![]()

1

Inceptual Questions

The study of newborn existence raises questions as to whether fundamental philosophical notions actually apply to the experiential world of the newborn. Are terms such as ‘lived experience,’ ‘consciousness,’ ‘subjectivity,’ and ‘intersubjectivity’ appropriate for describing a newborn’s existence? How can phenomenological inquiry proceed without being confident of the language we use? What considerations need to be given to the method of phenomenology for empathically approaching or accessing the world of the newborn?

A newborn is likely to experience the world in a vastly different mode than an older child or adult owing to differences in body-brain maturity and the pure temporality of natality. And yet, as adults we do have understandings, or at the very least, we carry out our day-to-day activities interacting with newborns with an assumed sense as to why they fuss, cry, sooth, settle, or otherwise act within and respond to the world. A phenomenology of the newborn explores such understandings not by an ethereal exploration above and beyond the way a newborn’s body and brain function, but instead by attentiveness to the knowledge that empirical sciences have generated—importantly, phenomenology is also alert to the philosophical presumptions underlying such knowledge.

Contemporary empirical infancy research shows that newborns come to possess complex, cognitive competencies that exceed their overt everyday actions (Rochat, 2001). Such research has the potential to inform our understanding of the newborn’s world as inhabited. Still, empirical researchers may all too readily lose sight of the lived meaning of newborn experiences by instead focusing on newborn behavioral development from an objectifying perspective—a perspective that sees newborns primarily as immature in their development. In other words, rather than wonder what a newborn’s subjective and inner life may be like, it focuses instead on the developmental accomplishments achieved by an infant from an external perspective.

What Constitutes the Lived Existence of a Newborn?

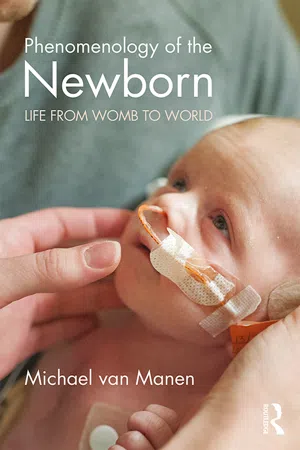

A premature baby has been placed in an isolette (a neonatal incubator). A sheet cast over the housing mutes ambient light just as the plastic structure itself attenuates sound. Only traces of the outside world seem to be allowed in. Within the isolette, rolled towels support the baby’s body in a position of flexion. The arms, torso, and legs shift in subtle shutters before settling in stillness. Eyes gaze, yet seem to lack a point of fixation.

What is life within the isolette like for this child? While it might be assumed that this premature infant is unaware of its external and internal ambience, this assumption is unwarranted. Do the gazing eyes not see? Does the fidgeting body not feel? What sensibility may actually be present in this baby? And, what words are appropriate to describe his or her existence?

For phenomenology, the term ‘lived experience’ signifies the living throughness of each moment of our existence. The “phenomenological thesis” says that experience is first and foremost pre-reflective, pre-predicative, and pre-linguistic (Romano, 2015, p. xi). For the most part, we do not think about our experiences as we live through them. This does not mean that our experiences are not meaningful, but rather that we do not reflectively dwell on these meanings while we are experiencing them. Our ordinary everyday lived experiences are largely taken-for-granted as we are absorbed in the ongoing happenings of our lives.

At times an event may prompt a pause, notice, or reflection. And in such contemplative moments, we may become aware of how meaningful a moment in our lives was. The point is that such meaning, which is at the heart of experience, is always already there, founded in the way we directly experience being-in-the-world as lived experience. For example, when a loved one shares in conversation the occurrences of their day, we nod both to confirm we understand the matter-of-fact happenings surrounding an event and also the meaningfulness of an event. We understand terms such as annoying, frustrating, invigorating, satisfying, and so forth because we appreciate the meanings that inhere in the experiences even before such terms are used to describe emotive reactions or feelings. While we cannot hazard if the fetus or newborn has contemplative capacities, we should wonder what meanings constitute their lived existence. We wonder how a newborn directly experiences the world.

The assumption and belief that the newborn experiences the world without meaning has already been largely disproved. We can simply no longer accept that the newborn “feels it all as one great blooming, buzzing confusion” as described over a century ago by William James (1890, p. 488). Research has shown that the newborn may already orient to differing smells (Marlier & Schaal, 2005; Marlier et al., 2007), sounds (DeCasper & Fifer, 1980), and touches (Butterworth & Hopkins, 1988; Rochat & Hespos, 1997; Rochat et al., 1988) in their distinctiveness. And yet the discovery that a newborn discriminates between smells, sounds, and touches does not answer what meanings reside in such discriminating sensuality.

