- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Behavioral Assessment in School Psychology

About this book

This important volume presents strategies and procedures for assessing both emotional/behavioral problems and academic difficulties. Arranged by assessment content areas, the volume discusses such methodologies as behavioral interviewing, observation, self-monitoring, use of self- and informant-report, and both analogue and curriculum-based assessment. All chapters are supported by numerous examples and illustrations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Behavioral Assessment in School Psychology by Edward S. Shapiro in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

BEHAVIORAL ASSESSMENT IN SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGY

1

ASSESSMENT IN THE SCHOOLS

Assessments in schools are performed for a wide variety of reasons. A school district wishing to decide whether to continue a rather costly remedial reading program may ask for an assessment of student progress and overall cost effectiveness before deciding the fate of the program. A district may set specific priorities for improving instruction based on the results of district-wide achievement tests. A teacher determines a students’ grade in spelling from accumulated scores across tests. Each of these are examples where an assessment is conducted to make decisions. Clearly, the assessment process can have a significant impact on a large portion of the school population.

Group assessment is probably the most frequent type of assessment procedure used in schools. Almost all districts have a testing program in which students are routinely administered standardized achievement and/or aptitude tests. Classroom teachers using informal and teacher-made materials administer group tests to determine student progress. Although these group assessment measures may have direct impact on individuals, school psychologists are much more involved in assessments of individual performance. Used primarily to make decisions regarding an individual child’s educational progress and psychological disposition, this type of assessment leads to changes that may directly affect a child’s life. These changes can range from minor variations in teaching style to sweeping modifications of a child’s school, classroom, educational classification, and possibly home.

It is this latter type of assessment, individual assessment, with which this volume is concerned. Let us begin by examining in more detail the purposes of assessment.

WHY DO WE ASSESS?

Decision Making

Salvia and Ysseldyke (1985) define assessment as, “the process of collecting data for the purpose of (1) specifying and verifying problems, and (2) making decisions about students” (p. 5). Five primary types of decisions that can be made from assessments have been identified. These are decisions about referral, screening, classification, instructional planning, and pupil progress evaluation. For each of these decisions, academic, behavioral, or physical problems may be the targets of assessment.

The interaction of decision type and problem area results in 15 different possible kinds of assessment. Although school psychologists may be involved in any of these, the largest proportion of time spent in assessment by school psychologists usually concerns decisions around classification and instructional planning (Goldwasser & Meyers, 1983). The types of decisions to be made through assessment, however, are not usually specified by the referral source. Teachers refer because they are having a problem with a student and would like assistance. Once referred, a process is begun to understand why the child is having the problems that have lead to the referral and to respond to questions being asked by the referring teacher. Although the referring source does not differentiate the type of decision to be made, each of these decisions should require a differential assessment process (Salvia & Ysseldyke, 1985; Ysseldyke & Mirkin, 1982). It makes little sense to be using instruments designed to make classification decisions to prescribe remediation strategies.

Unfortunately, this has not been the case. Ysseldyke, Algozzine, Regan, and McGue (1981), in a computer simulation, found that a cross-section of educational personnel including school psychologists, regular education teachers, special education teachers, administrators, and pupil personnel support staff (nurses, counselors, speech therapists) all accessed similar information in making classification decisions about a hypothetical case, regardless of the reason for referral. Specifically, intelligence and achievement test data were chosen most often from data available on intelligence, achievement, perceptual-motor, personality, language tests, adaptive behavior scales, several behavioral observations, and behavioral checklists. Further, Ysseldyke et al. (1981) found in their study that the reason for referral (academic vs. behavioral problems) represented the most critical variable in making classification decisions even when all available psychometric data reflected average or normal performance.

In an attempted replication and extension of the Ysseldyke et al. (1981) study, Huebner and Cummings (1985) found contrasting results. Specifically examining the decision making of school psychologists alone, Huebner and Cummings (1985) showed that school psychologists made highly accurate classification decisions. Although the results of this study casts some doubt on the Ysseldyke et al. findings, there were substantial differences in the overall population (school personnel vs. only school psychologists) that may have accounted for the differences.

In another examination of decision making by school psychologists, Thurlow and Ysseldyke (1982), using a survey method, found heavy reliance on psycho-educational tests. Specifically, the WISC-R, Wide Range Achievement Test, and Bender-Gestalt were reported to be the most useful in making recommendations for instructional planning by psychologists whereas the WISC-R, Peabody Individual Achievement test, and Key Math test were reported as the most useful by teachers. These tests, with the exception of the Key Math, were actually being used for a purpose (instructional planning) for which they were not designed (Ysseldyke, 1979).

