![]()

Part 1

The Character of Towns

![]()

Chapter 1

The Common Qualities of Traditional Towns

Planned Origins

Until the 20th century, the United States had a long history of founding settlements according to certain organizing principles. That conscious planning is evidenced by the large number of surviving original drawings (many reproduced in John Reps’s The Making of Urban America) and by countless examples of formal rectilinear street patterns for small towns and boroughs that one may find in many 19th century county atlases (see also Easterling 1993).

Even in New England, famed for irregular street layouts, many villages are arranged around a central common or green, a feature that was not accidental even when the green occupied only a widened segment of a main street. After their founding, settlements that had been laid out in a grid tended to follow that same pattern in succeeding decades because it was practical, economical, and customary. This practice continued in many areas until the advent of the mid-20th century suburb, which was enabled and propelled by widespread car ownership, and then when zoning replaced traditional physical planning in most communities (Jackson 1985), often with regrettable results in terms of community form.

Diverse Uses within a Common Design Vocabulary

With the demise of conscious planning of streets and neighborhoods came a new emphasis on separating dissimilar land uses. The goal of creating separate and internally homogeneous “zoning districts” took precedence over the established traditions of town development that had produced such interesting and livable communities. Few planners critically examined the future implications of the physical form of the new style of development (subdivisions, shopping centers, and office parks), which were typically disconnected from each other and totally dependent on cars. Zoning was seen as the modern way to prevent urban ills from recurring in the new suburbs. Many planners became so focused on promoting zoning that they overlooked and neglected older, more traditional ways of creating communities and failed to foresee the extent of sprawl, which was propelled by new interstate highways that served as “can openers” to develop the countryside.

Although towns were more orderly during the 19th century, with regular street patterns and harmonious buildings (due to a limited architectural vocabulary, simpler technologies, and fewer choices of building material), they tended to be more diverse in another way—with a richer mixture of uses than is typically the case in areas developed within the last several decades. Community design evolved spontaneously over time, without codes or regulations. Changes occurred in response to specific and varying stimuli, such as local job growth and public sanitation improvements. The sections of older towns that predate zoning are far from perfect, but they generally functioned very well, especially considering they grew up without oversight or control from professional regulators.

Distinguishing Features

The principal characteristics of traditional towns include the following:

- compactness and tighter form (compared with typical suburban zoning)

- medium density (between that of cities and postwar suburbs)

- “downtown” centers with street-edge buildings, mixed uses, gathering places, public buildings, parks, and other open spaces

- commercial premises that meet everyday needs (grocery, drug, and hardware stores)

- residential neighborhoods close to the town center, sometimes with house lots abutting commercial premises

- civic open spaces within and rural open space at edges

- pedestrian-friendly and auto-accessible design

- streets scaled for typical uses (rather than being oversized and overengineered to accommodate “worstcase scenarios”)

- incremental growth outward from their core

Traditional towns are not without problems, of course. Residential sections may experience some annoyances because house lots sometimes back up to different land uses, such as a filling station with tires or dumpsters stored behind a building. Or there may be a pizzeria or convenience store down the street that attracts late-night traffic. House lots often tend to be modest, with minimal front or side yards. Streets are often narrow, constricted by parked cars. Although parks and greenways are frequently underprovided, such towns are usually very livable.

Sense of Community

Many residents live within easy walking distance of typical amenities such as schools, shops, churches, and playgrounds. They often feel an attachment to their neighborhood and a sense of place about their street, where they know many of their neighbors. When queried about what they like about living in a traditional town, the same factors are mentioned time and again—the variety, convenience, and neighborliness typical of life in such places.

Clearly, many people like the mixture of larger and smaller homes mirroring the diversity of the community’s families and individuals of all ages, from young couples to elderly widows; house lots of varying widths and sizes; and connecting streets that link homes with other neighborhoods, shops, and public facilities. One resident’s characterization of Cranbury, New Jersey, summed it up: “It is [this] pleasant and useful mix . .. that fosters a pedestrian lifestyle which, in turn, gives residents a strong sense of community” (Houstoun 1988).

Three advantages of small-town living are noted by James Rouse, the innovative developer of Columbia, Maryland (Breckenfeld 1971):

- the greater likelihood of a broader range of relationships and friendships

- an increased sense of mutual responsibility and support among neighbors

- a closer relationship to nature through informal outdoor recreation opportunities

The results of the 2013 Community Preference Survey, commissioned by the National Association of Realtors, revealed that smaller yards were desired by the majority of respondents (by 11 to 21 percentage points) when they are in locations that require shorter commutes and are in walking distance of schools, shops, restaurants, and parks. Nearly 80 percent of respondents said that when buying a home, they look for neighborhoods with good schools, abundant sidewalks, and other pedestrian-friendly features. Also, while house size remains important, many buyers would manage with less square footage if that would enable them to spend less time behind the wheel. Specifically, 59 percent would opt for a smaller home if their commuting time could be cut by 20 minutes. Another interesting finding is that 88 percent of respondents said they put more value on the quality of the neighborhood than on the size of the house (National Association of Realtors 2013).

