![]()

Part 1:

Compassion or competition

![]()

1

The Buddha and the banker

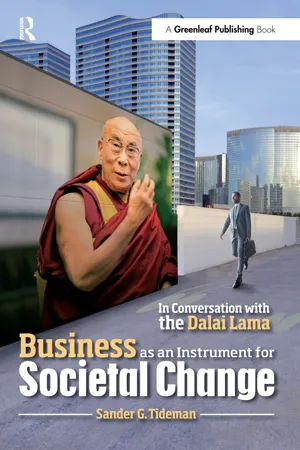

The author, his wife Sandra, and daughter Louise, visiting the Dalai Lama in 1991.

The connection between banking and the thinking of the Dalai Lama may seem at odds, and a career in finance combined with an interest in Buddhism unusual. This introductory chapter, therefore, describes my first meeting with the Dalai Lama and the impact this has had on my outlook and career. Ultimately, it awakened a sense of “purpose” in me at a time when my own and the wider world was entirely seduced by the benefits of economic growth.

After meeting the Dalai Lama, I chose to specialize my law studies in the emerging economies of Asia and then to become a banker in China, just when it had embraced drastic free-market reforms. As a bank manager in China, I not only handled exciting business opportunities in a booming market, I also explored the economic conditions in the disadvantaged regions of Tibet and Mongolia. These explorations led to further discussion with the Dalai Lama, ten years after my first meeting. After witnessing firsthand the Asian financial crisis in 1998 and the rise of excessive focus on short-term shareholder value in the financial industry, I became gradually disillusioned with mainstream banking and the larger system of capitalism, again turning to the Dalai Lama for guidance. The discussion that ensued became the first in a series of public dialogues with him, the theme of which was “Compassion or Competition.”

1.1 Meeting the Dalai Lama

In the summer of 1982, just before graduating from law school in the Netherlands and starting a career, I decided to prolong my worry-free student life with a study tour in India. Together with my student friend, Florens van Canstein, I ended up spending a few months in the Himalayas. As students of international law, we took a special interest in the Tibetan government-in-exile in Dharamsala, established by Tibetan refugees after China annexed their country in 1959. We had obtained an introduction to the Tibetans from Dr. Michael van Walt who was conducting a PhD at our university on the international legal status of Tibet. We met the leaders of the refugee community in Dharamsala in the Himalayan foothills, who shared with us grueling stories of the escape from their occupied homeland and their difficult life in exile. In one of these meetings, we befriended a Tibetan who arranged for an unexpected audience with His Holiness the Dalai Lama. He was much less known in the world before getting the Nobel Peace Prize in 1989, so receiving an audience was not as exceptional as it is now.

Nonetheless, I felt rather unprepared for this privilege, and felt nervous as we waited for what seemed a very long time in the waiting room of His Holiness’ house. It was a rather unpresumptuous one-floor building overlooking the valley, encompassed by a fragrant flower garden. However, when we entered his room, my nervousness miraculously disappeared. The Buddhist leader, who laughed while pointing to my half-cut Bermuda pants, quickly put me at ease: “What happened to your pants?” he quipped. I had no words to describe the custom of leaving the rough edges hanging after cutting off half of the pants, so I started to laugh too.

When we sat down, his gentle smile and intense gaze quickly captured me. His answers to questions that would now look terribly naïve and unin-formed have guided me throughout my life.

My first question centered on the issues between China and Tibet: “It seems to me that, ideologically speaking, there does not need to be conflict between China and Tibet. Marxism (at that time still China’s leading ideology) and Buddhism do not seem to be fundamentally opposed to each other. There must be something in common between these two systems. Why is there disagreement?”

The Dalai Lama answered at length. “I find certain aspects of Marxism most praiseworthy from an ethical point of view, principally in its treatment of material equality and the defense of the poor against the exploitation by a minority. I believe one might say that the economic system closestto Buddhism would be a socialist economic system. Marxism is based on noble ideas such as the defense of the rights of those who are disadvantaged. But the energy given to the application of these principles is rooted in a violent hatred for the ruling classes, and that hatred is channeled into class struggle and the destruction of the ruling class. Once the ruling class is eliminated, there is nothing left to offer the people and everyone is reduced to a state of poverty. Why is this so? Because there is a total absence of compassion for certain groups of people in Marxism. So that is the big difference with Buddhism, which promotes compassion and care for all people, both rich and poor.”