What appears clear from these studies is that individual assessment may not be truly individual. Whether an educational classification is to be decided or strategies for instruction developed, the child is given a “standard” assessment battery (Ysseldyke, Regan, Thurlow, & Schwartz, 1981). This battery typically consists of an intelligence test, achievement test, evaluation of perceptualmotor skills (e.g., Bender-Gestalt), evaluation of psychoeducational processes such as learning style, modality preference, auditory discrimination, and other tests designed to evaluate a narrow area of cognitive functioning (Goh, Teslow, & Fuller, 1981). Further, the battery will often include tests of personality such as the House-Tree-Person, Human Figure Drawings, and other projective techniques (Fuller & Goh, 1983; Prout, 1983). These test data are usually combined with a developmental and health history, as well as teacher report and behavioral observations. Based on this information, decisions are made regarding educational classification, instructional programming, and possibly pupil progress (e.g., a re-evaluation). Although this “shotgun” approach to assessment and decision making is clearly not appropriate in light of the mandated individual evaluation specified by Public Law 94–142 (Education for All Handicapped Children Act, 1975), the practice is well documented in the literature. Further, as Ysseldyke et al. (1981) Ysseldyke, Algozzine, Richey, and Graden (1982), and Thurlow and Ysseldyke (1982) found in their studies, decisions appear to be made on the basis of factors other than the test data.

CURRENT PRACTICE OF ASSESSMENT

A clear understanding of the present state of assessment in school psychology requires an examination of historical events in the profession that have shaped the current issues and concerns of school psychologists. In particular, the development of nontraditional roles for school psychologists may have had a significant impact on changes in the assessment process.

Traditional and Nontraditional Roles

The school psychologist’s role in the individual assessment process has a well documented past. Although the actual beginning of the discipline of school psychology is unknown, its roots often are traced to the influences of the testing movement, the development of special education, and the mental health movement (Bardon & Bennett, 1974; French, 1984; Tindall, 1979).

The influences of special education and the mental health movement upon the development of school psychology should have provided a basis for school psychologists to develop roles that emphasize intervention as well as assessment. Unfortunately, this has not been the case. School psychologists were born of the necessity for diagnosticians (Sarason, 1976). Well-trained professionals capable of making important educational classification decisions were required. In response to this pressing need, psychologists turned to the tools available at the time, psychological tests. Looking around for techniques to make their decisions more objective and reliable, they found few methods had been developed to refine their decision-making process. As a result, school psychologists began relying on individual intelligence scales, achievement tests, and personality measures in performing assessments. The applicability of this approach to school-based problems was never questioned because most psychologists in schools at the time were trained in a clinical, diagnostic model.

The logic in this model seemed straightforward. Arriving at a diagnostic decision points one toward selection of appropriate treatment techniques. Derived from a medical model, this perspective makes sense. Until one decides whether one has a virus or bacterial infection, the correct medication cannot be prescribed. Borrowing this model and translating to educational terms, it is thought that until one decides whether one is mentally retarded, learning disabled, or emotionally disturbed, the appropriate educational program cannot be prescribed.

Despite the intuitive appeal of this method of decision-making, empirical validation of the method is lacking. By the mid-20th century, the relationship between diagnosis and educational programming was in doubt (Engelmann, 1968). As confirming evidence continued to mount (Arter & Jenkins, 1979; Engelmann, Granzin, & Severson, 1979; Hallahan & Kauffman, 1977; Schenck, 1980), school psychologists began to recognize that their persistent use of a diagnostic model was questionable. Clearly, school psychologists had to reassess their methodology and contribution to the assessment process.

As school psychologists began considering alternatives to their diagnostic model, the profession was undergoing drastic changes. More than any other issue, school psychologists have been searching for professional identity. In the last 30 years, at least five major conferences have been held to deal with, at least in part, the issue of what is a school psychologist. In 1954, the Thayer Conference (Cutts, 1955) established the foundation upon which the field would grow. Bardon (1965), in summarizing the conclusions of a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) sponsored conference, noted the lack of definition of the field, the need for an expanded role, the question whether school psychology was an independent discipline, and the social/political climate of the country as major concerns at the time. Other conferences, the Boulder Conference (Raimy, 1950), the Vail Conference (Korman, 1974), the Spring Hill Symposium (Ysseldyke & Weinberg, 1981), and the Olympia Conference (Brown, Cardon, Coulter, & Meyers, 1982), interestingly have echoed these same initial concerns. Obviously, one would be tempted to ask the question whether anything has actually changed in the past 30 years!

What exactly is this role from which school psychology has been running since its inception as a discipline? The answer to this question often has been implied in the literature but rarely elaborated. In attempting to unravel the nature of the role it can probably best be conceptualized as a psychometric model that views the school psychologist’s primary function to be that of diagnostician. His or her job is to identify children who are in need of special education and to make recommendations for their appropriate educational program. In reality, the job of the school psychologist is to assess those children referred because of academic or behavioral problems and to make a recommendation for placement. Grubb, Petty, and Flynn (1976) have labeled this approach as the refer-test-report-recommend model and the model often has been perceived as the traditional role within which school psychology operates.

