![]()

Part 1

THE END OF THE USSR AND THE CREATION OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION

![]()

Chapter 1

Gorbachev, perestroika and the end of soviet socialism

Learning objectives

To examine why Mikhail Gorbachev launched

perestroika.

To examine Gorbachev’s political, economic and foreign policy reforms.

To examine the role of national identities in the demise of the USSR.

To examine the August 1991 coup and the end of soviet socialism.

Introduction

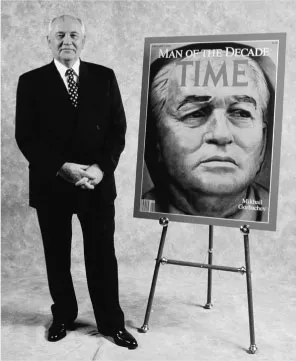

In March 1985 Mikhail Gorbachev became general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), the leader of the USSR. He launched a ‘revolution from above’ called perestroika or reconstruction, designed to revitalise soviet socialism. Perestroika entailed radical changes in political, economic, social and foreign policies which were supposed to be mutually complementary. ‘Gorbymania’ spread throughout the world so that in 1987 he was American Time magazine’s ‘Man of the Year’ and in 1990 he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. In contrast to this adulation, within the USSR perestroika was condemned by ideological hardliners as the abandonment of soviet socialism and by radicals as just tinkering with an economically, politically and morally bankrupt system. The reforms rapidly gained a momentum of their own. Gorbachev lost control over his revolution as the soviet people turned it into a ‘revolution from below’, making increasingly radical demands that ran far ahead of Gorbachev’s more modest reforms. Even some members of the soviet nomenklatura, such as Boris Yeltsin, started to renounce soviet socialism in favour of western-style democracy and the market. There was a hopelessly botched hard-line coup attempt in August 1991 but the reform genie could neither be put back into the bottle nor satisfied by Gorbachev’s reforms. By December 1991 Gorbachev, who had set out to reform and thereby strengthen the USSR, had unwittingly overseen the demise of the soviet empire in east-central Europe (in 1989), the end of soviet socialism, and the disintegration of the USSR into 15 independent states and was himself out of office.

Box 1.1 Mikhail Gorbachev (1931–)

Gorbachev was born in Privolnoi a village in the Stavropol region of South Russia. The son of a tractor driver he joined the Communist Youth League (Komsomol) in 1945 and the CPSU in 1952. From 1950–55 he studied law at Moscow State University. On graduation Gorbachev returned to Stavropol where he worked for the Komsomol and then the CPSU staff (apparatus). In 1971 he became a full member of the CPSU Central Committee and in 1978 became the CPSU secretary for agriculture. In 1979 he became first a candidate and then in 1980 a full member of the CPSU Politburo. In 1979 Gorbachev was elected to the USSR Supreme Soviet and in 1980 to the RSFSR parliament. He was elected general secretary of the CPSU in March 1985 and was reelected to the post in July 1990. In 1988 he was elected chair of the Supreme Soviet Presidium and in March 1990 the Congress of People’s Deputies elected him the first executive president of the USSR.

Mikhail Gorbachev and Time magazine cover.

In August 1991 Gorbachev and his family were held under house arrest at their holiday home in Foros during an attempted coup; they were released by Yeltsin and his allies. On his return to Moscow Gorbachev found the USSR disintegrating and political developments dominated by Yeltsin. He stood in the 1996 Russian presidential elections but received only 0.5 per cent of the vote.

Gorbachev’s publications include: Perestroika, Nottingham: Spokesman, 2nd edn, 1988; Memoirs, London: Bantam Books, 1997; The August Coup: The Truth and the Lessons, London: HarperCollins, 1991.

Useful website: Gorbachev Foundation http://www.gorby.ru/en/default.asp

Why did Gorbachev launch perestroika?

