![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

As transitions towards employment have been extended in recent decades, so too has the period of youthful semi-dependence on adults. While many young people manage successfully to navigate this increasingly complicated course, a large number experience significant difficulties along the way. There is considerable concern that, either as a consequence of these difficulties, or for other reasons, many young people are deciding against, or being prevented from, participating fully in civil society. It is these young people – who encounter significant problems in the worlds of education, training and employment, are often in trouble with the criminal justice system, or exhibit other forms of problematic behaviour – that are often referred to as ‘disaffected’. Responding to, and seeking to prevent or mitigate such difficulties, has become a major focus for public policy. Under New Labour, one of the most talked about (and talked up) forms of intervention with disaffected youth has been ‘mentoring’.

Mentoring generally involves establishing a relationship between two people with the aim of providing role models who will offer advice and guidance in a way that will empower both parties. Mentoring is believed to hold much promise in reducing youth crime and drug and alcohol misuse while promoting social inclusion and attachment to mainstream social values. Indeed, so heavily has it been promoted in recent years that it has become the latest in a long line of ‘silver bullets’. Yet, as is so often the case, there has hitherto been remarkably little empirical evidence on which the efficacy of this approach may be assessed. Early mentoring programmes in this area first developed in the USA. ‘Big Brothers, Big Sisters of America’ has become something of a prototype for mentoring schemes and has been influential in the rapid expansion of mentoring on both sides of the Atlantic. Yet, the most thorough review of the research evidence conducted by Sherman and colleagues (1999) for the National Institute of Justice in Washington, DC found that community-based mentoring programmes could, at best, only be described as ‘promising’. Having reviewed all the evidence, they concluded:

Even with the encouraging findings from the most recent controlled test of community mentoring, there is too little information for adequate policymaking. The priority is for more research, not more unevaluated programs. The danger of doing harm is far too great to promote and fund mentoring on a broad scale without carefully controlled evaluations.

In this book we provide a critical examination of both the idea and the practice of mentoring, and report the results of the first major UK study of mentoring based on the largest and most rigorous research conducted to date. Using a self-report study, with a longitudinal design, the research follows a group of over 300 highly disaffected young people during and after their involvement in mentoring programmes. Together with a large number of in-depth interviews with the young people themselves, with their mentors and with the staff responsible for running the programmes, the study gives a vivid insight into the nature of such disaffection, the realities of contemporary social exclusion among young people and the experience and outcome of mentoring. We begin in Chapters 2 and 3 by reviewing the existing literature on youthful disaffection, how it is to be understood and what the ‘causes’ of such disaffection appear to be. In Chapter 4 we consider briefly the history of mentoring and the research evidence, limited though it is, on the impact of such interventions. Chapters 5–9 then explore the nature and impact of mentoring, looking at mentors’ and young people’s experiences of the programme and assessing its effect on the young people’s engagement with education, training and work, and on their offending and drug and alcohol use. What is the promise of mentoring and how realistic is it to believe that it can have a significant impact on youthful offending and disaffection more generally? Are there particular young people who are likely to benefit from mentoring and particular ways that this intervention can be most successfully delivered? These and related questions are explored in the concluding chapter and recommendations are made for future policy and practice in this area.

![]()

Chapter 2

Youth disaffection

Introduction

There is a vast literature, across a range of disciplines, concerned with the ‘problems’ of youth.1 Popular discussion frequently, and academic discussion on occasion, treats concerns about youth as if they were almost entirely without precedent – in nature or extent, or sometimes both. It is important to recognize, however, that complaint and concern about young people are far from new (Pearson 1983). While recognizing the considerable historical continuities which underpin much discussion of youth, it is also clear that there have been profound changes affecting young people in Britain over the past two decades. In particular, a considerable quantity of social science research has charted changing education and labour market experiences during this period.

Where once the majority of young people left full-time education at the end of compulsory schooling, now the majority stay on. Thus, for example, whereas in the early 1970s the vast majority of the two thirds of young people who left school at 15 (the then school leaving age) moved straight into employment, by the early 1990s the proportion moving into full-time employment was less than one fifth (Courtenay and McAleese 1993). At the heart of such changes was the rapid contraction of the youth labour market. In the 1980s youth unemployment increased rapidly and successive governments introduced a series of strategies intended to increase skills and qualification levels among young people (expanding further education and introducing training schemes) and to discourage non-participation (via, for example, the removal of state benefits for 16–17-year-olds in 1988).

Predictably enough, therefore, the transitions experienced by young people in Britain at the beginning of the twenty-first century have become considerably more complex. Where once the ‘transition from school to work’ was a primary focus, the emphasis is increasingly on the differentiation and elongation of multiple transitions. In particular, there has been a significant expansion of ‘traditional’ routes through academic education, the creation of new routes via vocational education, and the growth of a relatively new ‘destination’: temporary or permanent unemployment. Crucially, for many young people, the length of time taken to complete transitions to employment is now considerably extended.

