- 332 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book addresses contemporary geographical issues in the Mediterranean Basin from a perspective that recognizes the physical characteristics and cultural interactions which link the different Mediterranean states as a recognisable geographic entity. Sixteen chapters each deal with a major geographical issue currently facing the Mediterranean, each providing an invaluable summary of the extensive but widely dispersed literature relating to Mediterranean issues. Particular emphasis is placed on the interaction between society and environment in terms of environmental management, differential regional development and its associated political, demographic, cultural and economic tensions.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Mediterranean by Russell King,Lindsay Proudfoot,Bernard Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

INTRODUCTION: AN ESSAY ON MEDITERRANEANISM

AIMS AND SCOPE OF THE BOOK

This book aims to be the first university-level text on the geography of the Mediterranean. Such a claim needs some justification, and perhaps a little qualification. First, one can point with some confidence to the paucity of geographical literature that treats the Mediterranean as a relatively homogenous regional unit. The problem here is that the traditional continental or sub-continental divisions of regional geography textbooks cut through the Mediterranean, so that bits of the Basin appear in books on Europe, Africa or the Middle East. Yet it is clear that on physical, cultural and historical criteria the Mediterranean presents itself as a more unified region than either Europe or Africa. Between these the real boundary is the Sahara Desert, which has been a more effective barrier to contact than the Mediterranean which, rather, has acted as a focus for communications and interaction.

Second, it should be stressed that this book addresses contemporary geographical issues in the Mediterranean Basin from a perspective that recognises the importance of both physical environmental characteristics and historical-cultural legacies. Indeed, it is the multi-layered interactions between physical, cultural and contemporary social and economic geographies which define the essence of the Mediterranean landscape and Mediterranean life, and which make the littoral regions of the Mediterranean states cohere as a recognisable geographical entity. The nature of these interactions will be explored in a little more detail towards the end of this chapter, and they will recur at various points throughout the book.

Third, we must recognise what has been published. There is undoubtedly a vast geographical literature on the region or, rather, on various areas and localities within the region. This literature is scattered in journals published in many countries and in many languages – including Japanese! Moreover, given the characteristic interdependence of physical, cultural and economic criteria in defining the essence of the region and its problems, the interest of the Mediterranean geographer also extends to literature in a range of other disciplines such as geology, ecology, archaeology, history, anthropology, economics and political science. But the quantity of literature on the Mediterranean Basin as a whole, or as a distinct ecological or geographical unit, remains curiously limited. At the textbook level, and limiting ourselves for the time being to geographical studies published in English, those that exist are either very old and hence hopelessly out-of-date (Newbigin 1924; Semple 1932); or they are too elementary to be regarded as serious university texts (Branigan and Jarrett 1975; Robinson 1970; Walker 1965); or they only treat certain parts of the basin such as southern Europe (Beckinsale and Beckinsale 1975; Hadjimichalis 1987; Hudson and Lewis 1985; Williams 1984) or certain themes such as urbanisation (Leontidou 1990), rural landscapes (Houston 1964) and mountain environments (McNeill 1992).

The above brief listing by no means exhausts the geographical library on the Mediterranean. Amongst other books of an earlier generation mention should be made of W.G. East’s Mediterranean Problems (1940), an early essay on geopolitics, and André Siegfried’s The Mediterranean (1949), translated from the French. Pride of place amongst French studies goes to Birot and Dresch’s two-volume survey on the Mediterranean and the Middle East (1953, 1956). Perhaps the most rounded geographical survey of the region is that by Orlando Ribeiro, available both in the original Portuguese and in an updated version in Italian (Ribeiro 1968, 1983).

Yet, perversely, the two most important books on the Mediterranean are written by non-geographers. One looks back to the sixteenth century (Braudel 1972, 1973), the other forward to the twenty-first (Grenon and Batisse 1989). Fernand Braudel’s tour deforce is the classic that all Mediterranean writing must pay homage to; almost any book on the region is destined to be enriched with quotes from the great French ‘geo-historian’. Grenon and Batisse look to the future of the Mediterranean. Their book is the ‘Blue Plan’ scenario (or set of scenarios), the UNESCO economic and social planning initiative concerned with the coastal regions of the Mediterranean that examines the environmental and natural resource problems common to all or most countries of the region. The Blue Plan will itself make many appearances in the pages that follow.