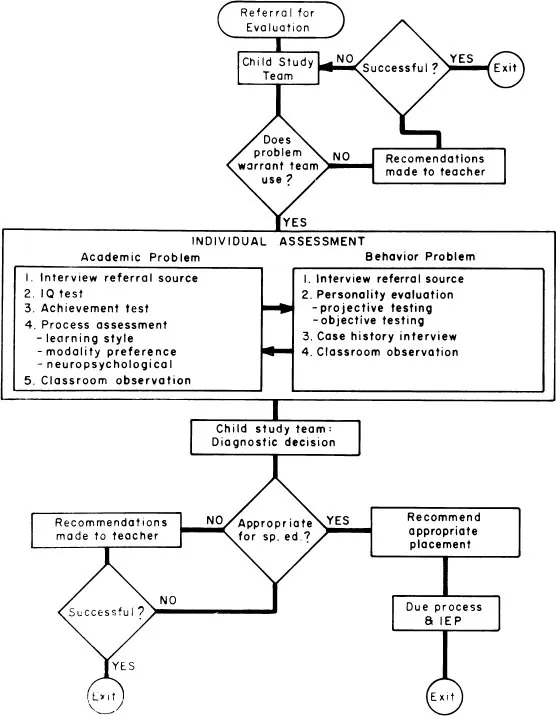

A good illustration of this traditional model of school psychology was provided by Chandler and Siegel (1982) who described the operation of a psycho-educational clinic. Although their model was designed for operation as a university-based training facility, it effectively describes the decision-making process that occurs within a traditional model of school psychology. The psychologist assessing a child who is referred for learning problems proceeds by answering basic questions regarding functioning in cognitive (intellectual), language, psychoneurological, and sensory areas. Each of these areas are usually assessed by administering tests designed to evaluate each area. A similar process is followed when referrals are made for behavioral problems. Both types of processes result in classification decisions. Lentz and Shapiro (1985) also provided an example of the process typically used in a traditional model for the delivery of psychological services in schools (Fig. 1.1).

FIG. 1.1. A traditional model for the delivery of school psychological services. Reproduced with permission from Lentz, F. E., & Shapiro, E. S., Behavioral school psychology. A conceptual model for the delivery of psychological services. In T. R. Kratochwill (Ed.), Advances in School Psychology, vol. IV. (pp. 191–222). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

The prevalence of this model has been well documented. Surveys of school personnel have consistently reported that a large majority of the school psychologist’s time is spent in a diagnostic function. For example, Hughes (1979) in a sample of superintendents, group directors, and school psychologists found that among school psychologists in Virginia, approximately 50–60% of the school psychologist’s time was spent in test administration, test interpretation, and report writing in contrast to 5–7% in classroom observation and 4–6% in mental health consultation. Benson and Hughes (1985), in a survey of psychologists, superintendents, and state departments of education found similar percentages for job functions. Goh, Teslow, and Fuller (1981) in a national survey of school psychologists reported a slightly lower figure of 45–50% of time spent in assessment. Lacayo, Sherwood, and Morris (1981) reported that when school psychologists recorded their daily activities, nearly 40% of actual work time per day was devoted to assessment activities. Gilmore and Chandy (1973a) reported that teachers typically view the school psychologist’s major diagnostic method as testing.

The narrowness of the role definition has long been opposed by most school pyschologists. Surveys commenting on this traditional model have reported dissatisfaction by both consumers of school psychological services and psychologists themselves (Clair & Kiraly, 1971; Gilmore & Chandy, 1973b; Hughes, 1979; Kirschner, 1971; Lesiak & Lounsbury, 1977). As a result, school psychologists have continually been expressing alternative models for the delivery of psychology services. Although a variety of non-traditional roles have been suggested, such as counselor/therapist, inservice trainer, researcher (Monroe, 1979), or vocational evaluator (Hohenshil & Warden, 1978), perhaps the one role viewed as diametrically opposite that of diagnostician is the role of consultant.

The school psychologist adhering to a consultative model does not view his or her role as that of psychometrician. Instead, the psychologist offers his or her skills in assessment, intervention, and understanding human behavior to assist the consultee (usually the teacher) with the referral problem. In this way, the school psychologist is able to offer a much broader range of services to the consumers of school psychology. He or she may spend significantly more time interacting directly with teachers or parents than with the problem child. Additionally, as a consultant, the psychologist’s time is felt to be spent more efficiently. Consultation with a teacher about a ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- PREFACE

- 1 ASSESSMENT IN THE SCHOOLS

- 2 THE METHODOLOGY OF BEHAVIORAL ASSESSMENT

- 3 BEHAVIORAL ASSESSMENT OF ACADEMIC SKILLS: CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK AND OVERVIEW

- 4 ASSESSING READING, MATH, AND WRITING

- 5 ASSESSING BEHAVIORAL AND EMOTIONAL PROBLEMS

- 6 ASSESSING ADAPTIVE BEHAVIOR

- 7 BEHAVIOR CONSULTATION: LINKING ASSESSMENT AND INTERVENTION

- 8 A MODEL FOR DELIVERING SCHOOL PSYCHOLOGICAL SERVICES

- REFERENCES

- AUTHOR INDEX

- SUBJECT INDEX