Gorbachev’s explanation

Gorbachev advocated perestroika to eradicate the stagnation or zastoi that was the legacy of Leonid Brezhnev’s long tenure as leader of the USSR from 1964 to 1982. According to Gorbachev, the soviet people had become inert and lacking in initiative, crime rates were rising, corruption was pervasive, labour indiscipline was rife, and drunkenness and alcoholism were endemic. The CPSU was itself culpable as it had lost touch with the people and had not fulfilled its constitutionally prescribed ‘leading and guiding role’. Party bureaucrats, who were neither subjected to appropriate party discipline nor democratic oversight by the people and the media, had been able to reduce previous reform attempts to ineffective campaigns and empty slogans. In 1983 two future Gorbachev advisers, the economist Abel Aganbegyan and the sociologist Tatyana Zaslavskaya, produced the ‘Novosibirsk Report’ (Hanson, 1984) chronicling the precipitous decline of the soviet economy. They argued that the methods used by Stalin to turn the USSR from a backward agricultural country into a great industrial and military power were no longer appropriate. The centrally planned economy (CPE) and the whole soviet command-administrative system needed radical reform.

Gorbachev described perestroika as ‘a genuine revolution’ in all aspects of soviet life and as a ‘thorough going renewal’ (Pravda, 28 January 1987). This did not mean he took office with a clear strategy: although problem areas had been identified, actual solutions were slower to emerge. During 1985–6 there was a lot of discussion about the need for perestroika and some new slogans were adopted such as calls for ‘acceleration’ (uskorenie) in the economy, but there were few concrete achievements. Attempts to streamline the bureaucracy through the creation of new super-ministries, such as Gosagroprom for agriculture, in reality only added yet another layer of bureaucracy. A new policy of ‘openness’ or glasnost was introduced into the media and the arts in order to expose the scale of the USSR’s problems and to persuade the people to support and participate actively in perestroika. Gorbachev resurrected his predecessor Andropov’s anti-corruption and discipline campaigns, adding an anti-alcohol campaign. Now dubbed the mineral water secretary (mineral'nyi sekretar'), Gorbachev seemed to be trying to make the old system work by cleaning and sobering it up. His renewal of party-state bureaucrats or cadres, again a resurrection of Andropov’s purge of corrupt and inefficient bureaucrats, also looked like the typical move of a new leader eager to demote opponents and promote allies. In 1987, spurred on by the USSR’s escalating problems, Gorbachev launched his radical reforms.

The legitimacy of CPSU rule was supposed to be based upon the ideology of Marxism-Leninism, but Brezhnev had been aware that while ideological exhortations were not unimportant they were not enough to sustain the regime. He had instituted an unwritten social contract between the people and the party, according to which the people had economic security (such as guaranteed work and cheap food) and in return they were expected to be politically pliant. Not all soviet citizens were prepared to abide by this ‘contract’ and from the 1960s onwards dissident voices challenged the very legitimacy of the soviet system. However, writing in 1980 the dissident soviet historian Roy Medvedev cautioned that, ‘The overwhelming majority of the population unquestionably sanction the government’s power and show no particular wish to have a run-in with the authorities by voicing their grievances’ (Medvedev, 1980: 36). When dissent did emerge the soviet state responded with harassment and force.

Gorbachev was committed to reducing the level of state coercion within the USSR and he also realised that, in the short term at least, economic perestroika would lead to unemployment and a fall in real incomes. Perestroika simultaneously broke the social contract and weakened the state’s ability to put down the resulting growing discontent. Gorbachev had to develop new mechanisms to persuade the soviet people to support the regime and perestroika; he had to overcome the cynicism, suspicion and, for some, fear that the prospect of reform generated. Gorbachev believed that democratisation would foster a sense of responsibility among the people for their own and the leadership’s actions, and that the soviet leadership at all levels would be accountable to the people so combating elite inefficiency, ineptitude and corruption. Gorbachev recognised that although he was the CPSU general secretary, supposedly the most powerful man in the USSR, reform entailed confronting vested interests whether in the form of workers or party-state bureaucrats (Zaslavskaya, 1988). In order to reform the economy and maintain a (reformed) soviet socialism, democratisation was imperative.