My next question concerned Eastern spirituality. I had seen many people in India, especially Tibetan refugees, who practiced spirituality and seemed so happy and content. They were smiling and singing in spite of the very harsh circumstances they faced in the temporary refugee camps. By contrast, I was leading a life of relative affluence but did not consider myself happy. How could that be?

His Holiness quickly unmasked my romantic notions about the East as misplaced disappointment with my own culture: “There is nothing that your culture lacks. Whether Eastern or Western, people are trying to be happy, seeking peace, living in harmony with the world. Maybe Western countries at this time have more economic wealth than in India or Tibet, but that does not make them different from people who have much less. Look at the recent demonstrations against a nuclear war in your country, in Europe. This is driven by the same wish for happiness and peace as we Tibetans. Basic human nature is the same; we are kind, peace-loving beings.”

Then the conversation turned to the role of anger in Buddhism. I thought about what had happened to the Tibetans and whether they would ever remove the Chinese from their land without violent effort. Was violence totally rejected? What about a parent trying to discipline unruly children?

The Dalai Lama replied: “Anger is a destructive emotion, with negative consequences for both the subject and object. But there are circumstances possible where forceful action is allowed, to make a point clear. But the important factor here is your motivation. A father being firm to his child is generally motivated by his compassion for the child. The same applies to the Tibetans: we can be firm and steadfast in the face of Chinese unjust policies out of compassion for them. If the motivation is just anger and frustration, you’d better be very careful about your behavior. The main problem with anger is that it destroys your peace of mind. You will be much more happy when you manage to transform these negative emotions into patience, love, and compassion. Compassion leads to happiness, for yourself and others.”

This exchange made a deep impression on me. It caused me to reflect on the choices we had made in the West that had enabled us to create material wealth, while at the same time forgetting the need to create social wealth—happiness. What could we learn from the East so that we would create a more balanced economy? And what could the East learn from the West, so that they could create more economic wealth? Perhaps most moving was the fact that His Holiness took me, a young and unimportant student in hippy pants, so seriously. He had given me his undivided attention, as if he saw more in me than I held possible for myself. It was the highlight of our journey through Asia that motivated me to start taking my own life and my own culture a bit more seriously.

It was the beginning of a quest for purpose: how can I make a difference in my life? As a student I had felt rather overwhelmed by the challenges in the world, but the unexpected meeting with the Dalai Lama had given me a glimpse of the possibilities in my life. The Zen Master D.T. Suzuki wrote: “Life as such has no meaning but you can give meaning to life.” I embarked on a journey to give my life meaning.

1.2 Encountering economic theory

Back at university after my return from India, when I enrolled in a course in economics, I could find little that corresponded to the remarks of the Dalai Lama. The economics textbooks talked of economic laws which assumed that man naturally competes for scarce and limited natural resources. As the founder of modern economics, Adam Smith said in The Wealth of Nations:

It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard of their won interest. We address not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities, but of their advantages.1

While this statement became the root of the powerful concept of the free market, it has been misconstrued by subsequent economists to imply that human beings are selfish by nature.

Classical economists tell you that it makes no sense to exert time, effort, and expense on maintaining values, if money can be made by ignoring them. In 1930, one of the great economists of the last century, Lord Keynes, wrote the following:

we must pretend to ourselves and to everyone else that fair is foul and foul is fair; for foul is useful and fair is not. Avarice and usury and precaution must be our gods for a little longer still. For only they can lead us out of the tunnel of economic necessity into daylight.2

In Keynesian thought, which exerted a powerful influence on economists for much of the last century, ethical considerations are not merely irrelevant; they are actually a hindrance.

In one of my first classes I was told that the theory of economics was built on the image of the Homo economicus, defined as someone who is rational, individualistic, and driven by a desire for maximum utility, i.e., the optimal satisfaction of his needs. Since I hardly knew of anyone who would totally fit this description, I raised my arm to question the logic of the assumption. The answer, which I later heard many economists repeat, was revealing: “In economics we need the premise of the Homo economicus as a theoretical construct in order to make the overall economic logic work. And since this works so well, I suggest you just accept it so that we can move on.”

