eBook - ePub

An Introduction to International Relations Theory

Perspectives and Themes

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

An Introduction to International Relations Theory

Perspectives and Themes

About this book

This long-awaited new edition has been fully updated and revised by the original authors as well as two new members of the author team. Based on many years of active research and teaching it takes the discipline's most difficult aspects and makes them accessible and interesting.

Each chapter builds up an understanding of the different ways of looking at the world. The clarity of presentation allows students to rapidly develop a theoretical framework and to apply this knowledge widely as a way of understanding both more advanced theoretical texts and events in world politics.

Suitable for first and second year undergraduates studying international relations and international relations theory.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access An Introduction to International Relations Theory by Jill Steans,Lloyd Pettiford,Thomas Diez,Imad El-Anis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Liberalism

Introduction

Liberal thought about the nature of international relations has a long tradition dating back to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. During these centuries liberal philosophers and political thinkers debated the difficulties of establishing just, orderly and peaceful relations between peoples. One of the most systematic and thoughtful accounts of the problems of world peace was produced by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant in 1795 in an essay entitled Perpetual Peace. Kantian thought has been profoundly influential in the development of liberalism in IR (see below).

However, solutions to the problem of war evaded even the most eminent of thinkers. In the nineteenth century, scholars contented themselves with merely describing historical events, and the study of international affairs was largely confined to the field of diplomatic history. In the wake of the destruction of the First World War, there was a sense of greater urgency to discover the means of preventing conflict. The senseless waste of life which characterised this conflict brought about a new determination that reason and cooperation must prevail.

While the conflict itself was horrific, International Relations scholars were initially quite optimistic about the possibilities of ending the misery of war. A new generation of scholars was deeply interested in schemes which would promote cooperative relations among states and allow the realisation of a just and peaceful international order, such as the fledgling League of Nations (see World Example Box, pp. 33–4). This liberal or idealist enterprise rested on the beliefs that people in general are inherently good and have no interest in prosecuting wars with one another. Furthermore, people suffer greatly as a consequence of war and thus desire dialogue over belligerence. Therefore, for idealists all that was needed to end war was respect for the rule of law and stable institutions which could provide some form of international order conducive to peace and security. The widespread anti-war sentiment within Europe and North America which existed in the 1920s seemed to provide the necessary widespread public support for such an enterprise to succeed.

During the late 1930s and following the Second World War, idealism fell out of favour for a long period of time, as realism (chapter 2) seemed to provide a better account of the power politics characteristic of the post-war era. The decline in the popularity of idealism was partly encouraged by the failure of The League of Nations to act as a forum for resolving differences peacefully and as a mechanism to prevent inter-state conflict. With the outbreak of a number of major conflicts in the inter-war period, the onset of economic nationalism as a result of the Great Depression and World War Two, it is not entirely surprising that a much more pessimistic view of world politics prevailed from the 1940s onwards. However, idealism dominated the academic study of International Relations between the First and Second World Wars with its basic faith in the potential for good in human beings and in the promise of the rule of law, democracy and human rights and continues to be influential within liberal IR theory today.

Idealism as used here is about a particular approach to International Relations and should not be confused with the notion of ‘idealism’ as describing say an unrealistic person. Further explanation in text.

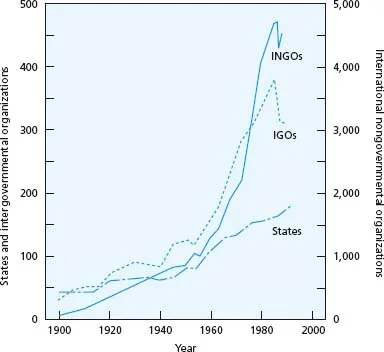

There have been many innovations in liberal theory since the 1970s which are reflected in a number of distinctive strands of thought within liberalism. For example, idealism, pluralism, interdependence theory, transnationalism, liberal internationalism, liberal peace theory, neo-liberal institutionalism and world society approaches. In the 1970s a liberal literature on transnational relations and world society developed. So called ‘liberal pluralists’ pointed to the growing importance of multinational corporations (MNCs), non-governmental organisations (NGOs), pressure groups, and intergovernmental organizations (IGOs), as evidence that states were no longer the only significant actors in international relations. Liberal pluralists believed that power, influence and agency in world politics were now exercised by a range of different types of actors.

Liberal internationalism: the belief that political activity should be framed in terms of a universal human condition rather than in relation to the particularities of any given nation.

Furthermore, by the 1980s conflict was not the major process in international relations as, increasingly, cooperation in pursuit of mutual interests was a prominent feature of world politics. Terms much in vogue in contemporary International Relations literature (and in the media), such as ‘globalisation’ or ‘multiculturalism’, while not intrinsically liberal, have liberal adherents or interpretations and have received growing attention from liberal scholars. In more recent years liberals have made important contributions to the study of international relations in the areas of international order, institutions and processes of governance, human rights, democratisation, peace and economic integration.

In this chapter we aim to highlight the many and varied ways in which liberal thought has contributed to International Relations. We present liberalism as a coherent perspective or school of thought. Our justification for doing so is that, despite some differences in the ‘versions’ of liberalism, there are, nonetheless, prevailing and constant liberal principles and core assumptions. It is useful first to offer a few qualifications and clarifications. It is important not to lose sight of the fact that the term ‘liberal’ has been applied to the political beliefs of a wide variety of people. Liberals have views about the economic organisation of society, for instance; here we can detect a division in liberal thought between those on the political ‘right’ who believe that individual liberty must extend into the economic realm: that is, people must be free to buy and sell their labour and skills as well as goods and services in a free market which is subjected to minimal regulation. On the other hand, ‘left-leaning’ liberals recognise that the principles of political liberty and equality can actually be threatened by the concentration of economic power and wealth. This form of liberalism supports a much more interventionist role for the state in the regulation of the economy, in the interests of providing for basic human needs and extending opportunities to the less privileged. As we shall see below, these two strands of liberal thinking live on in neo-classical and Keynesian approaches to International Political Economy (IPE), which has developed as a discrete area of study within IR since the 1970s.