The present volume attempts what none of the others achieve: a complete and integrated treatment of the various systematic geographies of the Mediterranean Basin, treating the whole region both as a unity and a diversity, and stressing the physical-human interactions which lie at the heart of a full geographical understanding of the area. The substantive contents of the book consist of sixteen synoptic chapters, each dealing with one of the major geographical issues or themes of the Mediterranean, plus the introductory and concluding chapters. Each contributor provides an expert synthesis of recent important work relating to their topic, informed by their own perspectives and research. This combination of primary research with invaluable summaries of the extensive but widely dispersed journal and other literature enables the book to fulfil two important objectives: to make an original contribution in its own right; and to enable its readers to attain a thorough understanding of the Mediterranean region and its problems.

DEFINITION OF THE MEDITERRANEAN

To define the Mediterranean is not an easy task. In some senses it is probably a pointless exercise, for there is no single criterion which enables one to draw a line on a map which separates the Mediterranean from the non-Mediterranean. Mediterranean identity is a more nebulous, but powerful, concept that derives from environmental characteristics, cultural features and, above all, from the spatial interactions between the two. The Mediterranean is a sea, a climate, a landscape, a way of life – all of these and much more.

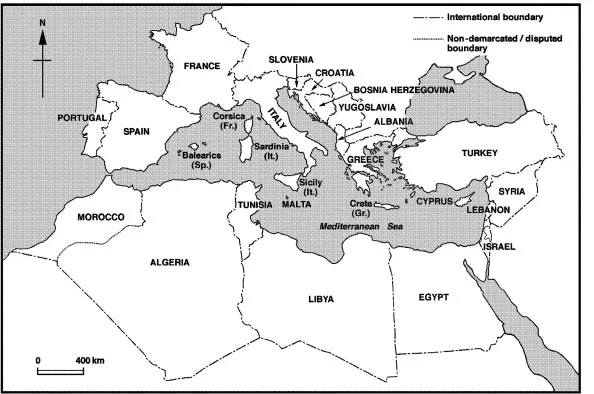

Various authors have defined the region arbitrarily, pragmatically, and not very satisfactorily. All three elementary geographies of the Mediterranean (Branigan and Jarrett 1975; Robinson 1970; Walker 1965) employ the definition ‘the countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea’. But many of these countries extend to other, non-Mediterranean regions: France to northern Europe, Algeria to the Sahara, Egypt to the middle Nile and Syria to Mesopotamia. The break-up of Yugoslavia has produced states with variable links to the Mediterranean: Croatia has the island-studded Dalmatian coast; Slovenia, whilst claiming to be ‘on the sunny side of the Alps’, has a tiny foothold on the sea itself; Serbia looks more to the Danubian Plains. And then there is Portugal, Mediterranean in climate and culture, with no Mediterranean shore. Others cast the net even wider. In their discussion of Mediterranean demography Montanari and Cortese (1993) embrace Jordan and Iraq and also make out a case for Bulgaria, Romania and Georgia to be included. Figure 1.1 shows how these various countries stretch the limits of the Mediterranean region.