I realized much later that it was these very assumptions that caused economics to be called a “dismal science,” more based on theory than reality.3

Economic theory, which considered itself a science of human economic behavior, had left human psychology and other social sciences outside its spectrum. It was based on the belief that people behaved rationally and that happiness was maximized by consumption and monetary wealth—an assumption that is contradicted by the social sciences. After my trip to Asia, I found it particularly difficult to reconcile this assumption with the happy faces I had seen in desolate Tibetan refugee camps.

1.3 Finding purpose in economic development

In spite of my misgivings regarding the theory of classical economics, I was drawn to its application. In India—with its overwhelming levels of poverty—and the Tibetan refugee community, I had witnessed what results when there is no functioning economy or enterprise sector. Moreover, my journey through Asia had made me realize that countries initially thought of in the West as third-world countries—especially Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Singapore—had quite unexpectedly generated considerable wealth through opening up their economies for international trade and investment. They were no longer regarded as third-world nations but rather “newly industrialized countries,” or more exotically “Asian Tigers,” on their way to becoming members of the first world. If the third world can become the first world just by reforming economic policy, I should try to understand what this entails. What was the secret to creating wealth? Was there an economic model possible that would create both financial and social wealth? That could create both money and happiness?

These questions led me to focus my studies on international economic law with a focus on Asia. This inspired me: for the first time in my life I had a sense of purpose. I had no idea what it would lead to, but I felt I was on the path to making a difference. Following my studies in Holland, I spent a year at the University of London at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) and London School of Economics (LSE), studying the legal and economic systems of the newly industrialized countries of Asia, especially China. In the mid-1980s this giant country—considered a member of the second world along with all socialist countries—was recovering from the harsh and introverted Mao era, and started to experiment with the market economy. It seemed as if we were finally growing into one “first” world.

The more I understood of the changes happening in China, the keener I became to actually work and live there. After completing my studies in London, I left for Taiwan to study the Chinese language. After one year of full immersion in the language and culture, and fascinated by the dynamics of this “Asian Tiger” economy, I took up a job as an intern at Baker & McKenzie, an international law firm with offices all over the world, including Taipei, where the Chinese lawyers welcomed this “long nose” (as they called foreigners) to help them with their growing number of international clients. Even though my role was small, as the only European in the office it was a great opportunity to observe the expanding international trade flows moving to Asia. Before long, I was called into meetings with Western firms to advise them on the law of the Republic of China, the formal name of Taiwan, which they had retained since “losing the mainland” to the communists in 1949.

1.4 Becoming a banker in China

After about two years as an aspirant lawyer working between continents, in 1989 a Taiwan-based manager of ABN AMRO Bank—the largest bank in the Netherlands—called and told me that the bank was looking for someone to manage and expand business in China. The candidate should be a Chinese-speaking Dutchman with a good understanding of business and economics. He said, “You may not know it, but you are the ideal candidate.” I had never aspired to a career in banking and, since I was training to be a business lawyer, I could hardly see myself as a bank manager. But it did not take long for me to realize that this presented a tremendous opportunity to develop myself professionally and personally in the most exciting region at that time, as China’s mainland was opening its huge market to the world. At the same time, it would enable me to explore more deeply the question lurking in the back of my mind since meeting the Dalai Lama: is it possible to create an economy that creates both economic and social wealth?

My banking career had begun. In the summer of 1990, I was appointed the bank’s representative in Beijing. As country director for China, I was responsible for business development in this large emerging economic region. My job was to establish partnerships with Chinese banks and companies, and with Sino–foreign joint venture companies, and open up representative offices in major Chinese cities. Through that network I was to find projects that needed funds from the international capital markets.

It turned out to be a fascinating time in history, in which China started to embrace elements of Western capitalism. While the Tiananmen incident in 1989—the crackdown by the Chinese military on massive student protesters who were calling for democracy—was still fresh in the memory, the Chinese leadership had started opening up the economy to foreign trade and investment. It was a time of rapid change and innovation, which gave me a crash course in global capitalism and economics.

Within a few years, the Chinese landscape transformed completely. The majority of the population shifted from wearing Mao suits to wearing Western-style clothes. Traditional houses and Soviet-type apartment blocks gave way to impressive skyscrapers and office buildings, while agricultural land was transformed into industrial zones with manufacturing facilities and four-lane highways that were the products of foreign investment. I vividly remember a meeting with the mayor of Shanghai, who from his office pointed to a huge area of barren land across the River Pu with the words: “That land will become China’s new financial center.” I could not believe it. It felt like what bankers call a...