![]()

1

______

Assessing and

Improving Speaking

Speaking Goals

According to a report from the Office for Standards in Education (2008), children studying foreign languages have poor speaking skills despite improvements in the quality of teaching and learning. At all levels, the report found that speaking was the least developed of pupils’ skills and that pupils’ inability to express themselves had a negative impact on their confidence and enthusiasm. Students who have an A grade in language classes often cannot communicate in the language. Students who take a language class often complain to their friends or family members that they cannot speak the language. Bailey (2005) reports that speaking intuitively seems to be the most important of language skills because people who know a language are referred to as a “speaker” of the language as though speaking included all other skills.

The American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Language (ACTFL) promotes language skills in the United States. In 1996, a collaboration of four national language associations including ACTFL, American Association of Teachers of French (AATF), American Association of Teachers of German (AATG), and American Association of Teachers of Spanish (AATSP) developed five major goals of language study: Communication, Cultures, Connections, Comparisons, and Communities (1998). These goals interweave so that any one goal incorporates parts of the other goals. In the Communication goal, there are three standards and three modes.

♦“Standard 1.1: Students engage in conversations, provide and obtain information, express feelings and emotions, and exchange opinions” (interpersonal mode).

♦“Standard 1.2: Students understand and interpret written and spoken language on a variety of topics” (interpretative mode).

♦“Standard 1.3: Students present information, concepts, and ideas to an audience of listeners or readers on a variety of topics” (presentational mode). (Communication, Cultures, Connections, Comparisons, and Communities, 1998)

This book of speaking strategies focuses mainly on assessing an individual as he/she speaks.

Language learning has been transformed from learning about a language to actually speaking a language. ACTFL has moved from seat-time guidelines to proficiency-based guidelines. The ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines of 1999 establishes what it means to be proficient at the Superior, Advanced, Intermediate, and Novice levels (Breiner-Sanders, Lowe, Miles & Swender, 2000):

Superior-level speakers are characterized by the ability to:

♦Communicate with accuracy and fluency to participate fully and effectively in conversations on a variety of topics in formal and informal settings from both concrete and abstract perspectives. They can just as easily talk about their meal as a social or political issue. They satisfy the linguistic demands of professional and/or scholarly life.

♦Explain matters in detail, providing lengthy and coherent narrations, all with ease, fluency, and accuracy. They explain their opinions and construct and develop hypotheses to explore alternative possibilities.

♦Command a variety of interactive and discourse strategies such as turn-taking and separating main ideas from supporting ones through the use of syntactic and lexical devices, as well as intonational features such as pitch, stress, and tone.

Advanced-level speakers are characterized by the ability to:

♦Perform with linguistic ease, confidence, and competence. They discuss topics concretely and abstractly. They participate actively in formal exchanges on a variety of concrete topics such as work, school, home, leisure activities, as well as events of current, public, and personal interest or relevance.

♦Narrate and describe in major time frames with good control of aspect.

♦Provide a structured argument to explain and defend opinions and develop effective hypotheses within extended discourse.

♦Use communication strategies such as paraphrasing, circumlocution, and illustration.

♦Use precise vocabulary and intonation.

Intermediate-level speakers are characterized by the ability to:

♦Converse with ease and confidence when dealing with the most routine tasks and social situations. Handle many uncomplicated tasks and social situations requiring an exchange of basic information related to work, school, recreation, particular interests, self, family, home, and daily activities, as well as physical and social needs such as food, shopping, travel, and lodging.

♦Narrate and describe in major time frames using connected discourse of paragraph length; however, they cannot maintain the narration and demonstrate weaknesses in their narration.

♦Obtain and give information by asking and answering questions to obtain simple information to satisfy basic needs.

Novice-level speakers are characterized by the ability to:

♦Handle uncomplicated communicative tasks in straightforward social situations. They respond to simple questions on the predictable topics necessary for survival in the target language culture such as basic personal information, basic objectives, and a limited number of preferences or requests for information.

♦Convey minimal meaning by using isolated words and short, sometimes incomplete sentences. They use lists of words, memorized phrases and some personalized combinations of words and phrases.