The challenge to access the experiential world of the newborn, or even an older child or adult, is that we need to somehow turn towards experience as meaning arises (as it is lived through). Yet, as soon as we try to introspect an experiential moment, it becomes objectified by our reflective glance. If we try to attend to an experience as we live through it, the lived through experience itself cannot help but be changed to an experience of reflecting. We can only retrospect the meaning of experiences. So, if we aim to capture an experience after we have lived through it, we are always already too late. Similarly, by analogy, we tend to objectify a newborn’s experiential world by using words such as agitation or distress. A phenomenological, reflective glance aims to understand a living moment of existence.

[R]eflection is not at all the noting of a fact. It is, rather, an attempt to understand. It is not the passive attitude of a subject who watches himself live but rather the active effort of a subject who grasps the meaning of his experience.

(Merleau-Ponty, 1964a, p. 64)

Reflecting phenomenologically on experience is not an act of abstraction, conceptualization, or theory generation; nor an endeavor of self-analysis, meditation, or soul-searching. Rather, it is an effortful questioning of experience, engaging with our own existent sensibilities, gaining an experiential grasp of being-in-the-world.

In so far as we can appreciate or recognize an experience as resonant with our sensibilities, phenomenological inquiry aims to bring these sensibilities to concrete, experiential understanding. But this understanding encompasses more than expressible propositions, statements, or facts. There are primal meanings to experiences that may be ambiguous, indistinct, or simply resistant to articulate in their primality (Ricoeur, 1966, p. 208). As adults we can reflect on an experience of a moment of pain or anguish, delight or joy, or any other stretch of experience. Yet, we may have a hard time articulating or finding words that adequately describe such lived experience even if the experience is our own. There is always something about an experience that may evade reflection: there always remains a difference between the lived and the articulated (Merleau-Ponty, 1962, p. 393). The lived meanings of lived experience are subtle and elusive, ambiguous and complex. This pre-reflectivity of lived experience is a challenge to our efforts to bring experience to language.

Phenomenology is not as naïve as some people pretend. It does not presuppose that what appears is completely outside of language, but it does presuppose that what happens and appears to us is more than what can be said about it and what can be argued for or against it. The crucial point is not to assume that there is something given outside of language, but to concede that language precedes itself.

(Waldenfels, 2007, p. 88)

The language of phenomenological reflection attends to the manner in which an experience is given to consciousness, to gently lift that which otherwise may be readily passed over by awareness to (re)call the experience to presence. We must ultimately name or bring to language meanings as they are experienced, recognizing that some meanings are tacit in their implicitness as they are embedded yet unspoken in text. In studying the subjectivities of the newborn we need to constantly question the language we use in our interpretations because language itself shapes our primal perception of experience. As Gadamer (2004) writes, “All understanding is interpretation, and all interpretation takes place in the medium of a language that allows the object to come into words and yet is at the same time the interpreter’s own language” (p. 390).

A discussion of lived experience should alert us to the primality of existence we experience in the presence of the baby’s wandering gaze, as we watch the baby shudder before stilling. The image evoked in the description of the newborn lets us understand something, even though we may not know what this is or struggle to use words to describe it. We experience that a lived experience exists in the presence of a newborn whose look confirms a being here. Yet, we may wonder how such being differs from that of the adult. We need to consider what language we use to convey a sense of the lived experience of a newborn.

What Kind of Consciousness is Composed in a Newborn’s Existence?

In an adjacent isolette, a newborn receives analgesic, sedative, and paralytic medications as we struggle to maintain oxygenation. The baby lies splayed. Only the chest moves, vibrating in response to the airflow of the oscillation machine. With muscles relaxed, she cannot move, let alone open her eyes. As we are talking next to the isolette, the baby’s heart rate rises.

When watching this baby we cannot help but wonder, does this baby experience anything? Does she feel pain or discomfort, isolation or loneliness? Is she somehow aware of our presence? If our spoken words have an effect on the physiology of her heart rate, does that mean that they also affect her mind? And if so, would that be a sign of conscious awareness?

Consciousness refers to the awareness of our existence of being-in-the-world. It describes a state or condition of sentience—a capacity to feel, perceive, experience. The term ‘consciousness’ also implies self-awareness—a capacity to distinguish self from world. But we need to make a further distinction between a condition of sentient self-awareness and reflective self-awareness. We speak of someone being conscious as being responsively aware of objects and people around him or her; and, we also speak of being conscious as being self-aware whereby a subject is aware of his or her own subjectivity.

