- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The African American Voice in U.S. Foreign Policy Since World War II

About this book

Following World War II, America was witness to two great struggles. The first was on

the international front and involved the fight for freedom around the globe, as millions

of people in Asia and Africa rose up to throw off their European colonial masters. In

the decades following 1945 dozens of new nations joined the ranks of independent

countries. Following the Civil War, the African-American voice in U.S. foreign affairs

continued to grow. In the late nineteenth century, a few African-Americans — such as

Frederick Douglass — even served as U.S. diplomats to the "black republics" of Liberia

and Haiti. When America began its overseas thrust during the 1890s, African-American

opinion was divided.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The African American Voice in U.S. Foreign Policy Since World War II by Michael L. Krenn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

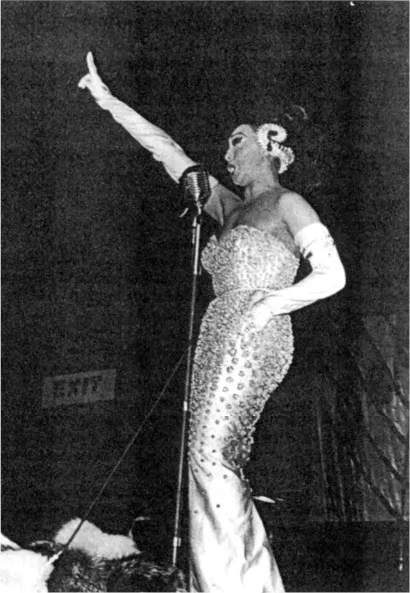

Josephine Baker, Racial Protest, and the Cold War

During the early 1950s, Josephine Baker was an international star who lived in a castle in France, who wore Dior gowns in concert, and whose most radical political idea seems to have been a hope that the world might some day live in racial harmony She would hardly seem a threat to the national security of the United States. Nevertheless, during the early fifties, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) kept a file on Baker, and the State Department collected data on her activities, using the information to dissuade other countries from allowing her to perform. Baker was seen as a threat because she used her international prominence to call attention to the discriminatory racial practices of the United States, her native land, when she traveled throughout the world.

Baker was caught in the cross fire of the Cold War in Latin America in the early 1950s. Her seemingly simple campaign for racial tolerance made her the target of a campaign that ultimately pushed her from the limelight of the exclusive club circuit to the bright lights of a Cuban interrogation room. The woman lauded in Havana and Miami in 1951 as an international star was arrested by the Cuban military police two years later as a suspected Communist, but she had undergone no radical political transformation in the interim. That Josephine Baker engendered an international campaign to mute her impact is a demonstration of the lengths to which the United States and its allies would go to silence Cold War critics. More important, however, Josephine Baker found herself at the center of a critical cultural and ideological weak point in American Cold War diplomacy: the intersection of race and Cold War foreign relations.1

In the years following World War II, the United States had an image problem. Gunnar Myrdal called it an “American dilemma.” On one hand, the United States claimed that democracy was superior to communism as a form of government, particularly in its protection of individual rights and liberties; on the other hand, the nation practiced pervasive race discrimination. Voting was central to democratic government, for example, yet African Americans were systematically disenfranchised in the South. Such racism was not the nation’s private shame. During the postwar years, other countries paid increasing attention to race discrimination in the United States. Voting rights abuses, lynchings, school segregation, and antimiscegenation laws were discussed at length in newspapers around the world, and the international media continually questioned whether race discrimination made American democracy a hypocrisy. When Sen. Glen Taylor was arrested for violating Alabama segregation laws, for example, the Shanghai Ta Kung Pao found a lesson for international politics: the incident did not demonstrate the moral leadership that would be required in a true world leader. “The United States prides itself on its liberal traditions,’” the paper noted, “and it is in the United States itself that these traditions can best be demonstrated.”2

