![]()

1

Pushing Beyond the Earth’s Limits

When historians look back on our times, the last half of the twentieth century will undoubtedly be labeled “the era of growth.” Take population. In 1950, there were 2.5 billion people in the world. By 2000, there were 6 billion. There has been more growth in world population since 1950 than during the preceding 4 million years.1

Recent growth in the world economy is even more remarkable. During the last half of the twentieth century, the world economy expanded sevenfold. Most striking of all, the growth in the world economy during the single year of 2000 exceeded that of the entire nineteenth century. Economic growth, now the goal of governments everywhere, has become the status quo. Stability is considered a departure from the norm.2

As the economy grows, its demands are outgrowing the earth, exceeding many of the planet’s natural capacities. While the world economy multiplied sevenfold in just 50 years, the earth’s natural life-support systems remained essentially the same. Water use tripled, but the capacity of the hydrological system to produce fresh water through evaporation changed little. The demand for seafood increased fivefold, but the sustainable yield of oceanic fisheries was unchanged. Fossil fuel burning raised carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions fourfold, but the capacity of nature to absorb CO2 changed little, leading to a buildup of CO2 in the atmosphere and a rise in the earth’s temperature. As human demands surpass the earth’s natural capacities, expanding food production becomes more difficult.3

Losing Agricultural Momentum

Environmentalists have been saying for years that if the environmental trends of recent decades continued the world would one day be in trouble. What was not clear was what form the trouble would take and when it would occur. It now seems likely to take the form of tightening food supplies, and within the next few years. Indeed, China’s forays into the world market in early 2004 to buy 8 million tons of wheat could mark the beginning of the global shift from an era of grain surpluses to one of grain scarcity.4

World grain production is a basic indicator of dietary adequacy at the individual level and of overall food security at the global level. After nearly tripling from 1950 to 1996, the grain harvest stayed flat for seven years in a row, through 2003, showing no increase at all. And in each of the last four of those years, production fell short of consumption. The shortfalls of nearly 100 million tons in 2002 and again in 2003 were the largest on record.5

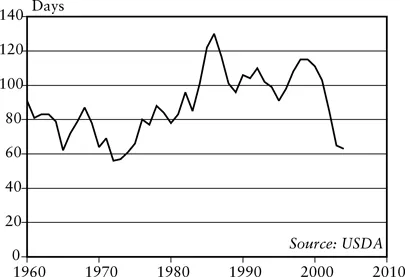

With consumption exceeding production for four years, world grain stocks dropped to the lowest level in 30 years. (See Figure 1–1.) The last time stocks were this low, in 1972–74, wheat and rice prices doubled. Importing countries competed vigorously for inadequate supplies. A politics of scarcity emerged—with some countries, such as the United States, restricting exports.6

Figure 1–1 World Grain Stocks as Days of Consumption, 1960–2004

In 2004 a combination of stronger grain prices at planting time and the best weather in a decade yielded a substantially larger harvest for the first time in eight years. Yet even with a harvest that was up 124 million tons from that in 2003, the world still consumed all the grain it produced, leaving none to rebuild stocks. If stocks cannot be rebuilt in a year of exceptional weather, when can they?7

From 1950 to 1984 world grain production expanded faster than population, raising the grain produced per person from 250 kilograms to the historical peak of 339 kilograms, an increase of 34 percent. This positive development initially reflected recovery from the disruption of World War II, and then later solid technological advances. The rising tide of food production lifted all ships, largely eradicating hunger in some countries and substantially reducing it in many others.8

Since 1984, however, grain harvest growth has fallen behind that of population, dropping the amount of grain produced per person to 308 kilograms in 2004, down 9 percent from its historic high point. Fortunately, part of the global decline was offset by the increasing efficiency with which feedgrains are converted into animal protein, thanks to the growing use of soybean meal as a protein supplement. Accordingly, the deterioration in nutrition has not been as great as the bare numbers would suggest.9

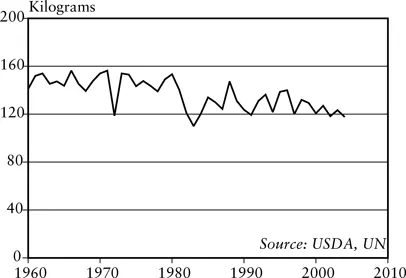

The one region where the decline in grain produced per person is unusually steep and where it is taking a heavy human toll is Africa. In addition to the nutrient depletion of soils and the steady shrinkage in grainland per person from population growth in recent decades, Africa must now contend with the loss of adults to AIDS, which is depleting the rural work force and undermining agriculture. From 1960 through 1981, grain production per person in sub-Saharan Africa ranged between 140 and 160 kilograms per person. (See Figure 1–2.) Then from 1980 through 2001 it fluctuated largely between 120 and 140 kilograms. And in two of the last three years, it has been below 120 kilograms—dropping to a level that leaves millions of Africans on the edge of starvation.10

Figure 1–2 Grain Production Per Person in Sub-Saharan Africa, 1960–2004

Several long-standing environmental trends are contributing to the global loss of agricultural momentum. Among these are the cumulative effects of soil erosion on land productivity, the loss of cropland to desertification, and the accelerating conversion of cropland to nonfarm uses. All are taking a toll, although their relative roles vary among countries.