From a phenomenological perspective, consciousness is allied to the notion of lived experience as the “intrinsic feature” of the way we find ourselves experiencing the world as a subject (Zahavi, 2005, p. 20). Consciousness occurs by way of our direct perception of the world. Husserl (1991) describes this primordial awareness as a primal impressional consciousness—a kind of proto-consciousness structured like a temporal streaming ‘now-awareness,’ that includes a sense of the retentional ‘just-now’ and the protentional ‘next-now’ (p. 50). Such a structure of consciousness would seem to be needed to hear music as a melody compared to a series of tones without coherence: a capacity of which a newborn appears capable, emerging in likely a rudimentary form as early as 28 weeks gestation (Draganova et al., 2007; Holst et al., 2005). Primal does not mean unconscious but preconscious. Preconsciousness is already a form of consciousness. At this level we should assume that a newborn is indeed infused with primal or preconscious consciousness such that a preconscious awareness is not (or not yet) reflectively aware of itself.

A phenomenological understanding of consciousness does not eclipse the meaning of the unconscious. It is not that we carry out our activities unconsciously but rather that we tend to be immersed, absorbed, engaged, and preoccupied by objects, events, and other happenings in our subjective day-to-day existence. Even if lived experience is not explicitly conscious, we do live in a context of anticipation. We slide from one encounter into another, and one experience sinks into the other, and indeed in such a way that we do not bother about it. We are immersed in the temporally particular situation and in the unbroken succession of situations that we live through. We are engrossed in it; we do not view ourselves or bring ourselves to a meditative, deliberative, or reflective consciousness as now this comes along or now that (Heidegger, 1962, p. 92).

Subjectivity as related to conscious self-awareness has long been a concern of phenomenology, as witnessed in the classic writings of Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, and Merleau-Ponty and in the recent writings of Marion, Nancy, Malabou, and Zahavi. It is not enough to say that phenomenology regards things from a first-person point-of-view because this is true of many other qualitative research methodologies such as narrative inquiry, social constructivism, and perception studies. Rather, for phenomenology subjectivity is bound up with lived experience “because the subject that I am, when taken concretely, is inseparable from this body and this world” (Merleau-Ponty, 1962, p. 475).

Lived experience is subjective in that each conscious experience we have appears as our own—as my experience. It is not that phenomenology posits that conceptually a self exists but that our conscious experience of the world is implicitly marked by “first-personal givenness” to myself as a subject (Zahavi, 2005, p. 22). It is the sensibility that, when I have an experience (something happens to me, or I perceive something) that I am primordially aware that this is my experience and not someone else’s. However, this awareness is only primordially mine—I know that I am this experience. For example, this pain is me. Pain is not some-thing that I possess like an object. Rather this pain is my subjectivity. We may see evidence for such a sensibility in the infant who responds to self-touch differently than the other-touch of an object or other subject (Butterworth & Hopkins, 1988; Rochat & Hespos, 1997; Rochat et al., 1988) such that we may speculate that even from early gestation there is a primal dimension to our awareness of self as same, rather than other, even if such distinctions are incomplete or emergent.

For the newborn, the world presents itself as a bodily being-in-the-world. Rochat (2001) describes this as our “embodied self” whereby the newborn world consists of direct and immediate perception, contrasting it with “intentional self”: the self-conscious reflective awareness of one’s “own body as a differentiated entity in the environment” (p. 76). Rochat postulates the self as embodied to develop from as early as within the womb while the self as intentional subject only begins to emerge around the second month of life. In other words, it is only with time that infants are able to “bypass the immediacy of perception to start reflecting on it” (p. 180). I do note to the reader that Rochat’s use of the word intentional differs from the notion of intentionality as used in the phenomenological literature.

From the work of Rochat and others it may be tempting to believe that different kinds of consciousness exist, or that it is only when consciousness meets a particular level of development that meaning is possible. Yet, if meaning is ultimately founded in the manner in which we live through the world in the immediacy of perception, it is hard not to assume that the consciousness of the newborn is meaningful.

The notion of newborn subjectivity is only problematic if we consider the self as a phenomenally distinct, unitary, or pure entity existing over and above our stream of conscious experience. If not, how could we know whether a contemplative self truly exists. Instead, we need to consider subjectivity as exis...