![]()

CHAPTER 1

Fundamentals of Schooling

Like many high-school educators, I began my career teaching and coaching. My father was also an old-school football coach who stressed fundamentals and passion for the game. He approached each game with a sense of urgency as if his life was on the line, and his coaching philosophy centered on very specific techniques such as stance, shoulder skills, form tackling, and physical conditioning. These tenets had to be met before adding plays to his team’s repertoire; he was successful because his teams were firmly rooted in the basics of the game. He was also tenacious about working hard, winning and doing things the right way.

A school with a high poverty rate must have a strong foundation because it must overcome a variety of tremendous obstacles. The symptoms of these obstacles are demonstrated in high rates of absences and behavioral incidents. In the world of sports, some teams enjoy success and win championships because they simply have more talent than other teams. While students in poverty certainly have equal educational capacity as those students not in poverty, their economic disadvantages create a chasm that can only begin to be closed if a school has a foundation for success. In athletics, the team that is less talented or more disadvantaged beats opponents of superior talent only when it has strong fundamental skills and team unity and performs with inspiration instilled by great leadership. The schooling process for students in poverty requires a similar combination: obstacles including disadvantaged backgrounds can be overcome by strong fundamentals and inspiration. The fundamental elements of the schooling process that give students in poverty the best chance to succeed are relationships, leadership, safety, outstanding teachers, accountability, intangibles (inspiration, competition, urgency, and passion), teamwork, and opportunity.

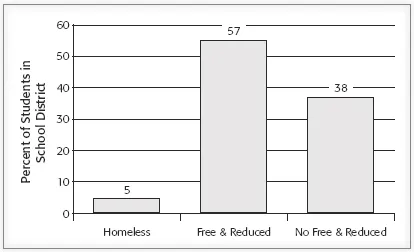

Figure 1.1

Bristol, Virginia, Public Schools Demographics: The New Middle Class

It is abundantly clear that schools can no longer educate with a central focus on middle-class children with two parents, a constant source of quality food, and adequate supervision. Educating every child in a school is certainly critical; however, the new middle group, and the majority of students in public schools, are not middle-class children but rather students in poverty. The foundations of successful schools are vital because students in poverty face greater barriers and more obstacles. Figure 1.1 depicts the economic levels of public-school students in Bristol, Virginia. Bristol is similar to many communities in the country in that the majority of students in our district are students in poverty.

Relationships

By now every American educator can recite Dr. James Comer’s (2001) famous quote that “no significant learning occurs without a significant relationship.” The ability to foster relationships not only with children but with families and the community at large is essential for educators. Families in poverty often have a history of distrust of public institutions, including public schools, due to their own life experiences. In addition, the history of American public schools has often perpetuated distrust and inequities. To some American citizens, desegregation is a far-off relic of yesteryear and an example of how this nation has overcome obstacles. For others, segregation will always serve as a painful reminder of gross injustices related to public schools and society in general. Even today, as a result of the No Child Left Behind Act, educators formally categorize children in subgroups related to race, disability, and socioeconomic status. The intent of the law is a noble effort to address categories of students and improve their learning; however, when students in poverty are displayed as achieving at a lesser rate, it is a painful reminder of the privileges some children have that a growing number do not. The history of public schools coupled with the challenges families in poverty face makes relationships fundamental to schooling.

Schools that strive to forge positive relationships with the families they serve give their students the best opportunity for success. This is especially true for families in poverty who often mistrust schools as oppressive government agencies and educators as members of an aloof higher caste. This book weaves the importance of relationships throughout each chapter and provides a multitude of specific methods to engage families, children, and the community. While the specific methods are often related to programs or school initiatives, it must be noted that relationships, not programs, shape students (Milliken, 2007).

The central tenets of developing relationships with students in poverty are trust and dignity. Establishing trust is essential because it is a condition of community, and developing a community that supports the educational process is particularly challenging in high-poverty areas (Strike, 2007). When schools forge a trusting relationship with students and their families, it instills confidence in the schooling process and it brings the family to the table as a partner in the child’s education. Trust is established through transparency and honesty. It is also nurtured through mutual respect and consideration of families in poverty who have little beyond their own dignity. All employees in the school system, from the bus drivers who greet students first in the morning to teacher aides, paraprofessionals, cafeteria workers, secretaries, custodians, and teachers, should treat families with trust, dignity, and transparency. For school leaders, creating professional development opportunities that hone all employees’ skills of working with the public is critical. Prior to any professional development, school administrators must interview and deliberately select candidates with traits that are inviting and engaging to all students and their families. Hiring personnel who possess strong communication skills and an ability to forge positive relationships simply by treating people with dignity and respect will increase a district’s capacity for family involvement in student learning. This proactive step can reduce community problems and improve a school’s image and student achievement with far less need for reactive training following a public relations problem or incident.

