![]() I

I

Experienced Cognition: Consciousness and Cognitive Skill![]()

1

Experienced Cognition and the Cospecification Hypothesis

No one really knows what consciousness is, what it does, or what function it serves.

—Johnson-Laird, 1983, p. 448

What should cause some fear, actually, is the idea of selfless cognition.

—Damasio, 1994, p. 100

Introduction

Consciousness and learning are central topics for psychology. Questions about how we experience and adapt to our environments—including the inner environment of the body and the social environments comprising other persons and artifacts—set the research agendas for a wide range of disciplines in the cognitive sciences. My purpose in writing this book is to describe a framework for thinking about consciousness and learning. The basis for this framework is what I call the cospecification hypothesis of consciousness, a hypothesis that is part of a cognitive, informational theory of what consciousness is and what it does. My hope is that this framework points the way toward understanding consciousness in a range of cognitive phenomena and toward developing a cognitive psychology that encompasses a scientific understanding of first-person perspectives, a cognitive psychology of persons.

I call this framework experienced cognition because that label captures the central themes I develop. First, I believe that successful cognitive theory must begin with, and account for, cognition as experienced by the individual. Consciousness is central to both the phenomena and explanations that make up the domain of cognitive theory. Second, I believe that understanding consciousness and cognition depends on understanding the changes that occur as we become experienced—as we learn and acquire cognitive skills. The ways in which we can be aware and the consequences of that awareness for our activities depend on our skills and change as we acquire increasing skill. In particular, studying the acquisition and performance of cognitive skills can provide insight into our conscious control of our activity. Finally, we experience our cognition as embodied and as situated in a variety of environments. Experienced cognition must therefore be understood in light of an ecological approach to psychology, an approach that emphasizes that persons are organisms acting in and on environments.

My intention is not to review the huge literature on consciousness (although that is a worthy goal, attempted with some success by Davies & Humphreys, 1993, and by Farthing, 1992). Instead I develop the experienced cognition framework on its own terms, borrowing from or comparing with other approaches as it seems useful. My perspective is that of an experimental cognitive psychologist. Cognitive psychology has generally been distinguished from the other cognitive sciences in part by its use of a level of description that is psychological in the traditional sense of corresponding to contents that are or could be part of conscious mental states. I agree with Natsoulas (1992, p. 364) that very often "consciousness is what psychologists actually examine" (Carlson, 1992). Some authors (e.g., Dennett, 1991) regard adopting this level of analysis as a mistake or temporary expedient. My opinion, which of course informs everything written in this book, is quite different. I believe that description of mental processes at the level of conscious mental states, and therefore theorizing at the level of lawful relations among such states, has a privileged status in the development of psychological theory. In my view, no psychological theory that fails to recognize consciousness as central to human cognition can claim to be comprehensive or correct.

Consciousness in Psychology and Cognitive Science

Cognitive scientists have made a great deal of progress in understanding many traditional issues concerning mental activity, but cognitive science has also received its share of criticism (e.g., Dreyfus, 1992; Harre & Gillett, 1994). In my view, the most important criticism of current cognitive science is that it lacks a compelling theory of consciousness and, thus, a means of linking persons and their experience to cognitive theory. Although some (e.g., Dennett, 1987) have argued that successful cognitive theories must be conceived at a subpersonal level, I believe that a cognitive theory that accommodates rather than explains away the existence of conscious, experiencing selves is both possible and desirable, a theme I return to in the final chapter.

The last decade or so has seen an enormous upswell of cognitive science literature on consciousness, by psychologists (e.g., Dulany, 1991; Umiltà & Moscovitch, 1994), philosophers (e.g., Dennett, 1991; Searle, 1992), linguists (e.g., Jackendoff, 1987), neuroscientists (e.g., Edelman, 1989) and neuropsychologists (e.g., Shallice, 1988), computer scientists (e.g., Minsky, 1986), and even physicists (e.g., Penrose, 1989). It has been some time now since consciousness was taboo in mainstream psychological journals although many psychologists still feel uneasy with the term consciousness (Natsoulas, 1992; Umiltà & Moscovitch, 1994). The scientific and philosophical literature on consciousness has grown to the point that it is impossible for any one scholar to read all that is written on the topic.