Ideology: a set of core principles or ideas.

Marxism-Leninism: the official state ideology of the USSR drawing on the ideas of the German philosopher and economist Karl Marx (1818–1883) and Lenin (1870–1924) the leader of the Bolsheviks, whose real name was Vladimir Ilych Ulyanov. It includes the Marxist ideas that human labour determines economic value; that struggle between classes (such as workers versus the capitalists) is the motor of social change; and that history progresses through stages towards the final stage of communism in which class exploitation no longer exists and so a state is no longer required. Leninism is the application of Marx’s ideas to Russian conditions and the policies advocated by Lenin; these include: the communist party as a revolutionary elite, his theory of Imperialism and concept of Peaceful Coexistence.

Useful website: Marxist Writers’ Archive http://www.marxists.org/archive/

Soviet socialism: the form of socialism developed in the USSR during the 1920s and 1930s with some later modifications. Its features include a one-party state, Marxism-Leninism as the official ideology, a rejection of political pluralism, state or collective ownership of the means of production, central planning of the economy (CPE) through a series of five-year plans which were disseminated by commands down the administrative system, also known as the ‘command administrative system’.

Nomenklatura: often used as shorthand for the soviet elite. The nomenklatura were the people occupying the most important posts in the party, state and economic bureaucracies or apparatuses. The CPSU controlled the selection of the nomenklatura, whose existence was well-known but its operation was shrouded in secrecy.

The systemic and structural problems of the soviet economy

The USSR had a centrally planned economy (CPE) with state or collective ownership of enterprises and farms. In the 1920s and 1930s the USSR was electrified, new coal mines were dug, and dams, railways, new steel mills and gigantic heavy industrial centres were constructed. The CPE proved adept at promoting this extensive economic growth by increasing the inputs of labour, energy and materials directed to these sectors. This economic system achieved growth at tremendous human and ecological costs, and created an economy that was structurally skewed towards heavy industry and mineral extraction. From the 1950s light industry, the consumer sector and agriculture received more investment but still remained hopelessly underdeveloped. By the 1950s the old stress on gigantic factories and the military rhetoric of ‘storming the steel front’ was no longer appropriate, but reform proved elusive.

Writing in 1966 Alec Nove, an economist at Glasgow University, argued that the USSR was experiencing a slowdown in growth because the soviet system could not cope with a mature economy, but he still anticipated substantial growth. The USSR needed to move away from its overdependence on the old smoke stack industries and to embrace the technological revolution that was sweeping the advanced capitalist economies. The CPE was less adept at promoting this intensive economic growth which required improving the quality, rather than just the quantity, of inputs. The CPE system also suffered from a lack of reliable data, rigid and unresponsive plans, and a general problem of providing incentives. The USSR needed to harness its people’s skills by encouraging them to show initiative and by improving their motivation, and it also needed new managerial techniques and new technologies such as computers and electronics. By the 1970s and 1980s most commentators in the west agreed that the Soviet economy was experiencing major problems but few anticipated an economic collapse. A notable exception was the economist Igor Birman (1983, 1989; Birman and Clarke, 1985) who emigrated from the USSR in 1974 and then published extremely gloomy analyses of the soviet economy. According to the British Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm it was already too late and that, ‘Almost certainly the Soviet economy was unreformable by the 1980s. If there were real chances of reforming it in the 1960s they were sabotaged by the self-interests of a nomenklatura that was by this time firmly entrenched and uncontrollable. Possibly the last real chance of reform was in the years after Stalin’s death’ (Hobsbawm, 2005: 21).

Since the 1960s Gorbachev’s predecessors had talked about reforming the CPE and restructuring the economy but had achieved little. The logic of reforming a CPE demanded the introduction of some form of decentralisation of decision making away from the State Planning Agency (Gosplan) and the ministries in Moscow. In Czechoslovakia during the 1960s, economic reforms which entailed the devolution of some limited decision-making authority had quickly spread over into popular demands for greater politi...