- 162 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

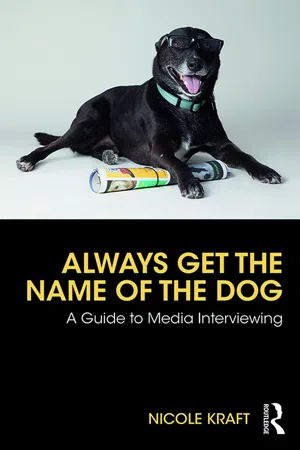

About this book

Always Get the Name of the Dog is a guide to journalistic interviewing, written by a journalist, for journalists. It features advice from some of the best writers and reporters in the business, and takes a comprehensive view of media interviewing across multiple platforms, while emphasizing active learning to give readers actionable steps to become great media interviewers. Through real scenarios and examples, this text takes future journalists through the steps of the interview, from research to source identification to question development and beyond. Whether you are a journalism student or an experienced reporter looking to sharpen your skills, this text can help make sure you get all you need from every interview you conduct.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Always Get the Name of the Dog by Nicole Kraft in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Communication Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Success Starts with Research

I often read this quote from the Bhagavad Gita to my journalism students about cultivating a beginner’s mind. It’s about a student going to a teacher saying, “I want you to teach me everything you know. I want to sit at your feet and learn from you. So here I am. Teach me.” The teacher just starts pouring a cup of tea. And keeps pouring and pouring. The tea is overflowing out of the cup, and the teacher keeps pouring. The student says, “Why are you pouring the tea so it’s overflowing onto the floor?” and the teacher says, “This cup of tea is like your mind. It’s overflowing with what you already think. There’s no room for me to teach you, because it’s already full of your own ideas.”(Sarah Saffian, author and writing coach, personal interview, 2014)

Figure 1.1 Learning to capture notes accurately and completely is one of the most challenging aspects of reporting.

Source: Creative Commons/Jacinta Quesada/FEMA

How much research is enough before you start interviewing? Enough so that you have all of the answers you need for an intelligent conversation.

“There’s some level of information that you do need to have and that you should have otherwise you look like you don’t know what you’re talking about,” says award-winning journalist and author Mac McClelland:

I’ve been talking to someone, and I realized sort of mid-interview, it wasn’t my job to become a Ph.D. on this subject before we had this conversation, but there was definitely a minimum level of information and understanding that I should have had about what we were talking about before I went into it.Because I didn’t have that, I didn’t use my time as well as I could have. I wasn’t asking as smart of questions as I would have come up with this if I knew what … I was talking about.(Mac McClelland, personal interview, 2014)

Before embarking on a journalistic interview, some basic questions should be asked and answered by you as the reporter:

- What exactly is the story about?

- How many angles are there?

- Which angle is the one to pursue now?

- Which type of sources would be best?

- What person or organization will be the best source, and how will you get in touch with them?

- What will you ask them?

The more you know, the more likely you are to determine what the reader needs to know. Research comes in all different forms—from relatively pedantic to cutting edge.

Figure 1.2 Searching the web for story ideas and sources has become common practice in journalistic reporting.

Source: Creative Commons

In the Beginning

The question asked by most new reporters is, “Where do I start?” As simplistic as it sounds, a straight Google search can be the best place to launch research on a story subject or a source. It can provide background information, previous articles, and other support documents and websites. Try filtering by date and looking at the news tab to vary your search and focus on what information you are actually seeking.

Let’s consider the story idea of a new bike polo club forming in your neighborhood. Before you even begin to report, it would be useful to look up what exactly is bike polo, how is it played and what are the rules? Go to the news tab on Google and see if anything has been written recently so you might identify some potential sources. Visit YouTube to check out videos of people playing bike polo so you can envision how the sport works. Search on Facebook for people in your area who play bike polo.

The goal of this research is not to become an expert in the subject but rather to put yourself in the mind of the reader. What is it exactly they would want to know, and how can you (a) find sources experienced in this subject to (b) share their knowledge in a way that you can convey the subject meaningfully to the reader?

But to converse with an expert on a topic—from cancer research to a participant in an obscure sport—it is imperative reporters have a base level of understanding, so they can converse meaningfully. The fastest way to turn off an interview subject is by approaching them from a position of weakness—you have no idea what they do or what you need them to provide for the story.

Good reporters live by the adage, “I don’t know what I don’t know.” That means approaching every story and every interview like you know virtually nothing about it. But the last thing you want to do is go into your interview in that state. Building knowledge from the ground up by reading prior articles and documents, asking questions of sources you may not even use, and flushing out as much background as you can will help shape a meaningful conversation/interview with sources.