To raise the stakes even higher, as early as 1946 the American Embassy in Moscow reported that several articles on American racial problems had been published in the Soviet media, possibly signaling more prominent use of the issue in Soviet propaganda. The Soviet Union and the Communist press in various nations used the race issue very effectively in anti-American propaganda. Meanwhile, allies of the United States quietly commented that Soviet propaganda on race was uniquely effective because there was so much truth to it.3

United States government officials were concerned about the effect of this international criticism on foreign relations. As Secretary of State Dean Acheson put it,

The existence of discrimination against minority groups in this country has an adverse effect upon our relations with other countries. We are reminded over and over by some foreign newspapers and spokesmen, that our treatment of various minorities leaves much to be desired. … Frequently we find it next to impossible to formulate a satisfactory answer to our critics in other countries.…

Josephine Baker performing at a benefit concert for the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW) at the National Guard Armory, Washington, D.C., July 2, 1951.

Photograph by Fred Harris. Courtesy Bethune Museum and Archives, Washington, D.C.

Photograph by Fred Harris. Courtesy Bethune Museum and Archives, Washington, D.C.

An atmosphere of suspicion and resentment in a country over the way a minority is being treated in the United States is a formidable obstacle to the development of mutual understanding and trust between the two countries. We will have better international relations when these reasons for suspicion and resentment have been removed.

Concern about the impact of race discrimination on foreign relations permeated government-sponsored civil rights efforts in the late 1940s and early 1950s. The international implications of civil rights were continually noted in briefs in the United States Supreme Court and in government reports.4

In this environment, African Americans who criticized race discrimination in the United States before an international audience added fuel to an already troublesome fire. When the actor and singer Paul Robeson, the writer W. E. B. Du Bois, and others spoke out abroad about American racial problems, they angered government officials because the officials saw them as exacerbating an already difficult problem. The State Department could and did attempt to counter the influence of such critics on international opinion by sending speakers around the world who would say the right things about American race relations. The “right thing” to say was, yes, there were racial problems in the United States, but it was through democratic processes (not communism) that optimal social change for African Americans would occur. It would make things so much easier, however, if the troublemakers stayed home. Consequently, in the early 1950s, the passports of Robeson, Du Bois, and Civil Rights Congress chairperson William Patterson were confiscated because their travel abroad was “contrary to the best interests of the United States.”5

Entertainer Josephine Baker posed a special problem for the government. During her international concert tours in the 1950s, she harshly criticized American racism. The United States government could not restrict her travel by withdrawing her passport because she carried the passport of her adopted nation, France. The government had to employ more creative means to silence her.

Josephine Baker is best known as the young black entertainer from St. Louis, Missouri, who took Paris by storm in the 1920s. In France there was great interest in African art and in jazz during the twenties, and, to French audiences, Baker seemed to embody the primitive sexual energy of black art and music that would energize European culture.6

The primary roles available for black entertainers in the United States at this time were heavily racially stereotyped. In France, Baker also had to cater to white fantasies about race. In the black review that brought her to Paris at the age of nineteen in 1925, Baker danced in a number called “Danse Sauvage,” set in an African jungle. In her opening performance at the Folies Bergère the next year, Baker did the Charleston dressed only in a skirt of bananas, a costume that would become her trademark. Eventually, however, Baker was able to transcend racial stereotyping in France and to play the music halls descending long staircases in elegant gowns in the kind of role previously reserved for white stars.7

Baker’s glamorous life in Paris was a stark contrast to her early years in St. Louis. Her family had been so poor that she and her brother would search for coal that had fallen off a conveyor belt in the freight yards in order to heat their home. For a time, the family of six slept in one bed. At the age of eight, Baker became a live-in housekeeper for a woman who beat her and made her sleep in the basement with a dog. She gained an early love for the theater, perhaps because it was an escape from the difficulties of her young life. She later explained that she danced to keep warm.8

