eBook - ePub

Imagery

About this book

This advanced undergraduate textbook structures and integrates research on imagery under four headings: imagery as a personal or phenomenal experience; imagery as a mental representation; imagery as a property or attribute of materials; and imagery as a cognitive process that is under strategic control. A major part of the discussion under each of these headings concerns the ways in which the structures, mechanisms, and processes in the brain mediate our subjective experience of imagery and our observable behaviour when we make use of it in cognitive tasks.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction

Image…. A mental representation of something (esp. a visible object), not by direct perception, but by memory or imagination; a mental picture or impression; an idea, conception….

(Oxford English Dictionary)

This contribution to a modular textbook on Cognitive Psychology has to do with the concept of mental imagery. Investigations of mental imagery can be traced back over more than 2500 years, they were an important part of the earliest attempt to devise a scientific psychology in the 19th century, and they were at the forefront of the initial development of cognitive psychology in the 1960s. Since then, research on mental imagery has presented a challenge for mainstream cognitive psychology by generating new kinds of theory concerning potential mental representations and new methods for investigating those representations.

Conceptualising imagery

Research into imagery does not constitute a single homogeneous field, even within cognitive psychology, and it is all the more interesting as a result. However, this also makes it much more difficult for the outsider or the student to appreciate the different strands and how they hang together. I have found it helpful to classify research on imagery under four headings, and these provide the organising structure for the chapters in this book. One approach, perhaps the one that makes most sense to non-psychologists, is to focus upon imagery as a personal or phenomenal experience. A second approach, perhaps the one that makes most sense to other psychologists, is to focus on imagery as a mental or “internal” representation. A third approach, one which was represented in the earliest attempts to investigate imagery within cognitive psychology, is to focus upon imagery as a property or attribute of the materials that subjects have to deal with in laboratory experiments. The fourth approach, which figures prominently in recent research but originated in the earliest discourse concerning mental imagery, is to focus upon imagery as a process that is under strategic control.

Investigating imagery

Accordingly, in the chapters that follow, I shall try to present a coherent view of the relevant literature by dealing successively with these four ways of conceptualising imagery. Before doing so, however, I also need to explain that, within the paradigms and methods of cognitive psychology, imagery can be investigated in two different ways:

• as a dependent variable (in other words, as something that is measured by researchers), or

• as an independent variable (in other words, as something that is manipulated by researchers).

These two approaches are intrinsically complementary to each other, but they are inevitably associated with different kinds of research methodology.

Research in the first tradition has usually been concerned with the subjective and qualitative aspects of imagery (for example, its vividness or its controllability), and the extent to which mental images are structurally similar to the physical objects that are being imaged. These questions will be considered in Chapter 2. Research of this sort also considers the role of imagery as a strategy in remembering and in other cognitive tasks, and this issue will be discussed in Chapter 5. What is of interest under this heading is how the experience of imagery and the use of imagery vary from one person to another, from one task to another, or from one situation to another.

Research in the second tradition is, in many ways, more in keeping with the positivist, behaviourist, and experimentalist legacy that is still very much alive in contemporary cognitive psychology. Such research has usually been concerned with the objective, observable, and quantifiable aspects of cognition, which are reflected (it is hoped) in behaviour and especially in performance in remembering and other cognitive tasks. What is of interest under this heading is how observable performance is affected by variations in the abilities of the subjects, in the image-evoking properties of the experimental materials, and by the administration of instructions and other manipulations. These different questions will be discussed in Chapters 3, 4, and 5, respectively.

Imagery and the brain

Regardless of how imagery is investigated or conceptualised, all cognitive psychologists would nowadays agree that people’s ability to create, contemplate, and manipulate images depends upon the integrity of structures, mechanisms, and processes in our brains. It is therefore interesting and important to try to understand the ways in which these structures, mechanisms, and processes mediate our subjective experience and observable behaviour. This will be an important part of the discussion in each of the four main chapters in this book, and accordingly it will be useful to summarise the main anatomical features of the brain to which I shall refer during these discussions.

