![]()

Chapter

1

Catastrophes: An Overview of Family Reactions

CHARLES R. FIGLEY

The double doors of Community Hospital's emergency entrance swung open and Jose and Mary Allen rushed inside. Minutes ago they were phoned by the City Police Department and were informed that their 23-year-old daughter, Maria, had survived a head-on collision with another car. Maria's husband, Carl, who was driving her to the airport, was killed, along with the driver of the other car, which suddenly veered into their lane head-on. Jose and Mary went directly to the reception desk to ask how and when they would see their daughter; what was her condition? Mary was usually the calmer of the two but found herself screaming at the receptionist who wanted to know about insurance companies and home addresses. Those initial minutes in the emergency waiting room seemed like hours and the hours like days. Soon, though, they were joined by their two other daughters and several friends as the emergency medical team worked to save Maria's life. Just a week ago most of these same people had helped Jose and Mary celebrate their silver wedding anniversary. Everyone was so happy then. It seemed so long ago now.

They waited three hours before receiving word that Maria would survive and would probably recover fully over the next several months. As they waited, there were several more emergency arrivals; an assault, an industrial accident, and a near-drowning were the worst of them. Each victim was accompanied by worried family and friends. The Aliens were not alone that night.

After more than a month Maria was released from the hospital to complete her convalescence at her parent's home. Not only did her family worry about Maria's physical condition, but they also worried about her emotional condition. During her recovery she would experience a collection of symptoms which would be clinically diagnosed as "Post-traumatic Stress Disorder" (APA, 1980). This is a common reaction among the victims of a wide variety of catastrophic events which are emotionally upsetting. Maria's symptoms included, for example, painful recollections of the accident and initial experiences in the hospital; problems sleeping; moodiness; emotional withdrawal; jumpiness; crying spells; and varying amounts of depression associated with surviving when Carl did not. During this recuperative period Maria's family would be a key factor in her recovery from the emotional wounds of the accident as well as the physical ones. Along the way she would discover, much to her chagrin, that she was not the only one recovering from the emotional wake of this catastrophe; so was her family.

The story of the Allen family will unfold throughout this chapter. The shock of the accident and the sudden and profound impact it had on the lives of the victims—Maria and her family—exemplify the major thesis of this chapter and those to follow: that the family is a critical support system to human beings during and following a traumatic event and that the system and its members are affected in addition to the victim, and sometimes to a greater degree. In order to lay the groundwork, this chapter will attempt to reach three objectives:

- 1) to define and discuss the significance of catastrophic events and their impact on human emotion and behavior;

- 2) to characterize the patterns of family reactions to catastrophic versus normative sources of stress; and

- 3) to characterize the functional versus the dysfunctional methods of families' coping with stress.

STRESS IS LIFE AND LIFE IS STRESS

The week prior to the accident, the Allen family celebrated an anniversary: Jose and Mary had been married 25 years. They were certainly years of pleasure and satisfaction, but they were also filled with anger, frustrations, disappointments, and several points of near breakup. The girls could recall the many marital squabbles lasting late into the night. But the youngest daughter, Ann, a senior in high school, reported that much of the tension was gone. Yet, there were other reasons now for her parents to be upset: Jose's job is pressure-packed since the housing market is way off and his income has dropped precipitously; Mary has returned to work as a nurse and is frustrated by the lack of time and energy to attend to household matters as she once did. Linda, the middle child and a sophomore in college, is forlorn over the recent breakup with Bob—they had planned to marry next year. Then there was the issue of the house: The parents wanted to sell it (it was too big for them now) and their children wanted them to keep it (the memories it held, they believed, were worth the extra expense). And, of course, Maria and her husband were very happy newlyweds, though they worried about keeping their jobs (the plant may close due to the economy).

No one can avoid the stress of life. Indeed, stress is not always negative; it is part of life. The complete absence of stress is as great a cause for concern as is too much. Stress is life and life is stress. What the Aliens were recalling the week of the anniversary were the normative and environmental stressors discussed in detail in Volume I. Many of these are quite predictable and part of the natural growth and development of the family and its members through the life course. Often at some point in our lives, however, the individual and family developmental "rhythm" and routine may be jolted by an event occurring unexpectedly, off "schedule." These events and the pile-up of other normative stressors can cause the family to experience a crisis, under certain conditions. However, a catastrophe requires immediate attention and is, thus, synonymous with crisis.

CATASTROPHIC LIFE EXPERIENCES

At any time, anywhere, and under any circumstance we may be confronted with a catastrophe. A catastrophe is an event which is sudden, unexpected, often life-threatening (to us or someone we care deeply about), and due to the circumstances renders the survivors feeling an extreme sense of helplessness. With sufficient magnitude the event will 1) disrupt the lifestyle and routine of the survivors; 2) cause a sense of destruction, disruption, and loss; along with 3) a permanent and detailed memory of the event which may be recalled voluntarily or involuntarily (Burgess & Baldwin, 1981; Figley, 1978, 1979, 1982; Horowitz, 1979).