Racism shaped Baker’s early memories. When interviewed in 1973 by young Henry Louis Gates, Jr., about her life, Baker began with memories of the 1917 race riots, which occurred when she was eleven years of age. The East Saint Louis riots were violent and deadly, and in her autobiography Baker described atrocities she witnessed as she fled the burning city. Yet the riots occurred in East Saint Louis, across the Mississippi River from Baker’s own home. The stories of the riots were seared in Baker’s memory; so horrified was she that she remembered the riots as if she had been there herself.9

In Paris, Baker was generally free of the day-to-day insults of American-style racism. She lived a glamorous life-style free from racial segregation. Like many other African Americans, she found the city a haven in the years between the two world wars. In 1937, after marrying a Frenchman, Baker finally adopted her new nation by becoming a citizen of France.10

Early in Baker’s professional life, her energies were focused primarily on the theater and on developing herself as a star. Her emphasis changed in 1939 when France declared war on Germany. Using contacts she had in the Italian embassy, Baker began doing intelligence work for the Allies and spending much of her time with refugees from the war. Adolf Hitler’s forces occupied Paris in 1940. Knowing that black entertainers would be unable to work in occupied France and fearing Nazi racism, Baker fled to the south of France and, ultimately, to North Africa. While still in France she joined the Resistance and, using her performance tours through Europe as a cover, participated in relaying information on Axis troop movements to the Allies. She wrote information in invisible ink on her musical scores and then passed on the scores. Later in North Africa she was hospitalized for nineteen months with peritonitis; only barely recovered, she found the energy to perform for Allied troops. For her work for the Resistance, Baker was awarded the Cross of Lorraine by Charles de Gaulle in 1943, and in 1961 she was awarded the Legion of Honor and the Croix de Guerre in recognition of her wartime service to France. Baker’s war work was in part motivated by her loyalty to her adopted country; at least as important, in fighting Nazism she was fighting racism. The struggle against racism and a search for universal racial harmony would be a driving force in her life in later years.11

In 1948, Josephine Baker sailed to New York, hoping to gain the recognition in the country of her birth that she had achieved in France. She had returned to the United States to appear in the Ziegfeld Follies in 1935 but had received devastating reviews. In 1948 as well, she did not find the critical acclaim she had hoped for; what she did find was racial discrimination. She and her white husband, Jo Bouillon, were refused service by thirty-six New York hotels. Baker then decided to see for herself what life was like for an average African-American woman in the South. Leaving her husband behind, she traveled south using a different name, and she wrote for a French magazine about such experiences as getting thrown out of white waiting rooms at railroad stations. Becoming Josephine Baker again, she gave a speech at Fisk University, an African-American school in Tennessee, and she told the audience that her visit to Fisk was the first time since she had come to the United States that she felt at home. After this trip, she told a friend that she would dedicate her life to helping her people.12

In 1950 and 1951, Baker scheduled a tour of Latin American countries but made no plans to visit the United States. She was a smash hit in Cuba; agents and club operators in the United States then became interested in booking her. She declined their invitations, saying she was not interested in performing in theaters with racially segregated audiences. In December 1950, she received a telegram in Havana from a New York agent who offered her a “tremendous” salary for an engagement at the Copa City Club in Miami Beach. She asked an American newspaperman, “What is Copa City and what is its policy concerning Negroes?” He told her that it was probably the most luxurious nightclub in the c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Half Title

- American Negroes and U.S. Foreign Policy: 1937–1967

- American Black Leaders: The Response to Colonialism and the Cold War, 1943–1953

- Black Critics of Colonialism and the Cold War

- Evolution of the Black Foreign Policy Constituency

- The Cold War: Its Impact on the Black Liberation Struggle Within the United States — Parts I and II

- Josephine Baker, Racial Protest, and the Cold War

- Ralph Bunche and Afro-American Participation in Decolonization

- From Hope to Disillusion: African Americans, the United Nations, and the Struggle for Human Rights, 1944–1947

- Hands Across the Water: Afro-American Lawyers and the Decolonization of Southern Africa

- The Civil-Rights Movement and American Foreign Policy

- Martin Luther King, Jr. and the War in Vietnam

- Blacks and the Vietnam War

- Acknowledgments