![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Darwin’s Christmas dinner

At Port Desire

There is a story which sums up the development of prehistoric archaeology.

In 1833, the Admiralty survey ship, The Beagle, was moored off Port Desire on the coast of Patagonia. It was here that its most famous passenger, Charles Darwin, sat down to his Christmas dinner. If the occasion was traditional, the menu certainly was not, for much of the food eaten on the voyage had to be of local origin. In this case it included a kind of ostrich which he himself had shot. At the end of the meal, the bird had been reduced to its head, its legs and a wing. It was at this point that Darwin realised that he had just eaten a new species. The leftovers were collected together and documented for their return to England, where the remains of his dinner were enshrined in the scientific definition of Rhea Darwinii (Desmond and Moore 1991: 144–5 and 225).

Darwin’s experience was rather like that of the field archaeologist, for his work was based on material evidence. During the early nineteenth century natural history could be a destructive business. Before the adoption of photography, the best ways of describing animals were by trapping or shooting them (Barber 1980). They could be classified, illustrated and discussed, but in many cases this was only possible because these creatures had been killed. In time, photographs were to provide another medium for capturing their appearance and for recording their behaviour in the wild. Darwin’s fieldwork had its counterpart in archaeological excavation which also involved the elimination of the very phenomena that it set out to record, but it is hard to see how it could have been otherwise. We may find it troubling that Darwin should have combined hunting with natural history, but he would have achieved much less if he had used other methods of collecting information. In the same way, an archaeology based entirely on surface remains would have been quite incapable of coming to terms with the complexity of its source material.

The comparison between archaeology and Darwin’s field research has other aspects, too. Like the study of history, both involve the preservation of memories. A full description of the rhea would involve the appearance of the bird before it was cooked, just as the features revealed by excavation must be recorded before they are disturbed. The dead animals on which such pioneering studies depended have much in common with the extinct objects recovered by digging. The creatures were reanimated from lifeless corpses into vivid pictures and from field notes into documents, just as the remains on Darwin’s dinner plate had to be studied and described before they could take their place in the scientific literature. These published accounts preserved the memory of discoveries that were already receding into the past. It was those texts that provided the basis for more ambitious interpretations.

The same was true of nineteenth century archaeology, for it was during this period that it began to change from an essentially literary pursuit into a more empirical discipline. For centuries, interpretations of the remote past had been built around written accounts, from the Bible to the works of the earliest historians. In Europe this meant that the sequence did not extend much further back than the Classical period, with the result that a disproportionate number of ancient monuments were attributed to the Greeks or Romans and their enemies. That perspective changed quite slowly because of the difficulties of building a chronology for earlier periods (Trigger 1989: chapters 2 and 3). On the other hand, the growing contacts between excavators and researchers in the sciences, including Darwin himself, resulted in the observations made in fieldwork gaining a new legitimacy. That development is marked by a greater concern with record-keeping. There was a gradual realisation that description and documentation were as much a part of archaeology as the use of literary evidence, and that is why some of the major monographs published at that time can still be used as a source of information today. It is important to understand the authors’ original intentions, but, as secondary sources describing observations which could never be repeated, these studies ran in parallel with other records of scientific work; and, like them, they preserved the memory of information that might otherwise have been forgotten.

In their published form the texts produced by archaeologists became historical documents themselves, subject to the same kinds of scrutiny as other writings originating in the past. They also influenced conduct in the future, for they provided some of the materials through which later generations would come to terms with antiquities. These sources contribute to the presentation of what has become known as the ‘heritage’, but they do so at one remove, for, unlike historical documents, such accounts are not the raw material on which interpretations are based but simply a series of descriptions of past encounters with that evidence. Even with this limitation, they contribute to a form of memory that is intended to serve a wider audience. Indeed, collective memories of this kind play such a large role in contemporary politics that it is increasingly difficult for archaeological fieldwork to dispel the myths that become established.

One obvious example of such a myth is the existence of an ancient Celtic nation (Chapman, M. 1992). This has been important in Brittany where the great megalithic tombs of the Neolithic period were once interpreted as the work of the Veneti, who mounted such sustained resistance to Caesar. That myth, which was important in the growth of Breton nationalism, has been rejected by prehistorians, and yet it survives in popular belief in the exploits of Asterix. A similar kind of memory contributed to Darwin’s experience off Port Desire. Why did he eat the rhea as part of a formal meal? On one level, Darwin was following the tradition of the Christmas dinner. On another, he was celebrating the origin of Christianity, a system of belief whose very significance his later work would do much to undermine. Christmas was one of its main festivals, and the sequence of rituals in the ecclesiastical calendar traced the course of a narrative that had been repeated for nearly 2000 years.