Despite all the energy and ink recently devoted to the topic of consciousness—and intending no slight to the thoughtful work of many researchers—I think it is fair to say that we do not have a plausible general theory of consciousness. In part, this is because there is not general agreement on either what is to be explained (automaticity? qualia?) or on what would constitute an explanation. Perhaps the most popular contemporary approach is to attempt to explain consciousness in biological or quasi-biological terms, to answer the question, "How could a brain—or a computer-simulated neural network—generate consciousness?" However, even a cursory review of the literature demonstrates the wide variety of current approaches.

The term consciousness itself has many senses (Natsoulas, 1983). Later in this chapter, I propose a specific hypothesis about consciousness that implies a particular view about the core concept of consciousness. It may be useful to offer at this point a preliminary sketch of that core concept as I see it. I am most concerned with that sense of consciousness that might be labeled primary awareness—the fundamental, unreflective experience of an individual experiencing and acting in an environment. Central to consciousness in this sense is the notion of subjectivity, of an experiencing self with a point of view. This is the sense of consciousness that has, in my opinion, been discussed least adequately by cognitive scientists and their precursors; as Searle (1992) noted, "It would be difficult to exaggerate the disastrous effects that the failure to come to terms with the subjectivity of consciousness has had on the philosophical and psychological work of the past half century" (p. 95). Understanding consciousness in this sense depends critically on the concept of self as agent, the idea of conscious control of mental and physical activity. Agency is the experience of oneself as an originator or controller of activity, and is central to understanding conscious experience.

Most discussions of consciousness or control in cognitive science are characterized by one of two stances—the implicit agent stance or the absent agent stance. In the implicit agent stance, the mind is characterized as a system controlled by an implicit agent sometimes referred to as the executive or just the subject, as in "the subject uses working memory (or semantic memory, or any other proposed cognitive system) to accomplish the task." This stance acknowledges subjectivity but fails to explain it or to really integrate it into theory. In the absent agent stance, the focus is entirely on information about the presumed objects of thought and control and agency are not discussed at all. The subject of sentences describing mental events becomes the brain, or the cognitive system, rather than the person whose mental events they are. I have more to say about how cognitive scientists have treated (or failed to treat) the subjectivity of consciousness in the next chapter.

Let me finish these introductory comments by emphasizing two additional points: First, consciousness is not a thing but a systemic, dynamic property or aspect of persons—typically engaged in purposive activity in an information-rich environment—and their mental states. Second, consciousness is not a special or extraordinary occurrence, but in fact is an utterly mundane aspect of human experience.

Consciousness and Cognitive Causality

Consciousness plays a central role in the causality of cognitive processes by serving to control mental and physical activity. This is of course not the only reason we value our conscious experience, but I believe that it is the key to understanding experienced cognition.

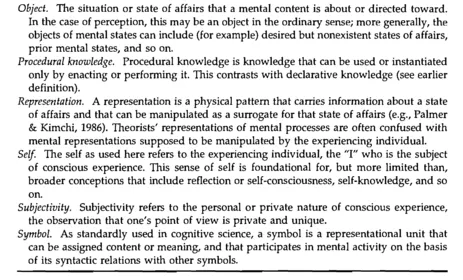

One of the major limitations of current accounts of consciousness is the failure to describe conscious states in terms of variables that link those states with theoretical descriptions of cognitive activity (an important exception is Dulany's work, e.g., 1991). Consciousness is thus described in intuitive terms, and a great deal of research effort has been spent in trying to show that some presumed process is unconscious and dissociable from conscious cognition (for a review, see Greenwald, 1992). Indeed, relatively casual claims that something is unconscious are much more frequent in the literature than are detailed analyses of any aspect of conscious thought. And, as with other proposed distinctions such as implicit and explicit memory, conscious and unconscious processes are often seen as activities of separate, dissociable systems. In contrast to this nonanalytic stance and the separate systems assumption (Dulany, 1991), I argue that describing the structure of consciousness in informational terms can provide variables for theoretical descriptions of cognitive activity (see Table 1.1).

At the core of my account of consciousness is that to be conscious is literally to have a point of view, which provides a here-and-now referent

for the spatial and temporal organization of cognitive activity. The central idea or intuition here is that the conscious, experiencing self functions as an agent in the cognitive control of activity. Understanding how that can be amounts to understanding cognition in terms that make essential reference to a first-person perspective.

