![]()

Chapter 1

Intimations of Memory and Thought

John F. Kihlstrom

Yak University

Victor A. Shames

University of Arizona

Jennifer Dorfman

University of Memphis

Poe dismissed the methods of both Bacon and Aristotle as the paths to certain knowledge. He argued for a third method to knowledge which he called imagination; we now call it intuition. . . . [Intuition.] lets the classification start so that the successive iterations, back and forth between the empirical and the rational, hone the product until it eventually conforms to nature. . . . Simply start, and like Poe, trust in the imagination.

—Allan Sandage and John Bedke

Cambridge Atlas of Galaxies, 1994

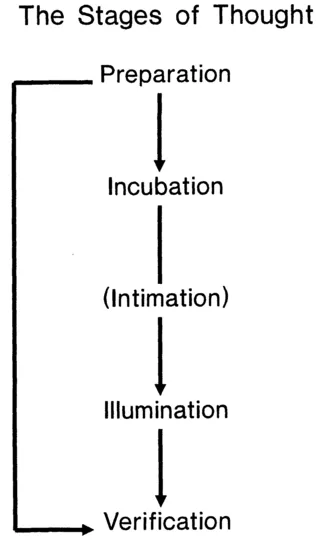

In The Art of Thought, Wallas (1926) decomposed human problem solving into a series of discrete stages, depicted in Fig. 1.1. In the preparation stage, the thinker accumulates declarative and procedural knowledge within the domain of the problem. Preparation requires awareness that there is a problem to be solved; it entails the adoption of a problem-solving attitude, and the deliberate analysis of the problem itself. Sometimes, the thinker solves the problem at this point. This is especially the case, Wallas thought, with what we would now call routine problems, in which the systematic application of a well-known algorithm will eventually produce the correct solution. If so, the thinker moves immediately from preparation to the verification stage, in which the provisional solution is confirmed and refined or discovered to be incorrect after all.1

At other times, however, the deliberate cognitive effort deployed during the preparation stage fails, and the thinker falls short of solving the problem.

FIG. 1.1. The stages of thought. Adapted from Wallas (1926).

Under these circumstances, Wallas (1926) argued that thinkers often switch to an incubation stage, in which deliberate, conscious problem-solving activity is suspended. The thinker may shift his or her attention to some other problem, or take a break and not think of any problem at all. In either case, Wallas believed, problem-solving activity continued at or beyond the fringes of consciousness. That this was the case was demonstrated (at least to Wallas's satisfaction) by the fact that the incubation period often ends in a "flash" of insight in which the solution to the problem suddenly appears in the consciousness of the thinker. This newfound insight is then subject to verification, just as before. As Wallas described it:

The Incubation stage covers two different things, of which the first is the negative fact that during Incubation we do not voluntarily or consciously think on a particular problem, and the second is the positive fact that a series of unconscious and involuntary (or foreconscious and forevoluntary) mental events may take place during that period, (p. 86)

* * *

[T]he final "flash," or "click" ... is the culmination of a successful train of association, which may have lasted for an appreciable time, and which has probably been preceded by a series of tentative and unsuccessful trains, (pp. 93-94)

* * *

[T]he evidence seems to show that both the unsuccessful trains of association, which might have led to the "flash" of success, and the final and successful train are normally either unconscious, or take place (with "risings" and "fallings" of consciousness as success seems to approach or retire), in that periphery or "fringe" of consciousness which surrounds the disk of full luminosity, (p. 94)

The risings of consciousness as success seems to approach: Wallas was quite clear that, during the incubation stage at least (and, for that matter, perhaps during the preparation stage as well), there comes a time when the thinker knows that the solution is forthcoming, even though he or she does not know what that solution is. He used the term intimation to refer to: "that moment in the Illumination stage when our fringe-consciousness of an association-train is in the state of rising consciousness which indicates that the fully conscious flash of success is coming" (p. 97). In other words, Wallas's intimations are intuitions (Bowers, 1984, 1994; Bowers, Farvolden, & Mermigis, 1995).

Intuitions, in turn, are a special form of metacognition (Flavell, 1979; Nelson & Narens, 1994; for reviews, see Metcalfe & Shimamura, 1994; Nelson, 1992). Metacognitions reflect people's knowledge or beliefs about their cognitive states and processes. In the context of problem solving, they are exemplified by feelings of warmth (FOWs; Newell, Simon, & Shaw, 1962/1979), where thinkers believe they are close to a solution, even though they are not aware of what that solution is. In the context of remembering, they are exemplified by feelings of knowing (FOKs; Hart, 1965), where rememberers believe that they know something, even though they are not aware of what they know.

In this chapter, we draw attention to some parallels between FOWs and FOKs on the one hand, and implicit memory on the other. In implicit memory, the person's experience, thought, and action is affected by past events which he or she cannot consciously remember (Graf & Schacter, 1985; for reviews, see Graf & Masson, 1993; Lewandowki, Dunn, & Kirsner, 1989; Roediger & McDermott, 1993; Schacter, 1987, 1995). Similarly, in FOWs and FOKs, the person's experience, thought, and action is affected by the solutions to problems which he or she has not yet consciously solved, or by knowledge which he or she has not yet consciously retrieved. In the remainder of this chapter, we argue that these intimations of memory and thought—FOKs and FOWs—share underlying mechanisms with implicit memory—or, at least, can have their origins in a priming process that is something like implicit memory.2