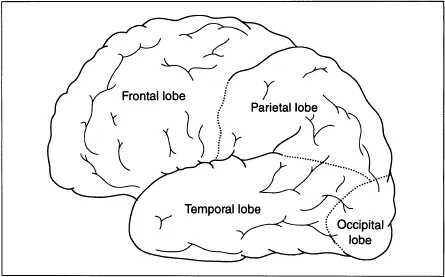

Figure 1.1 shows a simplified view of the left side of the human brain. The cerebrum consists of two hemispheres that are connected by the three cerebral commissures, of which the most important is the great commissure or corpus callosum. Each of the two hemispheres consists of an inner core of white matter, surrounded by a covering of grey matter (the cerebral cortex). The cortex of each cerebral hemisphere is described in terms of four regions: the frontal lobe, the temporal lobe, the parietal lobe, and the occipital lobe. Areas within each of these lobes are identified by reference to different directions:

• anterior (to the front) versus posterior (to the rear);

• superior (above) versus inferior (below).

In humans and other upright species, “anterior” means the same as “ventral” (literally, “towards the belly”), and “posterior” means the same as “dorsal” (literally, “towards the back”).

In this book, I shall consider three different kinds of evidence that help to elucidate the brain mechanisms involved in imagery. One kind of evidence is obtained by studying the behaviour of “normal” (i.e. intact) individuals. The classic contribution of what might be referred to as “experimental neuropsychology” has been the development of ideas about the representation of language in the human brain on the basis of procedures that permit the presentation of individual stimuli solely to one cerebral hemisphere. For example, it is well known that when pairs of stimuli are presented simultaneously to the left and the right halves of the visual field (or to the left and right ears), recognition of the stimulus presented to the right visual hemifield (or to the right ear) is better if the items in question are verbal. Conversely, the recognition of the stimulus presented to the left visual hemifield (or to the left ear) is better if the items in question are difficult to describe or label in purely verbal terms. Given that, under these experimental conditions, each visual hemifield and each ear enjoy privileged access to the opposite hemisphere of the brain, these results are generally taken to confirm the view that the left and right hemispheres have different roles in the processing of verbal and non-verbal information.

FIG. 1.1. Exterior view of the left side of the brain. From Brain Damage, Behaviour, and the Mind (p. 4), by M. Williams, 1979, Chichester, UK: Wiley. Copyright ©1979 by John Wiley & Sons Ltd. Reprinted with permission.

In practice, however, these experimental methods involving lateralised presentations provide only weak evidence concerning the neural representation of psychological functions in the two cerebral hemispheres. A second approach is to obtain “on-line” recording of brain activity whilst the individuals in question are performing specific experimental tasks. This traditionally involved the measurement of changes in the electrical potential of the brain using electrodes attached to the scalp. The sort of record that is produced is known as an electroencephalogram (EEG). Researchers are sometimes interested in the specific changes in electrical potential that are evoked by presentation of a particular stimulus, and these are known as event-related potentials (ERPs). EEG and the newer but closely related technique of magnetoencephalography (MEG), which measures the magnetic field generated by the brain’s electrical activity, provide a good account of changes over time, but the spatial views of the brain and its workings in cognitive tasks that are provided by these methods are relatively fuzzy and obscure.

The introduction of computerised tomography (CT) and especially magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provided views of the brain which were of much higher resolution but which were intrinsically static in nature. Studies of regional cerebral blood flow using positron emission tomography (PET) provide a better view of brain activity during ongoing cognitive tasks, but these are less adequate in terms of spatial resolution. Accordingly, the state of the art in brain imaging research is to link these two approaches, thus exploiting their respective strengths, and research laboratories and clinical facilities around the world are adopting MRI and PET technology to study activity within specific brain structures over the course of time. In principle, these techniques can be used with both intact individuals and neurological patients, but for research purposes the subjects are usually normal volunteers.

A third approach is that of clinical neuropsychology: in other words, the investigation of psychological functions and processes in patients who have suffered actual physical damage to the central nervous system. These patients fall into three main categories. First, there are cases that result from physical injury to the head. In wartime, traumatic damage is associated with open wounds that are produced by weapons or shrapnel. In peacetime, however, such damage more often takes the form of “closed” head injuries in which the contents of the skull are not exposed. Second, brain dysfunction is also associated with neurological diseases, especially those of a histopathological nature (such as cerebral tumours) and those involving the cerebrovascular system. Third, brain damage may also arise as the consequence of surgical treatment intended to alleviate the symptoms of neurological disease.