Two millennia were of little account in Darwin’s research. His observations in South America did much to influence his view of natural selection. The rheas he had encountered in Patagonia played a small part in the theory of evolution, but the outcome of his investigation was fundamental, for it led him to conclude that human beings had originated at a much earlier date than had been implied in established sources, including the Bible. His thesis was unwelcome to the clergy, but even among his own followers it necessitated a new approach to the past. It enabled people to investigate human antiquity in a way that had been literally unthinkable when it seemed as if our species was created fully formed. It may be no accident that it was while Darwin was working towards these conclusions that the word ‘prehistory’ was invented (Chippindale 1988).

About prehistory

Prehistory is a term that can give rise to problems, although many of these stem from the ways in which the concept was applied in the nineteenth century. Taken literally, the word relates to the investigation of societies that do not have records or other written sources. They are prehistoric because they cannot be studied by the methods of historians. In Continental usage this has been complicated by the use of another term, protohistory, to refer to the time in which communities without written testimony of their own existed concurrently with societies that did have documents; generally speaking, that was in the first millennium BC (Hawkes 1950). For the purposes of this account, I shall adhere to the simpler scheme.

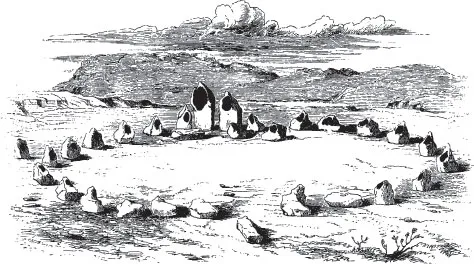

Unfortunately, the word prehistory has not been used consistently because of the way in which archaeology and ethnography overlapped in Victorian thought. In 1865, Sir John Lubbock published his famous book Pre-historic Times. Its full title is rarely quoted: ‘Pre-historic Times, as Illustrated by Ancient Remains and the Manners and Customs of Modern Savages’ [my emphasis]. In keeping with that scheme, the section on ‘The antiquity of man’ leads into three others concerned with living communities. Among the topics considered are: ‘Progress among savages’, ‘Skilfulness of savages’, ‘Ideas of decency’, ‘Curious customs’, ‘Low ideas of the deity’, ‘Moral and intellectual inferiority of savages’, ‘General wretchedness of savages’ and, rather oddly, ‘Neatness in sewing’. These follow a lengthy discussion of the archaeological sequence in selected areas of the Old and New Worlds, and the implication is clear. Even during the nineteenth century, there were communities whose ways of life were directly comparable with those of prehistoric peoples (Figure 1.1). These were the groups who had been left behind in the course of social evolution and for the most part they were also the ones who had to be educated in the ways of civilisation. Again that notion was influenced by the work of Darwin, although it was actually Herbert Spencer who extended the principles of natural selection to the study of human society (Trigger 1989: 93). By now the very idea of prehistory had taken on pejorative connotations.

Although that kind of conjectural history is no longer fashionable, it has had a longer currency than is sometimes supposed, for its approach is not all that different from the fashion for cross-cultural analysis that was such a feature of processual archaeology during the 1960s and 70s. This combined prehistory with the ethnographic present in a similar but more disciplined manner. Since then there has been a reaction. Trigger (1980) has complained about the tendency of his colleagues to treat the indigenous populations of North America as laboratory specimens, and Fabian’s book, Time and the Other, showed how anthropologists could equate geographical remoteness with antiquity, so that non-Western societies might be thought of as existing in a past (Fabian 1983).

In fact the word prehistory has been used in two quite different ways. So far this account has concentrated on the first of these and has discussed what is really a particular sub-discipline within archaeology. It refers to the research of a number of specialists and the assumptions that they bring to their task. The term can be used in another way which is less vulnerable to political abuse. Prehistory is not simply a synonym for the uncivilised or remote, it also describes a particular conception of time. The distinction is akin to that found in social anthropology where what were once called ‘primitive’ societies are now described as ‘traditional’.

Figure 1.1 | An Indian stone circle compared by Sir John Lubbock with prehistoric monuments in Europe. |

Source: from Lubbock (1870).

The difficulty with this new terminology is that it could easily misrepresent the nature of archaeological analysis. It may be true that particular communities were governed by oral lore, but if their conduct was guided entirely by unwritten traditions, they are not among the sources that can be studied by prehistorians, whose only evidence is that of material remains. If archaeologists are to engage with such people at all, it will be because their material culture can be treated in similar ways to the texts produced by other communities. If past societies are to be described as ‘traditional’, it must be because their artefacts, buildings and landscapes provide evidence for such traditions. Otherwise there is a risk of substituting one unsatisfactory term for another.

