Energy Performance of Residential Buildings

A Practical Guide for Energy Rating and Efficiency

- 150 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Energy Performance of Residential Buildings

A Practical Guide for Energy Rating and Efficiency

About this book

Energy Rating is a crucial consideration in modern building design, affirmed by the new EC Directive on the energy performance of buildings. Energy represents a high percentage of the running costs of a building, and has a significant impact on the comfort of the occupants. This book represents detailed information on energy rating of residential buildings, covering:

* Theoretical and experimental energy rating techniques: reviewing the state of the art and offering guidance on the in situ identification of the UA and gA values of buildings.

* New experimental protocols to evaluate energy performance: detailing a flexible new approach based on actual energy consumption. Data are collected using the Billed Energy Protocol (BEP) and Monitored Energy Protocol (MEP)

* Energy Normalization techniques: describing established methods plus a new Climate Severity Index, which offers significant benefits to the user.

Also included in this book are audit forms and a CD-ROM for applying the new rating methodology. The software, prepared in Excel, is easy to use, can be widely applied using both deterministic and experimental methods, and can be adapted to national peculiarities and energy policy criteria.

Energy Performance of Residential Buildings offers full and clear treatment of the key issues and will be an invaluable source of information for energy experts, building engineers, architects, physicists, project managers and local authorities.

The book stems from the EC-funded SAVE project entitled EUROCLASS. Participating institutes included:

* University of Athens, Greece

* Belgium Building Research Institute, Belgium

* University of Seville, Spain

* Royal Institute of Technology, Sweden

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

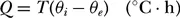

- The first part presents the result of the bibliographic study on the state of the art of the theoretical and experimental techniques used to determine the energy consumption of residential buildings.

- The second part deals with the in situ identification of the transmission heat loss coefficient + (UA value) and the gA values (characterizing the solar gains) of buildings.

- Much information can be found here about the calculation methods used to determine the energy consumption of the buildings.

- Some of these calculation methods are firmly based on experimental data. It should be noted that very often the articles focus more on the description of the calculation method than on the way of realizing the experimental monitoring.

- In general, few papers focus on the experimental techniques used to collect the data on site.

- Some of the experimental techniques described in the literature are quite old (some of them were developed more than 20 years ago). These experimental techniques do not take into account the latest developments in measuring techniques (for instance, the use of the Internet) and are therefore less interesting within the context of this project.

- the university projects and the Energy Barometer

- the Save HELP method

- short-term energy monitoring and primary and secondary term renormalization

- neural networks

- other related methods.

- Energy bills were collected before and after the retrofitting was carried out.

- Bill values were normalized according to temperature variations over the years.

- The energy saved was measured in corresponding litres of oil, during a reference year.

Fuel (unit) | Conversion factor |

Oil (m3) | 1.000 |

Gas (m3) | 0.471 |

Electricity (kWh) | 0.101 |

District heating (kWh) | 0.101 |

Energy (kWh) | Single-family house | Multi-family house |

Electrical appliances | 4,600 | 2,800 |

Hot water | 4,000 | 3,500 |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface: Introduction on the Energy Rating of Buildings

- Chapter 1. Review of selected theoretical and experimental techniques for energy characterization of buildings

- Chapter 2. Experimental methods for the energy characterization of buildings

- Chapter 3. Energy normalization techniques

- Chapter 4. The Euroclass method – description of the software

- Chapter 5. Examples and case studies

- Appendix 1: Audit form

- Appendix 2: Energy transmittance by glazing and shading factors

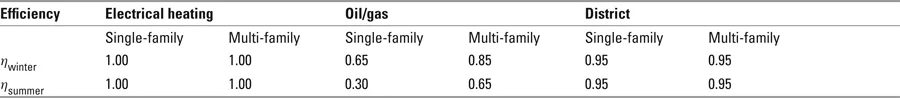

- Appendix 3: Estimated average fuel combustion efficiency of common heating appliances

- Index