Under the latter heading, two groups will be of particular interest in this book. Patients in both groups have typically undergone surgical treatment to alleviate chronic, intractable epileptic conditions. One group consists of patients who have undergone surgical resection of (a portion of) a temporal lobe. Bilateral temporal lobectomy (removal of both temporal lobes) is known to give rise to a severe amnesic condition, and most patients will have undergone a unilateral temporal lobectomy. The second group contains patients in whom the hemispheres have been separated by sectioning of the corpus callosum and perhaps the optic chiasm and the other commissures, too. This surgical procedure is described clinically as a commissurotomy, but it is more colloquially known as the “split-brain” technique.

Is imagery a right-hemisphere function?

The findings of research into the effects of brain damage tend to fit well with the experimental data from normal individuals mentioned earlier with regard to the relative contributions of the two cerebral hemispheres to performance in linguistic and non-linguistic tasks. For example, patients who have lesions of the left temporal lobe are found to be impaired in tests of verbal memory but not in tests involving complex displays that cannot be readily described or labelled, such as unfamiliar human faces or abstract pictures. Conversely, patients who have lesions of the right temporal lobe are generally found to be impaired in the latter tests of non-verbal memory, but not in tests of verbal memory (see, for example, Milner, 1971).

Mental imagery can of course be used to represent verbally presented information, but it is not tied to a specific way of expressing that information. It can also be used to represent events and experiences that are difficult to label or describe. Hence, mental imagery appears to be an intrinsically non-verbal mode of thinking, and one might therefore anticipate that the neuroanatomical basis of mental imagery would be contained in the right cerebral hemisphere. In fact, this idea has quite a long history. Ley (1983) quoted the English neurologist Hughlings Jackson as writing over 100 years previously that “the posterior lobe on the right side [of the brain] … is the chief seat of the revival of images” (p. 252). Nowadays, the general idea that the right cerebral hemisphere is somehow specialised for mental imagery pervades a good deal of popular writing. Nevertheless, as Ehrlichman and Barrett (1983) pointed out, this idea needs to be evaluated critically and carefully against possible alternative hypotheses.

One assumption underlying this idea is certainly unlikely to stand this test. This is the idea that imagery is based upon a single mechanism that is localised within just one cerebral hemisphere. Kosslyn (1980) put forward the idea that imagery depends upon a complex system which consists of a large number of different components or subsystems. This idea is generally accepted, even though researchers may disagree over what these components actually are. Consequently, it is the localisation of these different components within the brain (and especially their lateralisation between the two hemispheres) that needs to be addressed by neuropsychological research, and, accordingly, this will be a key theme in each of the chapters in this book.

Summary: Introduction

1. Researchers have conceptualised mental imagery in different ways: as a phenomenal experience, as an internal representation, as a stimulus attribute, and as a cognitive strategy.

2. Imagery can be investigated either as a dependent variable or as an independent variable. The two approaches are complementary but involve different kinds of research methodology.

3. Imagery depends on the integrity of structures in the brain. These can be investigated by using the methods of experimental neuropsychology, by using physiological recording and brain-mapping methods, and by studying the effects of brain damage.

4. It is widely assumed that imagery is based upon a single mechanism that is localised in the right cerebral hemisphere. This idea that imagery is a right-hemisphere function needs to be critically examined. The idea that imagery is based upon a unitary mechanism is certainly open to question.

2

Imagery as a phenomenal experience

Mental imagery is essentially a “private” or “subjective” experience, in the sense that we cannot directly observe other people’s mental images. This is equally true of other mental events, such as sensations, thoughts, and feelings. Instead, we get to know about other people’s mental states on the basis of what they say and what they do. Sometimes, as in the case of pain or happiness, for instance, there is a characteristic way that a mental state is displayed in a person’s behaviour: we can tell that somebody has toothache from the way that they hold their jaw and moan. Equally, however, we can tell that somebody has toothache because they say, “I’ve got toothache” (Wittgenstein, 1958, p. 24). In both cases, of course, they might just be pretending to have toothache, but this does not detract from the fact that we normally do come to know about other people’s mental experience on the basis of their verbal and non-verbal behaviour.

In the case of some mental events, however, there does not appear to be any characteristic behaviour of this sort, and this seems to be true, in particular, of mental imagery. As Quinton (1973, p....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Series Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Cover illustration

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Imagery as a phenomenal experience

- 3. Imagery as an internal representation

- 4. Imagery as a stimulus attribute

- 5. Imagery as a mnemonic strategy

- 6. Conclusions

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Imagery by Dr J Richardson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.