♦Ask only a few formulaic questions. (Breiner-Sanders, Lowe, Miles & Swender, 2000)

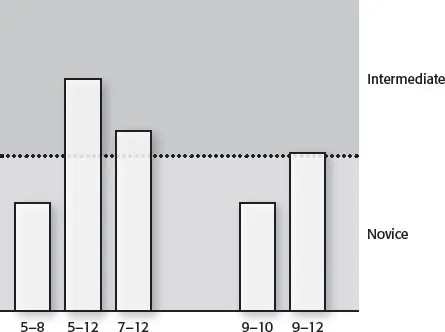

ACTFL has determined that by the end of the students’ first year of language learning, such as ninth grade or the combination of seventh and eighth grade, they can reach the middle of the Novice level (Figure 1.1, page 6). As they continue their second and third year of language study, they may reach the Intermediate level. Some students who take Advanced Placement or the equivalent begin to reach the lower levels of the Advanced (1998).

Speaking Assessments

Due to the increased emphasis on speaking, many language tests incorporate a speaking component. ACTFL's Oral Proficiency Interview, Center for Applied Linguistics’ Simulated Oral Proficiency Interview, ACTFL's Integrated Performance Assessment, the Advanced Placement test, and school district language finals represent a few assessments that include speaking a target language. In each speaking assessment, students perform an oral task and receive a level or a score. To illustrate, a student may respond with four sentences to a prompt situation such as agreeing with his friend (the teacher) on what they are going to do together this weekend. He may receive a score such as 4/6.

FIGURE 1.1 ACTFL Levels and Grade Levels

These oral assessments are final or summative assessments. These tests inform the students where they are in general terms with a final score or rating such as a “5” on the Advanced Placement exam. These tests do not help the students understand their specific strengths and areas for improvement. More importantly, they do not provide the students with strategies to become better speakers. Furthermore, the students take these speaking tests separately from classroom learning. These summative speaking assessments are not a natural part of the class. Additionally, the students take the same speaking assessment only once. They do not learn new strategies and then retake the assessment to show their growth over time. Finally, these one-time speaking assessments are high-stakes tests which create a great deal of student anxiety (Tuttle, 2009). Formative assessment overcomes these negatives of summative speaking tests.

You, along with your language colleagues, may have developed your own variations of assessments to test students’ speaking with your own rubrics or check lists. Buttner (2007) includes numerous ways in which she and others assess speaking such as “Essential Questions” and “Dialogue and Role Play Rubric.” These rubrics identify where the students are in the speaking process. Assessment tools need to identify specific speaking skills, not just a general skill category like “Completeness of response” and its vague four-point scale (Figure 1.2). For example, in a formative assessment rubric the general category of “Completeness of response” includes specific critical sub-skills and the teacher writes in a specific strategy to help the student improve (Figure 1.3, page 8).

FIGURE 1.2 Vague Summative Speaking Rubric (Partial)

| 4: Above Proficient | 3: Proficient | 2: Developing | 1: Beginning |

| Completeness of Response | Extremely complete | Generally complete | Sometimes complete | Incomplete |

If you use speaking rubrics that do not offer improvement strategies to the students, then the assessments remain summative. Formative assessment rubrics not only indicate the students’ strengths and areas for improvement, but also provide a concrete strategy to move the students forward in their speaking skills. If you do not offer the students any strategy for their improvement, they remain stuck in their present learning gaps and they are unlikely to show improvement from one assessment to the next. If coaches do not provide any strategies for improvement for their athletes during the season, their teams will not get better. If a person uses the wrong fingering for a piano piece for many hours, the person does not become a better musician.

Formative assessment embeds the oral evaluation into the normal classroom activities. These evaluations do not take time away from normal instruction since they are a natural outgrowth of the instruction. Also, formative assessment encourages peer review so that the whole class can be working in pairs to assess each other. Students have more opportunities to talk for extended periods of time with these formative assessments. When students evaluate each other in specific objective ways, such as determining if the partner gives information and opinions about a topic, they provide very good growth feedback to their partners. Growth happens when speaking is assessed on a frequent basis through formative assessment.

Although you may not formally assess often, you informally evaluate the oral proficiency of your students on a daily basis when you call on them in class. You react to their language successes and language problems as they occur. Omaggio Hadley (2001) reported several types of in-cl...