FIGURE 1.1 Countries around the Mediterranean

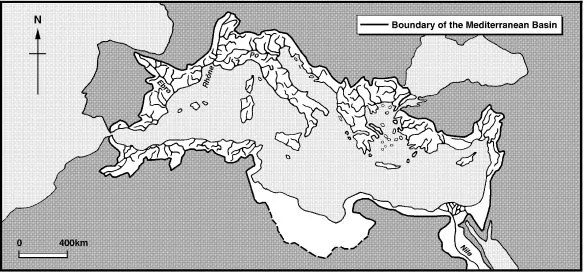

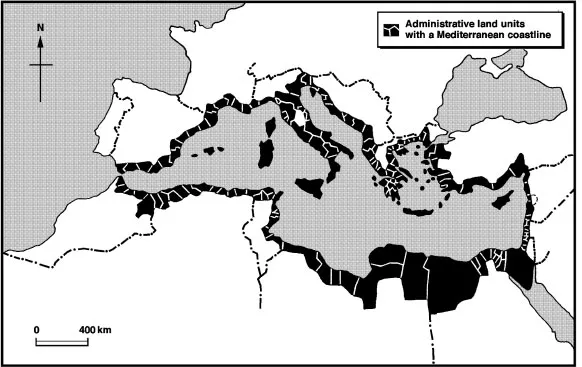

Much narrower definitions are proposed by the Blue Plan team. Their view is of an area ‘where socio-economic activities are governed largely by their relations with the seaboard’ (Grenon and Batisse 1989, pp. 15–16). This reflects the Blue Plan’s overriding concern with the sea and with coastal processes such as tourism, urbanisation and water shortage. The ‘proximity to the sea’ definition is presented in two variants, one based on physical criteria and one on administrative units. The hydrological basin (Fig. 1.2) is proposed as the most suitable boundary of study for all matters relating to fresh water, including land-based pollution from rivers: this recognises that the Mediterranean impact of rivers such as the Rhône or the Po may originate in non-Mediterranean regions. The idea of a ‘coastal zone’ depends greatly on local coastal topography as well as on the nature of the phenomenon being studied. Hence the hemmed-in coasts of the French and Italian Rivieras contrast with the featureless coastal wastes of parts of Egypt and Libya; and coastal-strip tourism contrasts with the orientation of transport networks. For strictly practical reasons to do with the availability of population and economic data, the Blue Plan opted to employ the coastal administrative divisions of each nation bordering on the Mediterranean Sea (Fig. 1.3). This produces a strip of variable width depending on the size of units used, with marked variation both between countries (e.g. Tunisia and Italy) and within countries (e.g. Egypt). Only the island-states of Malta and Cyprus are delineated as wholly Mediterranean by this method; and of the larger countries only Italy and Greece succeed in having the majority of their areas included.

FIGURE 1.2 The Mediterranean watershed

Source: Grenon and Batisse (1989, p. 19)

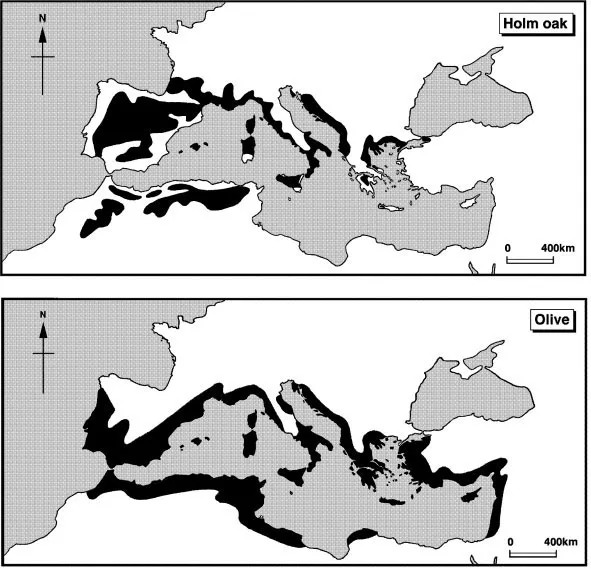

Perhaps a more fruitful approach (literally!) to defining the Mediterranean is through bio-geography, explored in depth in Chapter 16. Figure 1.4 shows the distribution of four key plants of the region. The climax plant of the Mediterranean forest is the holm oak but this extends to Aquitaine in south-west France and misses out the eastern shores of the basin. More indicative of the Mediterranean environment is the olive, for the summer drought which is the essential feature of the Mediterranean climate is essential for the build-up of oil in the fruit, whilst the deeply penetrating roots can find moisture in even the most rugged of limestone soils. With trees that endure for centuries, the olive (Fig. 1.5) is a symbol of cultural stability and provides the basis of the Mediterranean diet. Hence it lies at the nexus of Mediterranean culture and environment. Some would say it is the Mediterranean.