Three Themes for Understanding Experienced Cognition

In my view, consciousness, learning, and an ecological perspective on cognition are inextricably linked. These topics thus serve as organizing themes for understanding experienced cognition. In this section, I describe the background and motivation for each of these themes.

Consciousness as Primary Awareness and Subjectivity

Consciousness in the sense of primary awareness is the critical starting point for theory because it is this sense that points to the experiencing self involved in controlling the flow of mental events. At one level of description, cognition can be described as a sequence of conscious mental states. Despite James' (1890) much-cited description of the "stream of consciousness," contemporary cognitive scientists have made relatively little explicit effort to understand cognition as a sequence of conscious, experienced mental states. The term mental state is meant to abstract from an individual's stream of experience and activity those units that in common sense we refer to as having a thought or seeing an object, units at a temporal scale from roughly a few tenths of a second to a few seconds. Each mental state may be described as the experience of some content from some point of view, a characterization elaborated in chapters 4 through 6. I assume that experienced cognition can be described at least approximately as a continuous series of such states, and in later chapters, I elaborate this assumption.

Many of the processes that properly concern cognitive scientists can, however, be appropriately described as cognitive but not conscious. Consider, for example, the process by which written language evokes comprehension. Some computational process must mediate this process (for no one would claim that such a process involves only the direct pickup of information), and that computational process must involve knowledge (for no one would argue that the ability to read particular words is innate). And although we do not (I believe!) read while we are unconscious, the relation between our visual awareness of the written word and our semantic awareness of its meaning calls for an explanation in terms other than a sequence of conscious mental states. To many cognitive scientists, such examples imply that consciousness is merely the tip of the iceberg of cognitive processing (e.g., Farthing, 1992) or even entirely epiphenomenal (e.g., Harnad, 1982; Jackendoff, 1987; Thagard, 1986}—in either case, it seems clear to many that these considerations imply a "cognitive unconscious" (Schachter, 1987) in many ways compatible with the personal unconscious postulated by Freud (Erdelyi, 1985). But understanding what such claims entail requires a theory of consciousness that has not yet been presented. Throughout this book, I use the term nonconscious to refer to informational (i.e., knowledge-bearing, thus cognitive) processes that cannot be understood on the model of conscious mental processes. I reserve the term unconscious for theoretical proposals that—like Freud's—assume that some mental states are like conscious ones (for example, having content or intentional structure; see chapters 4-5), but are not experienced in the sense that conscious states are. This usage is at odds with some current proposals (e.g., Marcel, 1983), but marks a distinction that I believe is important for understanding the implications of particular theoretical claims. Alternatively, it seems appropriate to describe persons as unconscious when they are deeply asleep or comatose (although dreaming might be an interesting intermediate case).

One clue to understanding the relation between consciousness and nonconscious cognitive processes is systematically distinguishing between content and noncontent properties of conscious mental states. The content of a conscious mental state corresponds to an answer to the question, What are you thinking? However, understanding the role in cognitive activity of a particular state may require that we consider other properties of the state such as its duration or repeatability, or the degree of activation or evocative power (Dulany, 1991) of its informational content. Such properties are of course not reportable, or may be reportable only as second-order judgments about the original state in question. In Part II, I describe a framework for characterizing mental states that allows us to to make this distinction in a principled way.

An Ecological Perspective on Cognition

Our everyday experience comprises primarily the experience of goal-directed activity in an information-rich environment. Consciousness is grounded in—and normally functions in the context of—purposeful, goal-directed action that is guided and supported by information currently available in the environment and picked up by the perceptual systems. To understand this experience thus requires an ecological perspective. In choosing the phrase ecological perspective, I am of course alluding to the work of James Gibson. Gibson (1966, 1979) saw his theory of visual perception as opposed to the information processing framework (and its predecessor, the unconscious inference view of perception), arguing that normal perception was not mediated by mental activity. This direct perception view has been elaborated by his followers (e.g., Mace, 1974), and has been the focus of much debate. In my opinion, however, the debate over the directness of perception (e.g., Fodor & Pylyshyn, 1981) has distracted attention from the most important insights embodied in Gibson's theory. It seems clear that there is a computational story to tell about the process by which proximal stimulation (e.g., events at the retina) plays a causal role in perception, and in this sense, perception is mediated rather than direct.

More important than Gibson's insistence on the directness of perce...