![]()

1

Getting Started

INTRODUCTION TO LEAN

Since the term “Lean” was first used by a team of MIT researchers studying the Toyota Production System, Lean principles and techniques have spread across the globe. An Internet search will generate many definitions and descriptions, such as “Lean means creating more value for customers with fewer resources.”1 It’s more than a set of tools and techniques to identify and eliminate waste—it’s an operating principle for smooth flow and standard work. Most importantly, it’s a perspective—a way of thinking. It’s not an acronym; it’s just a word. The “L” is not always capitalized. It’s not copyrighted; there’s no patent on Lean methodology—the field is wide open for growth and innovation.

My preferred definition comes from a paper produced by the Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA). I like it because it expresses the multidimensional aspect: “Lean is an organizational performance management system characterized by a collaborative approach between employees and managers to identify and minimize or eliminate activities that do not create value for the customers of a business process, or stakeholders.”2

The approach to continuous improvement in manufacturing has been adapted to finance, health care, and government. When Lean entered the public-sector decades after its proven effectiveness in manufacturing, its core concepts remained the same, with the same transformative potential as in private industry. However, the challenges differ due to various manifestations of muda, mura, and muri. Lean practitioners are most familiar with the Japanese term muda (waste), and perhaps less so with mura (unevenness, variation) and muri (overburden). Muri is a significant factor impeding Lean implementation in the public sector, and therein lies a tale.

STARTING THE JOURNEY

Fledging Lean efforts generally start with process mapping, and our start was no different. Here’s the story:

Shortly after his appointment to lead New Hampshire’s Department of Environmental Services (DES) in November 2006, Tom Burack became the chair of the Commissioners’ Group. Tom and a core group of other commissioners were using a collaborative leadership model to move beyond the individual fiefdoms to an era where they could operate as a single enterprise to serve the citizens of the state.

The first initiative was directed at customer service training (2007), which naturally lead to Lean process improvement (2008), given Lean’s focus on value for the customer. The following sentence was inserted into the list of job accountabilities for every job description in State service: “Recognizing that everyone we come in contact with is a customer; consistently treating all with courtesy, respect and professionalism; striving to exceed customer service expectations; and maintaining harmonious work relationships”.

The Commissioners’ Group heard about Lean’s potential in a presentation by then-state representative David Borden. Prior to his service in the NH legislature, David used Lean principles in the hospitality industry. He described his philosophy in his book, Perfect Service:

David worked with Commissioner John Barthelmes of the Department of Safety (DOS) and DOS Chief of Policy & Planning Kevin O’Brien to respond to customer complaints in the Division of Motor Vehicles substation in Manchester by organizing the first Lean event in a state agency.

David recalled how bad things were prior to the Lean initiative: “The DMV substation in Manchester had requested a state trooper to maintain order among frustrated driver’s license and automobile registration customers. Often people had to wait 2 hours only to be told that they had the wrong paperwork. ‘Don’t worry deary,’ the beleaguered clerk would say, ‘when you get back just come to the front of the line and I will handle it’… Kindly service, horrible process. Now the staff, with the help of two highly placed Department of Safety employees, have totally redesigned the processes and the state trooper is back at his day job. The lines have disappeared and one of the staff was not replaced when she retired.”

Improvements included cross-training of employees between registration and licensing. Customer wait times were reduced, and the frustration of waiting in the wrong line was eliminated as counter clerks were prepared to assist customers with either transaction. The customer feedback approval rating for the DMV went from 35% to 95%.

Confident of its potential, the Commissioners’ Group was eager to move forward with Lean. Fortuitously, DES received an Innovation Grant from the EPA, and Tom asked the State Bureau of Education & Training (BET) to arrange Lean training. BET Director Dennis Martino recruited Sam McKeeman, a trainer whose Lean work for Maine’s Department of Transportation had resulted in $310,000 of savings in the first year of the program. Tom invited his colleagues from other departments, including Transportation (DOT), Safety (DOS), Administrative Services (DAS) and Health & Human Services (DHHS) to attend Sam’s training, and to bring selected staff members.

The first class in Lean Process Improvement Techniques included several of us who would soon become a cadre of Lean activists. Sam introduced us to process mapping and we immediately saw the potential as several projects unfolded over the 5-day session. The DES project on issuing administrative orders (AO) was particularly promising. The future state workflow would reduce the process time for AOs from 18 steps to seven steps, changing the process from 114 days to 14 days. Another project reduced a permitting process from 16 steps to 5 steps.

Our multi-agency group of participants was eager to begin cutting the red tape that plagued our working lives. We were bitten by the Lean bug. Although we knew that overarching improvements would require legislative action or permission from risk-averse administrators, it was an incredibly empowering experience to see that we could make a start.

Commissioner Barthelmes (DOS) sent two staff members to attend the training: Roberta Witham, a statistical analyst, and Christopher Wagner of the NH State Police. The duo had not met prior to Lean training, but they were both chosen to lead the effort at DOS. Roberta recalled the Commissioner saying, “This is the way we are going to revolutionize Safety: learn and make process improvement happen.” After the training session, she and Chris had a brief “crap—what do we do now?” moment, but quickly adapted to their new mission. They established a pragmatic working model for Lean at the DOS; clearly the Commissioner had made the right call by selecting them to lead the initiative.