It has perplexed us over the years to see school officials take time to show off an entire building and brag about the school’s programs to the college professor or business owner whose children are entering the school, whereas parents in poverty are quizzed in great detail about their living arrangements and residency and provided little help in completing the litany of school-related documents. Dignity means treating all families with equal regard. Dignity transcends words and is wrapped equally in body language and actions. Dignity also means that it is out of bounds and unethical for educators to make fun of people in poverty. The courageous educator or school leader cannot be afraid to confront a colleague who jokes about a student’s mother who is overweight, has poor dental care, or has body odor. The age-old conversations behind the closed doors of the teachers’ lounge or even the principal’s office, in which educators make fun of families in poverty, are never acceptable. Teachers and other personnel who engage in such behavior are also indicating that they do not have the desired relationship skills or the compassion and understanding that the school, its students, and the community deserve.

It is clear that the relationship between educator and student has the potential to be profound. In fact, it could be argued that the only relationship that is more pertinent and life-shaping than the one between educator and student is that of parent and child. Because many students in poverty come from nontraditional families that lack stability, the relationships established in the schoolhouse are central to their lives.

I am frequently reminded of Sophie, who came from abject poverty and familial dysfunction. She was as rough as anyone in our school at the time, and she would fight over any perceived slight or insult. We suspended her for drug use, fighting, disruptive behavior, and disrespect to her teachers; she had all the makings of a high-school dropout. Our dynamic chorale director, Lois Castonguay, however, found a glimmer of hope in Sophie and worked to develop her smoky voice into a stunning virtuoso performance in the choir. The relationship between Sophie and Mrs. Castonguay was not smooth or warm every day, and Sophie was never a model student, but she loved choir and benefited greatly from the support, high expectations, and positive, structured outlet it provided. Undoubtedly, it was singing at school every day that got Sophie there, and it was the annual spring concert in which she was a featured soloist that got her across the stage to take her high-school diploma.

One of the ways that I have celebrated relationships over the years has been through a program called the Golden V. The V represents our high school, Virginia High, and the Golden V ceremony celebrates the success of our school’s most outstanding students. This program, which culminates a successful student’s educational career, also allows students to recognize the educator of their choice. The students are awarded a trophy, and their various academic accolades are recited during a dinner event; the student then reads an essay about an educator from our school system and the profound impact that person had on the student’s life. Over the years, I have heard students’ essays about teachers, principals, and custodians, and what stands out in the students’ poignant prose is that these profound relationships were established because the adults cared deeply about their instruction, student learning, the children they touched every day, and their lives outside the realm of school. The students’ inspiring testimonials speak volumes about what is important to them. They often state that a teacher “got me through school.” One of the most meaningful speeches I have heard was given by a student who was heading to college with aspirations of becoming a famous television news anchor. She went on to say that if this goal didn’t work out she would be okay because she would follow the example of Mrs. Fuller and “come to work every day with smile, be kind to everyone, work hard, be a great mother, have great spirit, and care deeply.”

Relationships are a vital component of the foundation of success of students and schools. While educators often talk about the importance of relationships, school officials must be strategic in their approach to developing relationships that are part of every aspect of educating students in poverty.

Leadership

Students in poverty are easily lost in the shuffle because so few have anyone at home to advocate for them. This is why school leaders must be willing to take on the challenges of poverty and address the problems such students face at every step along the way during their school-age years. School leaders must be willing to bridge social and cultural gaps to develop relationships, keep these children in school, drive down their dropout numbers, and increase the graduation rate for a population that faces more obstacles than supports. The proactive public-school leader must be able to connect with students in poverty and demonstrate to other stakeholders that academic success for this growing group of students equates to better community success for years to come.

While increasing graduation rates is vital to improving the lives of individual students in poverty, school leaders must connect with community leaders and effectively articulate that education is the key to reducing generational poverty and the strains this syndrome has on localities. A public-school system should also be able to mark success by driving the poverty level of a community down, an effort that requires intensive communication and cooperation among local social, civic, business, and political leaders.