Now two newer environmental trends—falling water tables and rising temperatures—are slowing the growth in world food production, as described later in this chapter. (See also Chapters 6 and 7.) In addition, farmers are faced with a shrinking backlog of unused technology. The high-yielding varieties of wheat, rice, and corn that were developed a generation or so ago are now widely used in industrial and developing countries alike. They doubled and tripled yields, but there have not been any dramatic advances in the genetic yield potential of grains since then.11

The use of fertilizer, which removed nutrient constraints and helped the new high-yielding varieties realize their full genetic potential during the last half-century, has now plateaued or even declined slightly in key food-producing countries. Among these are the United States, countries in Western Europe, Japan, and now possibly China as well. Meanwhile, the rapid growth in irrigation that characterized much of the last half-century has also slowed. Indeed, in some countries the irrigated area is shrinking.12

The bottom line is that it is now more difficult for farmers to keep up with the growing demand for grain. The rise in world grainland productivity, which averaged over 2 percent a year from 1950 to 1990, fell to scarcely 1 percent a year from 1990 to 2000. This will likely drop further in the years immediately ahead.13

If the rise in land productivity continues to slow and if population continues to grow by 70 million or more per year, governments may begin to define national security in terms of food shortages, rising food prices, and the emerging politics of scarcity. Food insecurity may soon eclipse terrorism as the overriding concern of national governments.14

Growth: The Environmental Fallout

The world economy, as now structured, is making excessive demands on the earth. Evidence of this can be seen in collapsing fisheries, shrinking forests, expanding deserts, rising CO2 levels, eroding soils, rising temperatures, falling water tables, melting glaciers, deteriorating grasslands, rising seas, rivers that are running dry, and disappearing species.

Nearly all these environmentally destructive trends adversely affect the world food prospect. For example, even a modest rise of 1 degree Fahrenheit in temperature in mountainous regions can substantially increase rainfall and decrease snowfall. The result is more flooding during the rainy season and less snowmelt to feed rivers during the dry season, when farmers need irrigation water.15

Or consider the collapse of fisheries and the associated leveling off of the oceanic fish catch. During the last half-century the fivefold growth in the world fish catch that satisfied much of the growing demand for animal protein pushed oceanic fisheries to their limits and beyond. Now, in this new century, we cannot expect any growth at all in the catch. All future growth in animal protein supplies can only come from the land, putting even more pressure on the earth’s land and water resources.16

Farmers have long had to cope with the cumulative effects of soil erosion on land productivity, the loss of cropland to nonfarm uses, and the encroachment of deserts on cropland. Now they are also being battered by higher temperatures and crop-scorching heat waves. Likewise, farmers who once had assured supplies of irrigation water are now forced to abandon irrigation as aquifers are depleted and wells go dry. Collectively this array of environmental trends is making it even more difficult for farmers to feed adequately the 70 million people added to our ranks each year.17

Until recently, the economic effects of environmental trends, such as overfishing, overpumping, and overplowing, were largely local. Among the many examples are the collapse of the cod fishery off Newfoundland from overfishing that cost Canada 40,000 jobs, the halving of Saudi Arabia’s wheat harvest as a result of aquifer depletion, and the shrinking grain harvest of Kazakhstan as wind erosion claimed half of its cropland.18

Now, if world food supplies tighten, we may see the first global economic effect of environmentally destructive trends. Rising food prices could be the first economic indicator to signal serious trouble in the deteriorating relationship between the global economy and the earth’s ecosystem. The short-lived 20-percent rise in world grain prices in early 2004 may turn out to be a warning tremor before the quake.19

Two New Challenges

As world demand for food has tripled, so too has the use of water for irrigation. As a result, the world is incurring a vast water deficit. But because this deficit takes the form of aquifer overpumping and falling water tables, it is nearly invisible. Falling water levels are often not discovered until wells go dry.20

The world water deficit is historically recent. Only within the last half-century, with the advent of powerful diesel and electrically driven pumps, has the world had the pumping capacity to deplete aquifers. The worldwide spread of these pumps since the late 1960s and the drilling of millions of wells, mostly for irrigation, have in many cases pushed water withdrawal beyond the aquifer’s recharge from rainfall. As a result, water tables are now falling in countries that are home to more than half of the world’s people, including China, India, and the United States—the three largest grain producers.21

Groundwater levels are falling throughout the northern half of China. Under the North China Plain, they are dropping one to three meters (3–10 feet) a year. In India, they are falling in most states, including the Punjab, the country’s breadbasket. And in the United States, water levels are falling throughout the southern Great Plains and the Southwest. Overpumping creates a false sense of food security: it enables us to satisfy growing food needs today, but it almost guarantees a decline in food production tomorrow when the aquifer is depleted.22

With 1,000 tons of water required to produce 1 ton of grain, food security is closely tied to water security. Seventy percent of world water use is for irrigation, 20 percent is used by industry, and 10 percent is for residential purposes. As urban water use rises even as aquifers are being depleted, farmers are faced with a shrinking share of a shrinking water supply.23

At the same time that water tables are falling, temperatures are rising. As concern about climate change has intensified, scientists have begun to focus on the precise relationship between temperature and crop yields. Crop ecologists at the International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines and at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) have jointly concluded that with each 1-degree Celsius rise in temperature during the growing season, the yields of wheat, rice, and corn drop by 10 percent.24

Over the last three decades, the earth’s average temperature has climbed by nearly 0.7 degrees Celsius, with the four warmest years on record coming during the last six years. In 2002, record-high temperatures and drought shrank grain harvests in both India and the United States. In 2003, it was Europe that bore the brunt of the intense heat. The record-breaking August heat wave that claimed 35,000 lives in eight nations withered grain harvests in virtually every country from France in the west through the Ukraine in the east.25

Th...