Liberalism, as an ‘ism’, is an approach to all forms of human organisation, whether of a political or economic nature, and it contains within it a social theory, philosophy and ideology. The result is that liberalism has something to say about all aspects of human life. In terms of liberal philosophy, liberalism is based upon a belief in the inherently good nature of all humans, the ultimate value of individual liberty and the possibility of human progress. Liberalism speaks the language of rationality, moral autonomy, human rights, democracy, opportunity and choice and is founded upon a commitment to principles of liberty and equality, justified in the name of individuality and rationality.

Figure 1.1 The relative growth in the number of international NGOs in the twentieth century.

Original source: B.B. Hughes (1993), International Futures, Boulder, CO: Westview Press, p. 45.

Taken from: B. Russett and H. Starr (1996), World Politics: The Menu for Choice, 2nd edn, New York: W.H. Freeman, p. 66

Liberal pluralists see a complex web of interactions in International Relations that goes beyond the mere interaction of states.

Politically this translates into support for limited government and political pluralism. We will summarise the main assumptions of liberalism below. First, we need to consider further the historical and intellectual origins of liberal thought.

LITERATURE BOX

The Brandt Report

The report North-South: A Programme for Survival, published by The Brandt Commission in 1980, is an example of liberal internationalist sentiment and Keynesian economic philosophy in practice. The ‘Brandt Report’ outlined the many and varied ways in which economic interdependence had made all of the world's peoples vulnerable to economic recession and world economic crisis. Coming in the wake of the breakdown of the Bretton Woods economic system and, in some ways, anticipating the debt crisis and recession of the 1980s, it called for worldwide cooperation and active political intervention to protect the worst-hit countries and to revive the world economy.

The suggestions of the Brandt Report are as relevant today, if not more so, than when they were originally suggested. The realisation that we now live in a world characterised by a single economic system has informed mainstream national economic policy around the world. The proliferation of bilateral and multilateral agreements aimed at liberalising trade and coordinating economic activity has picked up pace in the twenty-first century. The key influence in encouraging Free Trade Agreements (FTAs), integrated markets, single currencies and so on has been the assumption that economic growth and prosperity result from facilitating the operation of the single economic system and not resistance to it.

The global financial crisis and subsequent recession, which are ongoing at the time of writing, offer another example of the complexities of what the Brandt Report discussed. The crisis and recession spread from one state to practically all states in approximately one year, demonstrating the economic interdependence that now exists in international relations. The responses to it have also taken on increasingly international or even global characteristics. The crisis has in effect legitimised the report and the responses to it have been influenced its suggestions.

Origins

In this section we will outline the main influences on liberal IR, which we have identified as Immanuel Kant, Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill and John Maynard Keynes. For the sake of simplicity and clarity we have divided the origins of liberal thought into ‘political’ and ‘economic’ strands. We will then use these two broad divisions to contextualise the subsequent discussions of key themes within what we broadly term the ‘liberal perspective’ in International Relations. We hope that making this distinction between political and economic liberalism will help you find your way through a dense literature. However, you should be aware that inevitably there is some overlap between the economic and political strands of liberal thought.

In this section we begin with liberal idealism. In everyday usage the term ‘idealist’ is sometimes used in a negative, or pejorative sense, to describe a person who is considered unrealistic — a dreamer. However, it has a specific meaning in philosophy where it denotes certain beliefs about the nature of the world and the capacity of human beings for rational thought. Starting from the premise that the international system was something akin to an international ‘state of nature’ or ‘war of all against all’ (see chapter 2), Kant argued that perpetual peace cannot be realised in an unjust world. The only way that this state of affairs could be overcome would be for states to found a ‘state of peace’. Kant did not envisage the founding of a world government, or even the pooling of sovereignty, but, rather, a looser federation of free states governed by the rule of law.

Kant did not see this state of affairs coming about fortuitously, or quickly. While the application of Kantian thought to international relations has been dismissed as ‘utopian’, it is important to note that Kant recognised that, in order to achieve a just world order, certain conditions were necessary, including the establishment of republics, as opposed to monarchies or dictatorships (and, perhaps, a near-universal commitment to liberal democracy). Indeed, Kant held that only civilised countries, those countries which were already governed by a system of law and in which people were free citizens rather than subjects, would feel impelled to leave the state of lawlessness that characterised the international state of nature. There has been some debate about how Kant saw the relationship between republics and other forms of polity. However, Kant is frequently interpreted as suggesting that countries where people were not free citizens, but rather subjected to the rule of a monarch, perhaps, or a dictator, were much more likely to be belligerent and warlike. If this was the case, logically it followed that a world federation would only be achieved when all states were republics. Just as Kant believed that a state of ‘perpetual peace’ would not be realised in the near future, contemporary liberals are under no illusions about the barriers to achieving justice and the rule of law under conditions of anarchy, but, like Kant, many insist that this is an ideal to be striven for.

Republic: Traditionally this is a term used to describe a secular state in which there is a separation of power...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Liberalism

- 2 Realism

- 3 Structuralism

- 4 Critical Theory

- 5 Postmodernism

- 6 Feminist perspectives

- 7 Social constructivism

- 8 Green perspectives

- Conclusions, key debates and new directions

- Glossary of key or problem terms

- Further reading

- Index