Victim Reactions

Figley (1979, 1982) has discussed the immediate and long-term consequences of catastrophe, drawing parallels, for example, among the emotional experiences of those who have survived war combat, being a prisoner of war, being a hostage of terrorists, being raped, or being a victim of a natural disaster. A simple model may be useful here to discuss the long-term impact of catastrophes as background for considering the role and impact of these catastrophic experiences in family life.

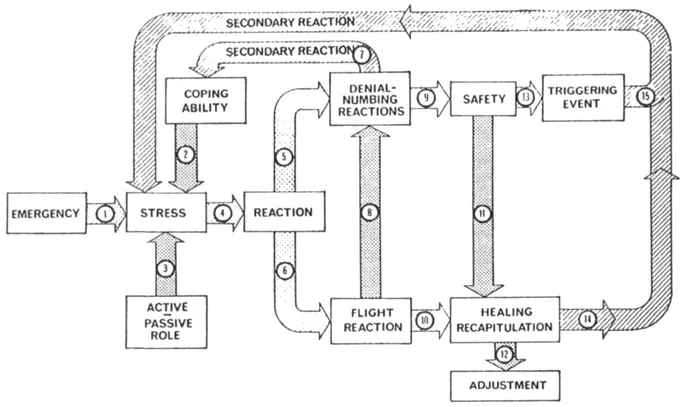

A Model of Catastrophic Experiences. There has been considerable speculation about how human beings behave in extreme emergency situations, such as passengers aboard a sinking ocean liner or disabled plane. How is it that some people stay calm, while others panic? What explains the sudden remembrances of a traumatic event which occurred a decade earlier, but which stimulates in the victim the same reactions as if it were happening again? Research reports have emerged over the last 40 years regarding, for example, soldiers in war (Figley, 1978; Grinker & Spiegel, 1945; Kalinowksy, 1950), flood victims (Bennet, 1970; Huerta & Horton, 1978), fire victims (Adler, 1943; Green, 1980), natural disaster victims (Chamberlain, 1980; Moore, 1958; Quarantelli & Dynes, 1977), terrorism (Ochberg, 1978), violence (Symonds, 1975), rape (Burgess & Holmstrom, 1979a and b; Katz & Mazur, 1979; Werner, 1972), and various other traumatic experiences (Horowitz, 1976; Janis, 1969; Lazarus, 1966). Except for Horowitz (1976, 1979), there is little discussion of both the lingering emotional impact of traumatic experiences and the induction of trauma during the event. The model presented below was developed for the purpose of illustration and discussion (see Figure 1). It helps us appreciate the immediate and long-term emotional consequences of a catastrophe for those who survive, as well as for the people who love and care for the survivor, particularly the family.

The diagram provides a schema of the interrelationship among 11 factors beginning with the catastrophic event and ending with emotional adjustment. In essence the model suggests a sequence of perceptions and reactions during and following a catastrophe. Catastrophic stress is not only a function of exposure to the catastrophe, but also a result of two additional factors. One is the coping ability the victim has prior to the event. Some researchers have found that previous experience with other catastrophes (especially similar ones), an internal locus of control, hardiness in adversity, and an ability to concentrate under pressure are coping mechanisms which reduce the amount of stress experienced during an emergency situation. Maria, for example, in the seconds surrounding the auto accident, was able to stay calm enough (rather than "freezing" in a helpless state) to both alert her husband to the oncoming car and help him direct the car away from its path.

Another set of factors which are associated with the amount of stress experienced by catastrophe victims during and just after a catastrophe includes several "situational parameters." These comprise sociality (the extent to which there was communication among fellow victims), ignominy (the degree to which the experience was degrading, humiliating, embarrassing), and a sense of helplessness (inability to influence or stop the situation, especially the danger). These three sets of factors—the catastrophic event or emergency, the victim's coping ability, and the situational context of the victim—account for the degree of intensity of the traumatic stress.