Telling the time

Traditions can only develop through the passage of time, and time, we might suppose, is the archaeologist’s medium. But it is generally taken for granted, and this leaves some important questions unanswered. Prehistorians have only recently considered this subject. Time, they claim, must not be treated separately from social life, for it is culturally constructed and must be understood in terms of local practices. Times are multiple and overlapping; there is no single strand to be followed from the past to the future. Gosden puts this point particularly well:

All action is timed action, which uses the imprint of the past to create an anticipation of the future. Together the body and material things form the flow of the past into the future. Human time flows on a number of levels. Each level represents a different aspect of the framework of reference. Long-term frames of reference are those within which we are socialised, made up of the particular shape of the landscape, historically special sets of relations between people and definite forms of interaction between people and the world…. Long-term systems of reference are contained within the shape of the cultural landscape…. Within this larger structure … are contained the more point-specific sorts of evidence deriving from short-term and specific acts.

(Gosden 1994: 17–18)

Time is part of the process of living in society. Just as no two societies are the same, there are many different ways in which time may be experienced and described.

In fact it may be only in modern industrial society that people measure time according to a single scale. That is because, under capitalism, time costs money. It is a feature which involves specific expenditure and can be portioned out like any other commodity that carries a financial value (Shanks and Tilley 1987: chapter 5). But in other contexts time may be experienced quite differently. It can be conceived according to many different scales. For instance, it may be related to the sequence of natural phenomena, like the lunar month and the annual cycle of the seasons. It may also refer to the passage of human generations, so that it is calibrated by the important events that punctuate the lives of individual people, like birth, initiation, maturity and death (Adam 1990; Gell 1992; Hughes and Trautman 1995). The possibilities are limitless.

If time can be experienced in different ways, even within the same society, it can also be studied at a number of different scales. One scheme was devised by the French historian, Braudel, who distinguished between the rapidly changing history of events, the medium term of economic cycles, and what he called the longue durée which relates mainly to demography and the natural environment (Braudel 1969). Each of these is reflected in an academic division of labour, so that political history is mainly concerned with the first of these time scales and economic history with the medium term. The longue durée has more influence on landscape history. It is a matter of choice which scale is most appropriate to the subject being studied. Gosden (1994) suggests that a similar division can be made in prehistoric archaeology, and he distinguishes between the day-to-day activities of people in the past, which were governed by habit, and the long term continuities expressed by monuments and similar structures which provide evidence of public time. It is one of the tasks of archaeologists to consider how these were related to one another in particular situations in the past.

If time is a social construction and can be conceptualised in so many different ways, how can it be studied by archaeologists? I find Gell’s book, The Anthropology of Time, especially helpful here. Gell (1992) distinguishes between two fundamentally different ways of thinking about time. Following earlier writers, he distinguishes between what he calls the A-series and the B-series. In the A-series, time is conceived in terms of three states – past, present and future – while the B-series distinguishes between events which exist ‘before’ or ‘after’ any particular moment.

The A-series is the subjective time experienced by human actors. As we have seen, there are numerous ways in which time is reckoned in non-Western societies and it is quite clear that the notion of an unbroken chain of events reaching into an infinite future is a peculiarly local way of perceiving duration, even if it is one to which modern industrial societies subscribe. In fact, time may be considered according to many different schemes, all of which fall within the A-series, and it is perfectly possible for it to be experienced on more than one level within the same society, according to the contexts in which it is most significant. In the same way, time can be experienced quite differently between the people in neighbouring communities. It follows that it is most unlikely that prehistoric groups experienced the passage of time in exactly the same ways as we do today. Their responses are likely to have been so varied that it will be difficult to interpret them now.

The B-series, on the other hand, plays a fundamental role in the sciences. It is universal and provides the basic measure to which all other schemes are related. Yet in Gell’s thesis the A-series and B-series are not alternatives to one another. Rather, the B-series describes a universal process on which ‘subjective time’ offers a commentary. Both kinds of time scheme need to be considered, but it is essential to retain some hold on ‘scientific time’ for it provides a common measure according to which other systems can be compared.

This scheme has an immediate relevance for prehistoric archaeology, for one of the main aims of prehistorians has been to establish an objective chronology for past events, using such basic methods as the analysis of stratigraphy and the application of absolute dating methods. Such processes have been fundamental to the creation of order among the material residues of the past. Moreover, those chronologies provide a framework within which quite different interpretations of the past can be considered. These may include the subjective understanding of time experienced by communities in prehistory, but that second approach may only rarely come within the competence of archaeologists.

It is easy to define the archaeological equivalent of the B-series. Unless archaeology can distinguish what came ‘before’ and ‘after’ particular events, it has no basis for proceeding, and it is that ability to define sequence on which much ...