Intimations of Thought

The role played by intuitions in problem solving is admittedly controversial. Newell and Simon (1973), in their work on the General Problem Solver, suggested that intuitions, in the form of FOWs, are produced by a representation in short-term memory of the distance between the problem solver's current state and the ultimate goal state. In a series of studies, however, Metcalfe (1986a, 1986b; Metcalfe & Wiebe, 1987) found that FOWs are not necessarily accurate predictors of problem-solving success. Specifically, Metcalfe has argued that FOWs are accurate when problems are solved by memory retrieval, inasmuch as they reflect the gradual accumulation of problem-relevant information; but they are not accurate, and may even be misleading, when problems are solved by insight, inasmuch as insight requires restructuring the problem itself. Nevertheless, it does not seem that the two categories of problems—those that are solved by memory retrieval and those that are solved by restructuring—are mutually exclusive. In any event, it is clear that problems which can be solved by memory retrieval can still generate the "Aha!" experience that is the phenomenological essence of insight (Simon, 1986/1989).

Consider a particular type of word problem popularized by Mednick (1962; Mednick & Mednick, 1967) in the Remote Associates Test (RAT). The subject is presented with a set of three words, and the problem is to come up with a fourth word that is an associate of all three. A popular example is:

Democrat

Girl

Favor,

to which the solution is party. Smith (1995) has proposed a simple algorithm for solving RAT items:

- select a test word;

- retrieve an associate to that test word;

- select a second test word;

test whether the associate retrieved in Step 2 is also an associate of the test word selected in Step 3;

if so, proceed to Step 5;

if not, return to Step 1;

- select the third test word;

test whether the associate retrieved in Step 2 is also an associate of the test word selected in Step 5;

if so, that associate is the solution;

if not, return to Step 1.

A process like this does not have much of the character of an insight problem: It looks more like a matter of pure, brute-force memory retrieval. In fact, however, when people address RAT problems, they often have the "Aha!" experience as they achieve insight into the problem and its solution. If they do not achieve the solution on their own, then they may well have an "Aha!" experience when someone else tells them what the solution is. Both forms of "getting it" have the qualities of insight.

For present purposes, however, it is more important to note that people also have intuitions about these problems, in advance of their solution. Bowers and his colleagues (Bowers et al., 1995; Bowers, Regehr, Balthazard, & Parker, 1990) have developed a variant of the RAT called the Dyads of Triads (DOT) test, in which subjects are presented with two RAT-like items, one of which (the coherent item) is soluble, the other (the incoherent item) not:

| Playing | Still | |

| Credit | Pages | |

| (Card) | Report | Music | (none) |

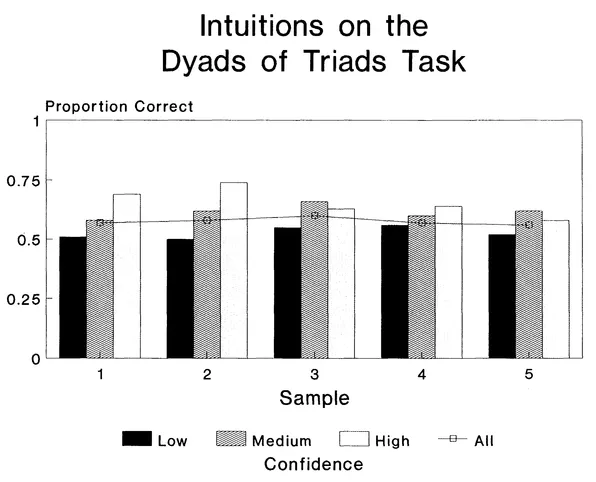

Subjects are asked to inspect the items and generate the answer to the coherent one; if they fail to do so, they are asked to indicate which triad is, in fact, soluble. Bowers et al. (1990) found that subjects are able to distinguish coherent from incoherent triads at better than chance levels, even though they are not able to solve the coherent triad. Figure 1.2 presents the results from five different samples of subjects who went through this procedure. The unsolved DOT items are classified in terms of the subjects' confidence that their choices were correct. In each sample, overall, the choices were correct significantly more often than would be expected by chance. This was especially the case when subjects were at least moderately confident of their choices.

It is of interest to note that Bowers et al. (1990) distinguished between two types of coherent triads. In semantically convergent triads, such as:

| Goat | |

| Pass | |

| Green | (Mountain) |

the solution word preserves a single meaning across the three elements. In semantically divergent triads, such as:

| Strike | |

| Same | |

| Tennis | (Match), |

the solution word has a different meaning in association with each element. Interestingly, the accuracy with which subjects can identify coherent triads is greater for convergent than for divergent ones.

FIG. 1.2. Accuracy of classification of RAT items in the DOT test, by confidence level. Chance performance = .5. Adapted from Bowers et al. (1990).

Bowers et al. (1990; see also Bowers et al., 1995) suggested that these intuitions in problem solving reflect the automatic activation (Anderson, 1983) of knowledge stored in semantic memory—in other words, they suggested that intuitions were based on priming effects similar to those familiar in the study of implicit memory. In this respect, the proposal of Bowers et al. picks up on an earlier suggestion by Yaniv and Meyer (1987) that priming lies at the bottom of another metacognitive phenomenon, FOKs in semantic memory.

Yaniv and Meyer (1987) presented subjects with the definitions of uncommon words, and asked them to generate the word itself:

Large Bright Colored Handkerchief; Brightly Colored Square of Silk Material with Red or Yellow Spots, Usually Worn Around the Neck.

If the subjects could produce an answer, they were as...