constant throughout a session. When it is defined functionally, it is used to mean any stimulus that modulates the control exerted by other stimuli (Medin & Reynolds, Chapter 12; Thomas, Chapter 11). A number of descriptions have been offered as to how the context influences behavior. Some functions of context imply that it is just like any other cue, whereas other functions are uniquely ascribed to contexts. The various ways in which contexts might function to modulate learning and performance are described in the following.

Competition. Some accounts of the role of contextual cues in learning claim that the context competes with cues for associative strength (Rescorla & Wagner, 1972) or attention (Mackintosh, 1975). In these theories, cues and contexts are functionally equivalent. The competition between them implies that to the extent that one is learned about or attended to the other will suffer. There are other forms of competition, however, that occur between context and cue. Cues and contexts may also compete with one another at a peripheral level. Behavior controlled by the context may interfere with behavior controlled by a cue (Balsam, 1984; Tomie, Chapter 3).

Comparison. Features of cues and contexts may be compared to one another to determine learning and/or performance. In a comprehensive analysis of the major animal learning paradigms, John Gibbon and his colleagues (Gibbon, 1977, 1979; Gibbon & Balsam, 1981; Gibbon & Church, 1984) have proposed that a ratio comparison of an overall delay to reinforcement in a context with a local delay of reinforcement underlies the performance of learned behavior. In nondiscriminated procedures (e.g., reinforcement schedules and Sidman avoidance procedures), subjects compare an estimate of the delay remaining to reinforcement to an estimate of the overall reinforcement delay, whereas, in discriminated procedures (e.g., discrete trial and classical conditioning procedures), subjects compare an average delay of reinforcement in the signal to the overall delay in the context. When this expectancy ratio exceeds a threshold, subjects respond. In this view, subjects learn about both cues and contexts, and performance is a function of the ratio of their expectancy or associative values. Performance is clearly thought to be a function of this ratio at the time of learning, and by implication the same rule may apply if cue and/or context values are altered after initial training. A similar role for context has been proposed for cases of inhibitory learning (Balsam, in press; Kaplan & Hearst, Chapter 8; Miller & Schachtman, Chapter 7).

Summation. In contrast to the comparison function, Konorski (1967) suggested that drive conditioned to contextual cues might summate with the associative value of a CS and thus augment the strength of the CR. This sort of summation of context and CS value has been invoked to explain the facilitated responding that is found when a CS is tested in a context associated with the same US that was used to condition the CS (Bouton & Bolles, Chapter 6; Miller & Schachtman, Chapter 7; Rescorla, Durlach, & Grau, Chapter 2).

Retrieval. A fourth function of context can be to act as a retrieval cue. Such a cue can be part of an association between other stimuli and responses. The probability of recall is, therefore, influenced by whether or not the test context is similar to the training context (Medin & Reynolds, Chapter 12). Context can also serve as a retrieval cue for other associations. For example, Miller and Schachtman (Chapter 7) suggest that context acts as a retrieval cue for a CS-US association. Similarily, a context may act as a retrieval cue for an instrumental CR-US association (Spear, Smith, Bryan, Gordon, Timmons, & Chiszar, 1980). This latter function is quite similar to the one described in the next section, in which context acts like a gate for other associations.

Occasion Setting. This function of context is based on Holland's (1983) analysis of positive and negative feature discriminations. In these arrangements, a cue is repeatedly presented and occasionally reinforced. In a positive feature procedure, this cue is accompanied by a distinct cue on reinforced occasions. In a negative feature procedure, the cue is accompanied by a distinct stimulus when it is not reinforced. These features, therefore, set the occasions on which the common cues will be differently reinforced. In this paradigm, particularly when the distinctive feature precedes the common cue, the feature serves to enable or gate a particular CS-US relationship. Rescorla, Durlach, and Grau (Chapter 2) report a similar result in which a positive feature acts to enable a particular CS-US relationship, independently of the occasion setter's association with the US.

Similarly, the occasion-setting function of a stimulus can gate an instrumental CR-US relationship. This is an alternate description of the discriminative function of stimuli. A discriminative stimulus performs a contextual function in the sense that it signals when a particular response-reinforcer relationship is in effect (Medin & Reynolds, Chapter 12; Overton, Chapter 13; Thomas, Chapter 11).

Response Selection. The context in which a cue is reinforced may also determine the specific form of a conditioned response. Unconditioned or conditioned properties of the context may modulate either the learning or performance of a particular CS-CR connection. For example, Joan Graf, Rae Silver, and I have been studying the development of pecking in young Ring Doves. We have found that after associations between seed and food have been formed, the specific form of the CR depends on the context in which squab are tested. The squab will peck at seed but if they are tested in the presence of their parents they will also beg at the seed, the food-getting behavior that is usually directed at the parents. The form of the CR directed at the CS (seed) is, therefore, modulated by either the conditioned or unconditioned properties of the context.

Tomie (Chapter 3) shows that the form of the CR in autoshaping may be modulated by the strength of the context-US association at the time of learning. A similar effect on response topography is documented later in this chapter.

Stimulus Generalization. The physical context in which a stimulus occurs affects the sensory input and/or perception of that stimulus. It is always the relation between cue and context that defines a physical stimulus. This is true even in situations in which there is a sing...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- 1. The Functions of Context in Learning and Performance

- 2. Contextual Learning in Pavlovian Conditioning

- 3. Effects of Test Context on the Acquisition of Autoshaping to a Formerly Random Keylight or a Formerly Contextual Keylight

- 4. Some Effects of Contextual Conditioning and US Predictability on Pavlovian Conditioning

- 5. Contextual Stimuli Mediate the Effects of Pre- and Postexposure to the Unconditioned Stimulus on Conditioned Suppression

- 6. Contexts, Event-Memories, and Extinction

- 7. The Several Roles of Context at the Time of Retrieval

- 8. Contextual Control and Excitatory Versus Inhibitory Learning: Studies of Extinction, Reinstatement, and Interference

- 9. Contextual Control of Taste-Aversion Conditioning and Extinction

- 10. Pitch Context and Pitch Discrimination by Birds

- 11. Contextual Stimulus Control of Operant Responding in Pigeons

- 12. Cue-Context Interactions in Discrimination, Categorization, and Memory

- 13. Contextual Stimulus Effects of Drugs and Internal States

- 14. Cognitive Maps and Environmental Context

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Context and Learning by P. Balsam,A. Tomie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Experimental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.