From this research as well as from anecdotal evidence, it is clear that many people yearn for the attributes offered by traditional towns and for the open space that typically surrounded them. Although people generally do not aspire to live in a seamless web of sprawling subdivisions, shopping centers, and office parks, that is the ultimate future being provided for them and their children by the current planning system in the vast majority of jurisdictions (with assistance from engineers, developers, land-use lawyers, and realtors, most of whom uncritically accept the standard suburban approach to community growth).

Opportunities for Casual Socializing

In The Great Good Place, Ray Oldenburg underscores the importance of typical small-town gathering places (such as coffee shops, general stores, post offices, bars, and other hangouts) in helping people “get through the day.” A critical missing element in today’s North American suburbs is what Oldenburg terms “the third place”: settings where informal public life occurs other than one’s home or workplace. “Third places” rarely occur in suburbia, where people build family rooms “so their children may have a decent place to spend time with their friends” within subdivisions “that offer them nothing” (Oldenburg 1989). Gathering places, from neighborhood parks to cafes, are noticeably absent from most modern suburbs. Some of these places have been zoned out, and some (such as local parks or open spaces) are no longer being created by developers or municipalities. Because most developers have experience creating only single use neighborhoods with little or no open space, strong and clear regulations are often necessary to break the current mold.

Open Space within and Around

Another favored aspect of traditional small towns, especially those located in rural areas and along the metro edge, is the open space within them (scattered parcels of undeveloped land throughout the community) and on their outskirts. Although most people take these spaces for granted, they are strongly affected when open space is developed with buildings and parking lots. Few things change the character of small towns and rural communities more than the conversion of these natural areas to developed properties. Whether appreciated for their aesthetic, recreational, or wildlife benefits, such areas often hold deep meaning for residents.

Perhaps not surprisingly, these places often produce profound effects on people who played in them as children. When asked to write “environmental autobiographies” describing a favorite childhood place, 80 to 90 percent of Clare Cooper-Marcus’s students at the University of California at Berkeley cited “wild or leftover places . . . that were never specifically designed. . . . If they grew up in a developing suburb they remember the one lot at the end of the street that wasn’t yet built upon, where they constructed camps and dug tunnels and lit fires” (Cooper-Marcus 1986). Criticizing planners for failing to understand the importance of such natural areas, Cooper-Marcus notes that “it is just those wild leftover or unassigned spaces that we tend to plan out of existence.”

Compact Form and Incremental Growth

Towns have been growing and evolving since colonial times, but until the mid-20th century, changes tended to be gradual and generally reflected customary patterns of town layout and structure. Any differences occurred chiefly in newer building styles. In other words, the town’s preexisting grain was respected (perhaps unconsciously) by subsequent development designers.

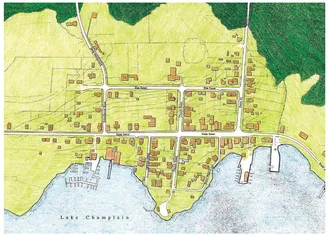

An almost pristine example of such a town is Essex, New York, located on the western shore of Lake Champlain. Once an active port and regional trading center, Essex began to stagnate after 1850, as many small subsistence farming families moved westward. Because of its relatively remote northern location and the decline in its local economy, few changes occurred in the town fabric, and the place remains a bit of a time capsule. A current plan of the town clearly shows the scale and pattern of the house lots, the relation between commercial and residential uses, and the interconnectedness of the street layout (see Figure 1-1). This is one of thousands of communities where traditional town building values have created a very livable and walkable environment. (A photograph of an Essex streetscape appears in chapter 4 as Figure 4-11.)

However, it should be noted that the development approach taken in older communities was not always without fault. For example, in many cases before environmental factors were fully appreciated, communities were laid out and developed with little regard to wetlands and natural drainages. Not only did such plans create awkward situations (and sometimes real problems) for future generations to deal with, but they also missed opportunities to create municipal amenities such as linear park systems, which would have enhanced the quality of life for future residents, as illustrated in the lowa City example in Figure 10–20.

Figure 1-1: Above is the plan of the small 19th century village of Essex, New York, showing typical arrangements of buildings, setbacks, lot size variety, and interconnected rectilinear streets. Such places appeal to a large number of people, yet very few new developments are designed to look, feel, and function like traditional towns. Ironically, today it is illegal in many places to create subdivisions with these characteristics, even though they would utilize land more efficiently, allow significant parts of the site to remain as open space, and provide opportunities for more social interaction among citizens. In Figure 10–20, the town plat from Iowa City, lowa, laid out by country surveyors in 1839, shows how little the natural drainage pattern was considered when streets and blocks were drawn. This practice was typical for more than a century. (Source: Roger Trancik, FASLA)

Figure 1-2 offers a magnified view of a typical compact neighborhood from another such town (Brunswick, Maine), dating from a slightly later period (1870–1910). This sketch was drawn by local architect Steven Moore, who notes, “The street has a very pleasant ambience and a delightful scale. The houses are generally two-and threestory wood frame buildings. About half the homes have been divided into multiple rental units or accessory apartments, yielding a density of approximately 20–25 persons per acre” (e-mail from Steven Moore, October 14, 2014).

Although this density is greater than might feel comfortable in some small towns, the ability of such neighborhoods to easily ...