Roberta saw the need to do short kaizen events with tangible results. She joked that people knew they would retire before the seemingly never-ending efforts to redo the state’s aging IT system could be accomplished. Chris agreed that they should start with small, significant wins, noting that “we’re not trying to solve world hunger.” Taking a pragmatic approach, they targeted processes that could be improved by 80%, understanding that they could go back to the other 20% another time (Sam had recommended an 18-month interval for revisiting projects.)

Armed with rolls of brown paper, colorful sticky notes, and a can-do attitude, the new Lean practitioners put the lessons to work. They tackled one of the most onerous processes in New Hampshire State government: the preparation of contracts for review by the Governor and Executive Council (G&C). An examination of the current state found that more than 70% of the contracts prepared by Department of Safety were returned for rework. The Lean project identified several points of failure. For example, some of the reviewers would only read far enough to find one error, so the documents were returned with one item fixed, only to be sent back again as additional errors were subsequently identified. The team identified training needs and established standard work. After project was implemented, 92% of the documents were accepted on the first submission (Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1

Roberta Witham and Christopher Wagner present the results of their G&C project to a Lean class (2009).

With continued support from the Commissioner and Chief O’Brien, Chris and Roberta conducted a series of Lean projects. They developed a model for Lean teams to work of 4 half-days, followed by the presentation to the sponsor (“the sell”), which would take place early in the following week. While some of the team’s recommendations might be approved at the sell, the sponsor would have two weeks to respond to the entire package.

Early successes included reducing the amount of returned mail to the DMV from 18% to 2% (It was not possible to move away from mailing altogether due to a post 9/11 requirement to mail the applicant’s driver’s license to the home address on record.) In addition to the staff time spent on the project to design the future state and conduct training on the new workflow, the DOS spent $2,500 on software for address confirmation, resulting in a $225,000 saving in postage costs.

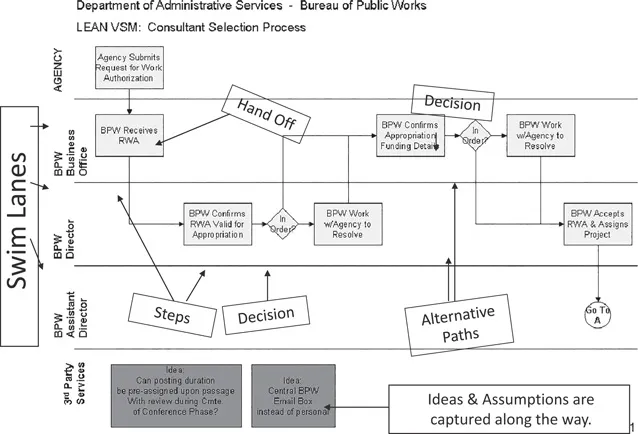

Department of Administrative Services (DAS) Commissioner Linda Hodgdon encouraged Lean training with real workplace projects for several work units within DAS. The Public Works unit mapped their consultant selection process using swim lanes (as depicted in the graphic that follows). By reducing the interdepartmental handoffs and other muda, their process went from 36 steps to 15 steps. A process that had taken 6–9 months was reduced to save 80 days per project—in many cases, they saved a construction season (Figure 1.2).

FIGURE 1.2

DAS project on the consultant selection process.

DHHS Commissioner Nick Toumpas supported a hub of Lean activity generated in the Office of Integrity and Improvement led by Linda Paquette and subsequently by John MacPhee. Lean efforts at DHHS took on a larger, long-range approach for several significant projects. Rather than the quick-hit style kaizen event used at DOS for 4 half-days, DHHS Lean practitioners attempted to get to the root cause of some of the most vexing processes. Two of these projects began during training sessions, but were too complex to be completed in the 5-day session with Sam: contracting and rule-making. The projects each took more than a year, with small wins along the way, and a larger win at the close.

In 2014, John unrolled the current state value stream map of the contracting process at a meeting of the Governor and Executive Council. Following that meeting, the council agreed to increase the threshold amount of the contracts required to be sent to them for review from $10,000 to $25,000.

An early attempt to lean the rule-making process took even longer than the contracting project. The project was championed by Representative David Borden, who had worked with Chief O’Brien on the project at the Manchester DMV office. In 2009, David recruited six of his fellow legislators to attend one of Sam’s training sessions. During the hands-on portion of the training, the legislators worked with a staff member from Legislative Services to map the rule-making process. It was a particularly challenging project: rules are drafted by staff in the dozens of departments within the Executive Branch, then subject to review by staff attorneys in Legislative Services, as well as a public comment period, before receiving final approval by the Joint Legislative Committee on Administrative Rules (JLCAR). Despite many snags along the way, the project resulted in the passage of legislation that reformed several aspects of the cumbersome process.

Below are excerpts from the data sheet used in that initial session. Sam introduced us to the types of measures used in manufacturing, including “up time,” “change over time,” and “first pass yield.” There’s a simplified version of the data sheet in the next chapter, which we adapted for our administrative processes. It was, however, useful to learn about Lean through a manufacturing lens. The “first pass yield” indicator reported ...