The mission of every community must be to reduce the number of its citizens in poverty, and school leaders must reach out to other agencies to articulate this goal and establish specific steps and strategies to achieve it. Certainly this is a daunting charge, but no other entity has better or more effective access to students and families in poverty than schools; and this is why it is so important for school leaders to build trust with impoverished families. Of course, this aim is difficult to achieve when principals are viewed as heavy-handed and teachers as aloof and out of touch with the challenges impoverished families face. But if school leaders are skilled and willing, they can advocate for their students in need and affect changes in perception, treatment, acceptance, services, and the very approach and attitude to assisting the impoverished families in their community.

It is our perception that educators sit and wait too long for someone else or some other agency to take the lead on community and even state and local issues that impact schools. Instead of waiting for other agencies to intervene on behalf of the students, school leaders have to take the wheel and drive the ship, especially on student matters. From our perspective, there is no greater or more pressing student matter than the staggering growth of poverty in our community. Therefore, it is up to educational leaders to express the issue, present strategies for reversing the trend, and advocate for poor students and their families to other agencies and entities that can help schools help them.

School leaders are community leaders and even icons in some cases. Principals, coaches, and teachers who have devoted their careers and lives to children and families in their community have the power to dramatically improve their town, city, or county. Such leaders can achieve this goal more effectively if other community leaders will join them in a shared vision of a better way of life for the people they serve. Council members, social workers, business owners, civic leaders, and police officers are equally recognizable and influential in a community, and by working closely with them, school leaders can affect positive and sustained change that benefits everyone and every agency in the locality.

There is a direct correlation between strong, stable shared leadership and student success. In fact, a recent study conducted by researchers Kyla Wahlstrom and Karen Seashore (2010) from the University of Minnesota College of Education found a direct negative effect of principal turnover on student achievement. In addition, the study found that student achievement is higher in schools where principals share leadership with teachers and the community. Leadership characteristics come in many varieties, all of which can lead to success. Regardless of the leadership style, leaders in high-poverty school districts must advocate for the needs of students and articulate to skeptical citizens how public schools help students in poverty and the community as a whole. Leadership must be supportive of addressing poverty at every level, including school boards, executive administrators, principals, and teachers.

While the vast majority of educators are dedicated to their craft and the children they teach, many are unaware of the dire conditions those children return to every afternoon when they leave school. And while teachers may fully understand the impact they have on their students, many do not possess the skill sets and perspective required to forge positive relationships with families in poverty and make a true and effective difference in the lives and prospects of economically disadvantaged children. Therefore, transforming the mind-set of all school personnel is critical. Visibility in the buildings and in the community is essential for a transformational leader. Specifically, principals need to visit each classroom every day.

Over the years, we have heard a multitude of excuses why principals cannot visit each classroom daily. But the truth of the matter is that effective school leaders are always watching instruction and student learning. The primary purpose of public schools is student learning, and the chief priority each day for principals must be to visit classrooms because their consistent presence and visibility alone can reduce discipline incidents, improve instruction, and enhance school climate dramatically. Even as district leaders we try to visit schools and classrooms every day. This is a practice we mastered as assistant principals, because visiting schools, teachers, principals, and students empowers us as instructional leaders as much as any other aspect of our positions. Transformational leaders who truly envision and enact change visit classrooms, the frontlines of learning, to observe instruction and increase their awareness of student and teacher needs. The effective school leader is also visible in the community. Upon hiring our new personnel, we remind them they always represent the school district whether they are shopping at Wal-Mart, eating at a local restaurant, worshipping, volunteering, or attending community events. Such measures put you in touch with your school community, make you more accessible to the families you serve, and endear you as a vested member of the community as a whole.

Being visible moves beyond walking the halls and visiting each classroom every day; it also means being constantly accessible to a high-needs community. Accessibility means finding ways to break down the barriers those families in poverty face. Moreover, effective school leaders keep abreast of community needs. If the community would benefit if the schools expanded before- and after-school or summer offerings, then dynamic school leaders work to reach that goal. Barriers for families in poverty arise from the second the student crosses the schoolhouse threshold. The school leader who understands these needs does not turn the family away for lack of paperwork, but instead assists in the registration process and sets timelines for completion of documents while making sure the student does not miss valuable instructional time.

Many texts and articles on leadership have been written, and most have some information that is helpful. Robert Marzano’s (2005) School Leadership That Works and Stephen Covey’s (2004) 7 Habits of Highly Effective People are for many principals the gospels of administrative philosophy. Beyond trust, visibility, and transparency, effective leaders in high-poverty areas must have a burning desire to tackle the multitude of issues associated with their demographics. Further, leadership must hold a conviction that the purpose of public schools is to serve their students, families, and community. Service means meeting students and families where they are in order to deal with the multitude of...