Despite what your mom or elementary school teacher told you, there are, indeed, stupid questions—specifically ones with which you should have come armed with information, like:

- What is your name and your job?

- What is background relevant to this subject?

- Why are you relevant for my article?

Imagine you are writing a piece on a new company and your first question to the CEO is, “What exactly is it this company does?” How do you think he or she will perceive you from that moment forward?

Your research should provide you with this basic information on an interview subject, as it is often readily available in the public sphere or can be obtained from other sources before you start. You may still want to confirm the information to make sure the source you have is correct.

“I see you grew up in Philadelphia,” means you did your research, but they might actually say, “I’m actually from a suburb called Abington.” You get credit for knowing the key info, but you have fine-tuned your facts even further.

Figure 1.3 Scott Simon said research is important before forming questions, so a reporter knows what he or she wants to talk about under the interview circumstances.

Source: Creative Commons/Tracie Hall

NPR’s Scott Simon talked research with “Y-Press,” a student-run journalism program out of Indianapolis, as part of its “Power-Of-The-Question Project.” He said research is important before forming questions, so a reporter knows what he or she wants to talk about under the interview circumstances. He urged interviewers to have a level of expertise, but not to get locked into a strict script:

I would have to ask myself, “Why are we talking to this person, what do we want to know from them or about from them.” At the same time, you have to be responsive to what they say. There is nothing wrong with having a few questions in your mind, but you can’t become so devoted to them that you don’t notice what someone is saying. Somebody is saying something so you have to listen, and you have to have enough knowledge to follow up on something they say.(Y-Press, 2009)

The art, according to author and writing coach Sarah Saffian, is to find the balance between being prepared and being flexible. She also cautioned against having so much information that you pre-judge your subject enough to skew your interview:

As much as I advocate doing the homework, and knowing about the person, and knowing about the context where the person resides, you are really trying to avoid prejudgment as much as possible. That can really dictate the interview so much that you come home and you don’t have any fresh information. You didn’t actually gather information, which is supposed to be the point of any reporting.If you go in there with all the answers what are you going to learn?(Sarah Saffian, personal interview, 2014)

Box 1.1 How Much Reporting Is Enough?

Charlie Leerhsen, a former editor at Sports Illustrated and People, and author of Ty Cobb: A Terrible Beauty, says he answers the question “How much reporting is enough?” with a simple response: “Too much is enough.” Leerhsen says the reason to do thorough research is not just for the data and the facts that it yields, but most importantly to make you confident that you can talk about your subject.

“Ian McEwan, the great novelist, said as a nonfiction writer you want to do enough reporting so you can really walk around inside a subject,” Leerhsen says. “You want to do enough reporting so you can really feel confident to put out the story that that you’ve learned through your reporting. Without enough, you’re handing out scraps and bits, and you don’t feel confident yourself.”

Source: Charlie Leerhsen, personal interview, 2014

The Angle

There are often multiple ways to tell a story, and each one is an “angle.” It is the direction an article will take, the perspective it will provide the reader, and how the author will shape what the information is provided in the story, via the facts and sources utilized.

To determine the angle, the journalist needs to consider what they want or need the reader to know. It’s the lens through which a writer filters information he or she has gathered, and there may be several different angles to pursue from a single news event or feature article.

Consider a news article about a new hospital expansion being built, which results in the closing of a highway off ramp that serves a community. A story could be written about the hospital expansion itself and what it will offer the community. An article could also be written about the impact on the neighborhood of the ramp closing. Two angles to the same story, and each one requires very different sources answering very different questions.

Valentine’s Day needs to be covered by most news publications in some way every year, with a unique angle. That angle might be how to spend Valentine’s Day as a single person, or finding a couple married 70 years who still celebrate Valentine’s Day. It could be visiting a chocolate factory to see how holiday confections are made or spending a day at a winery that makes custom blends and labels for those in love.

Each one is a different angle. Each one would be researched differently. Each one requires different sources.

The research into a story might also allow for the localization of national stories. Consider covering the September 11 anniversary by profiling someone from your community who survived the terror attacks. You could also find in your community transplants from Philadelphia who sha...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Boxes

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Welcome to the Conversation

- 1. Success Starts with Research

- 2. Something about Sources

- 3. Getting it Down

- 4. Location Matters

- 5. Questions and Answers

- 6. Tricks of the Talking Trade

- 7. Covering Sports

- 8. Speeches, Press Conference and Meetings, Oh My

- 9. Interviewing across Media

- 10. Ethics of Interviewing

- 11. There Are Stupid Questions—But You Don’t Have to Ask Them

- 12. Let’s Talk

- Resources

- Index