Figure 1. Long-term Stress Reactions

The victim's response during this acutely stressful time follows what Walter Cannon (1929), a pioneer stress researcher physiologist, identified as the "fight-or-flight" response. Subsequent research focusing on victims, cited above, tends to support this perspective. Caught in a catastrophic situation a small number of victims become panic-stricken and unable to function other than adopting a "flight reaction," except when fleeing (such as from a burning building) is the most appropriate response. Very frequently this reaction is accompanied by considerable emotional reactions on the part of the victim which attract the attention and assistance of others. This may result in (arrow 10) experiences of "healing recapitulation," whereby the victim is able to discuss his or her traumatic stress, after being removed from the catastrophe (such as a rape victim). Most often, however, during catastrophes which last over an extended period of time (war, captivity, blizzard), victims must somehow endure to cope with the continuing threat (arrows 5 through 8): to "fight" the catastrophe. This reaction, the "denial-numbing" response, was identified by Mardi Horowitz (1974, 1976) as a defensive coping mechanism that tends to remain with the victim long after the catastrophe ended. But as noted by others (Figley, 1978; Figley & Sprenkle, 1978), such a response is adaptable to surviving at the time. It is adaptable because the victim, caught in the catastrophe, either denies (or is incapable of perceiving) that the situation is as bad as it is or becomes numb to the stress (refusing to think about it). Both responses, the victim discovers, result in increased coping ability. The victim is becoming a "veteran" of the catastrophe, learning what it takes to survive—both in action and in thought. As a result there is a concomitant reduction in the amount of traumatic stress experienced during the catastrophe. This is why the initial period of any catastrophe is the most stressful and traumatic. Thus, during the period of the emergency (catastrophic event), the victim "circles" through a stress-reaction-denial/numbing-coping cycle to survive until the emergency is over.

The second facet of the model, the post-catastrophic (post-traumatic) period involves being physically away from the emergency, but not emotionally over it. Many catastrophe scholars have described this period as the "disillusionment phase" among disaster survivors (cf., Chapter 8), "disorganization and relapse" among rape victims (cf., Chapter 7) and periods of "relief and confusion, and avoidance" among combat veterans (cf., Chapter 9). It is within this period of "safety" (Horowitz, 1976) that victims are susceptible to powerful and painful recollections of the emergency (Figley, 1978, 1980b). Why? Based on research and clinical reports of thousands of victims of a wide variety of catastrophes, it is believed that victims attempt to cognitively master the impressions and memories of the catastrophe by answering such fundamental questions as:

- 1) What happened to me?

- 2) How did it happen?

- 3) Why me?

- 4) Why did I act as I did?

- 5) What will I do in another catastrophe?

When anything confronts us which is unexpected, we think about it enough until it becomes "expected" in the future.

Thus, following a catastrophe, victims ruminate about the series of events which entrapped them and search for these and other questions. As a result of their attempts to master the memories of the catastrophe, they may recall something that is especially troubling and so may trigger a secondary reaction (arrow 15) to the catastrophe. During this often brief episode victims may experience the same feelings and reactions which had occurred during the more troubling facets of the emergency. For Maria, for example, in an attempt to confront the questions above, she may suddenly recall those horror-filled seconds before the crash and become hysterical. During this episode, victims begin to cope much as they did during the emergency: experiencing the stress-reaction-denial/numbing-coping cycle. Victims may choose not to think about the events (i.e., denial-numbing) but may be "forced" to think about them by some situation, person, thing, or thought (i.e., triggering event) which startles victims into reminding them of the emergency. These have been referred to as flashbacks by several scholars and clinicians (cf., Figley, 1978).

The family has a central role to play at this point. Family members, perhaps more than any other group of people, can detect when the victim has not fully recovered emotionally from his or her ordeal (in contrast, for example, to clinicians, who are unable to distinguish between the victim's stress reactions and typical behavior). Moreover, the victim often feels more comfortable discussing his/her experience with family members. Thus, the family may be instrumental in promoting Healing Recapitulation (treating the "emotional wound" by extensive discussion) in order to help the victimized family member address and answer the questions of victims and reach Adjustment. Along the way, however, the victim (arrow 14) will experience several secondary reaction episodes.

It is important to recognize that with sufficient attention to the recovery process, the victim becomes a "survivor" (Figley, 1979). A survivor is able to take advantage of the skills developed as a result of his or her catastrophic experiences: the skills of survival; the confidence of mastering the stress during and following the catastrophe. A victim would say, for example, "I can't do it because of what I went through (during the catastrophe and its wake)!" In contrast, a survivor would say, "I can do it because of what I have survived!" This is consistent with research in experimental psychology in the area of learned helplessness (cf., Garber & Seligman, 1980), which suggests that animals and humans adapt by giving up, remaining a victim.

A Summary of the Victim's Response. According to the latest research on human response to extraordinary, sudden, and overwhelmingly stressful events, those caught in these catastrophes do not, as a rule, panic (Quarantelli & Dynes, 1977). Victims attempt to survive as best they can. The longer the ordeal, the greater the prospect of developing a strategy for survival, since the victim begins either to deny the direness of his or her situation or to become used to it. This survival behavior lasts beyond the length of the catastrophe, however, and over the months following the event the victim slowly regains his or her composure. The victim's initial and constant recollections of the event—and the accompanying hyper-alertness, sleeping problems, phobia, depression, and flashbacks—begin to fade. Usually, the more social support the victim receives during this period, providing him or her with an opportunity to talk...