But we should not forget that there are several other characteristically Mediterranean plants. The Aleppo pine has a distribution quite akin to that of the olive (Fig. 1.4). The maquis – the characteristic Mediterranean scrub woodland – has a wide variety of plants which are adapted in various ways to the summer drought and to the fires which are its constant scourge (Tomaselli 1977). Moving to cultivars, the vine is very widespread in the region but is not diagnostic of the Mediterranean, being cultivated as far north as the Rhine valley and even southern Britain. More coterminous with the olive are other Mediterranean tree-crops such as the fig, the carob and the pistachio, whose fruits once had great meaning to local peasant economies.

These, and the other species mentioned, both singly and in their intercropped associations, continue to embody key elements of the visible Mediterranean landscape. In saying this we are moving towards an appreciation, if not a proper definition, of the Mediterranean as an experience rather than as some kind of objectified ‘reality’ to be portrayed on a map. Of all the geographers who have written on the region, J.M. Houston comes closest to this artistic appreciation of the Mediterranean when he states that the geographer must approach the landscape as a painter would (Houston 1964, p. 706). The colour, light and ‘atmosphere’ of the Mediterranean have long drawn artists and writers whose work constitutes the final channel by which geographers can define the essence of the region. For Lawrence Durrell, author of two marvellous books on Corfu and Cyprus (Durrell 1956, 1962), the Mediterranean ‘is landscape-dominated; its people are simply the landscape-wishes of the earth sharing their particularities with the wine and the food, the sunlight and the sea’. Symbols of this landscape are ‘the familiar prospects of vines, olives, cypresses … the odour of thyme bruised by the hoofs of the sheep on the sun-drunk hills’. Never content when living away from the wine-drinking countries of the Mediterranean, Durrell yearned always to return to ‘the mainstream of meridional hospitality where a drink refused was an insult given … such laughter, such sunburned faces, such copious potations’ (Durrell 1969, pp. 356–7, 369–71).

FIGURE 1.3 Administrative regions bordering the Mediterranean

Source: Grenon and Batisse (1989, p. 18)

This book considers it inappropriate to define the Mediterranean in any hard and fast way. In general, its contributors focus on the Mediterranean littoral and on those areas characterised most closely by Mediterranean environment and culture. However, where common sense (or the availability of statistical data) dictates, a broader definition will be applied, as in the chapters on geopolitics (Chapter 8), economic development (Chapter 9) and demography (Chapter 11), where trends derive as much from national (or international) scale variables as from local processes.

FIGURE 1.4 The limits of four Mediterranean plants

Source: Partly after Grenon and Batisse (1989, p. 8)

MEDITERRANEANISM

The writings of Lawrence Durrell are but one example of a literary approach to understanding what is the essence of the Mediterranean – what one may call Mediterraneanism. One of the qualities of Mediterraneanism is undoubtedly the close in...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 Introduction: An Essay on Mediterraneanism Russell King

- Chapter 2 Geological Evolution of the Mediterranean Basin Alastair Ruffell

- Chapter 3 Mediterranean Climate Allen Perry

- Chapter 4 Earth Surface Processes in the Mediterranean Helen Rendell

- Chapter 5 The Graeco-Roman Mediterranean Lindsay Proudfoot

- Chapter 6 The Mediterranean in the Medieval and Renaissance World

- Chapter 7 The Ottoman Mediterranean and its Transformation, ca. 1800–1920

- Chapter 8 Politics and Society in the Mediterranean Basin Nurit Kliot

- Chapter 9 Mediterranean Economies: The Dynamics of Uneven Development

- Chapter 10 The European Union’s Mediterranean Policy: From Pragmatism to Partnership

- Chapter 11 Population Growth: An Avoidable Crisis? Russell King

- Chapter 12 Five Narratives for the Mediterranean City Lila Leontidou

- Chapter 13 The Modernisation of Mediterranean Agriculture

- Chapter 14 Tourism and Uneven Development in the Mediterranean Allan Williams

- Chapter 15 Water: A Critical Resource Bernard Smith

- Chapter 16 Forests, Soils and the Threat of Desertification

- Chapter 17 Coastal Zone Management George Dardis and Bernard Smith

- Chapter 18 Conclusion: From the Past to the Future of the Mediterranean

- Index