It is not only the way young people experience the transition to work which has been affected by the restructuring of the adult labour market and the decline in the youth labour market. Additionally, the other key transitions faced by young people – the transition from family of origin to family of destination, and the transition from the parental home into independent living – have also been transformed (Coles 1995). The extension and differentiation of the transition into employment have complicated the domestic and housing transitions faced by young people. At its most positive this may be presented as an increased series of choices confronting contemporary youth – sometimes seen as characteristic of a process of ‘individualization’. It has also been characterized in the literature as an increase in the range of ‘risks’ faced by young people (Furlong and Cartmel 1997). Roberts (1995: 118) summarizes such an idea in the following way:

It is as if people nowadays embark on their life journeys without reliable maps, all in private motor cars rather than the trains and buses in which entire classes once travelled together … The ‘cars’ in which individuals now travel do not all have equally powerful engines. Some young people have already accumulated advantages in terms of economic assets and socio-cultural capital. Some have to travel by bicycle or on foot. But everyone has to take risks. No one can be certain where the roads that they can take will lead.

The outcome of all this, it is argued, is that young people are faced with a more uncertain world. Transitions towards employment, and by implication youthful (semi) dependence on adults, have been extended. For many young people such transitions are successfully negotiated and managed; for others, though, there are considerable hurdles to be overcome. For these or other reasons many young people experience a sense of being outside the mainstream; or being prevented in some way from participating; they become what are often referred to as ‘disaffected young people’. In this chapter we explore this idea of ‘disaffection’, what it is taken to mean, what research has to tell us about so-called disaffected young people, primarily, but not exclusively, between the ages of 13 and 19. We begin by considering the nature of school disaffection – including under-achievement, disruptive behaviour, truancy and exclusion – and then move on to consider young people not in education, employment or training (NEET) and other indications of disaffection such as drug (ab)use and youth crime. We examine the size of the particular populations concerned, look at recent trends, and at who truants, who is excluded from school and who is ‘not in education, employment or training’. Part of our concern is with transitions and trajectories; we examine the outcomes for young people who truant, are excluded from school and who are outside education, training and employment for different periods of time. Given the nature of the social backgrounds of the young people involved in the mentoring programmes that form the core of this book we pay particular regard to what is known about the experiences and outcomes for young people living in particularly poor neighbourhoods.

The meaning of disaffection

As Williamson and Middlemiss (1999: 13) note, discussion of ‘disaffected’ youth ‘is hampered by such a catch all phrase incorporating those who are temporarily sidetracked, the essentially confused and the deeply alienated’. It is hard not to agree with such a sentiment, particularly given the tricky nature of this and cognate terms such as ‘the underclass’. The arrival of the ‘New Labour’ government in May 1997 saw a significant increase in the emphasis placed on tackling what is currently referred to as ‘social exclusion’ (see Levitas 1998; Byrne 1999). Such exclusion and its impact on British society have been described in various ways: as the ‘thirty, thirty, forty society’ (Hutton 1996), the 90/10 Society (see Le Grand 1998) and, perhaps best known of all, in references to the emergence of a so-called British ‘underclass’ (Murray 1990). Each of these descriptions differs and each of them can be, and has been, challenged. However, what links them all is the perception that British society is increasingly socially polarized. There is a concern that the gap between the majority and an ‘excluded’ minority is growing. Such concerns are longstanding and have traditionally coalesced around the issue of poverty (Townsend 1979). The term ‘social exclusion’ broadens the focus from poverty to other forms of ‘participation’ in civil society. Thus, in addition to the very clear evidence that differences in income between the bottom 10 per cent and the rest have been widening (Joseph Rowntree Foundation 1995; Oppenheim and Harker 1996), evidence of the differential impact of other ‘harms’, such as crime, has also been taken as an indicator of exclusion (Hope 1996).

In the bulk of the literature on youth disaffection, or non-participation, there is a split focus on two groups (see, for example, Pearce and Hillman 1998). The first is those of compulsory school age who, for whatever, reason are absent from education or, while remaining in education, are significantly under-achieving or exhibiting disruptive behaviour. The second group are those who have passed the age of compulsory education and have neither continued in education nor are to be found in training or employment. We use this general organizing approach to structure our discussion of youth disaffection in this chapter.

Educational under-achievement

There have been major changes within education in the past two decades. Significantly more young people are staying on in full-time education for longer. Participation in higher education has expanded massively. Copious new forms of vocational education and new educational credentials have developed (and yet more are mooted). Alongside the increased emphasis on, and participation in, education there continues to be a significant group of young people who, at least as measured by formal qualifications, achieve little in school or thereafter. Thus, for example, approximately 5 per cent of boys and 4 per cent of girls have no GCSE passes at any grade at the age of 16 and approximately one quarter of all children aged 16 achieve no GCSE passes at grade A–C (DfES 2002).

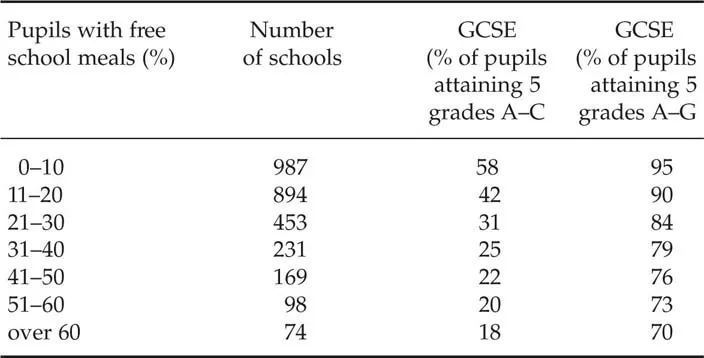

Despite the massive expansion in educational participation, research evidence points to the continued influence of social class differences in attainment. Analysis of the Youth Cohort Study (YCS) has found some narrowing of class differentials in high attainment, but has pointed to a solidifying of class differences among people with few or no qualifications (Payne 1995). Research would appear to indicate a significant school effect. However, even when this is particularly positive it may not be enough to overcome the combined effects of social disadvantage (Rutter et al. 1979). Gender differentials have changed in a similar way. Thus, although there has been a well publicized increase in relative achievement of girls over boys in relation to high grades and number of A–C GCSE passes, the proportions of girls and boys leaving education with few or no qualifications are not nearly so dissimilar. The association between poverty and deprivation in children’s families and in their neighbourhood and their performance in school is perhaps best illustrated by the analysis in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1 Poverty and school performance

Source: Glennerster (1998).

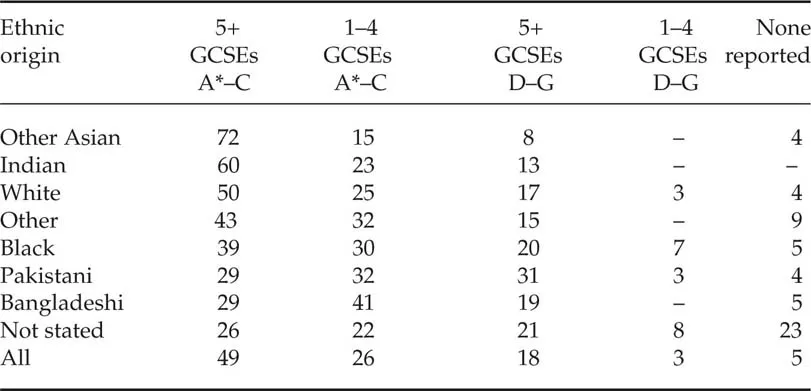

Data on ethnic differences in educational achievement are more difficult to come by. The first point to make, however, is that whatever pupils’ ethnic origin, those from the higher social class backgrounds do better on average (Gilborn and Gipps 1996). Research by the Policy Studies Institute (Hagell and Shaw 1996) found that ethnic minority pupils tended to have lower attainment levels than whites (Courtenay and McAleese 1993). In the PSI study, however, ‘Black other’ and ‘Black Caribbean’ pupils had the lowest average attainment scores, whereas Indian and Chinese pupils had the highest. According to Gilborn and Gipps (1996) those at greatest ‘risk’ are Caribbean young men, for it is they who achieve the equivalent of a higher grade (A–C) pass less frequently than the other groups (the differences are very small for girls). Analysis of the Youth Cohort Survey (DfES 2001) suggests that there are significant differences in achievement at GCSEs by ethnic origin (see Table 2.2).

Table 2.2 Attainment at GCSE level at the end of Year 11 by ethnic background (2000) (per cent of each ethnic group)

Source: DfES (2001).

Focusing more directly on the most ‘vulnerable’ there are some very stark messages in the research. According to a study by Barnardos (1996), three quarters of children looked after by local authorities leave school without any formal qualifications (compared with 8 per cent of the population overall) and only 12 per cent continue in further education after the end of compulsory schooling (Barnardos 1996). Few gain qualifications thereafter. The Barnardos picture is supported by other studies. Two studies by Stein (1983 1986) found the majority of young people leaving care to have no qualifications (the proportions without qualifications being 90 per cent and 54 per cent respectively). A further study of 16–19-year-old care leavers found that two thirds had no qualifications, that only 15 per cent had an A–C grade GCSE and, of a total sample of 183, only one respondent had an A level (Biehal et al. 1995). In 2000, the Department of Health published statistics on the educational qualifications of care leavers for the first time. These suggested that 70 per cent left care without any GCSE or GNVQ passes (DOH 2000).

Research on ‘looked after’ young people identifies a number of factors associated with the extremely poor levels of attainment among this population:

• Damaging pre-care experiences.

• Non-attendance at school.

• Emotional stress experienced prior to and during care.

• Inadequate liaison between carers and schools.

• Low expectations of carers and teachers.

• Prioritization of welfare above educational concerns.

• Disruption caused by placement moves and the low priority given to education when moves are being arranged (Stein and Carey 1986; Jackson 1988).

There may al...