![]() Part One

Part One

The Internal Family Systems MetaModel![]()

1

The Essence of Emotional Healing

I assume that each person who enters my treatment office is seeking psychological healing. Each child, each parent, and each sibling carries emotional burdens and seeks relief from sadness, fear, shame, and feelings of inadequacy. Yes, even those children who protest being there, parents who say that they are too busy to participate, or kids who externalize the blame onto other family members are looking to be healed. Even those who are developmentally disabled and unable to represent their thoughts in easily discernible ways seek healing. All who enter seek to release emotional pain and to bring their Self-energy to both their inner and relational worlds.

Psychotherapy is a very powerful process. This book is about deep emotional healing for children and their families through applying a MetaModel, the Internal Family Systems (IFS) Model to children, their parents, and siblings. I will put forward a way of thinking, a conceptual map, to guide the clinician who works with child-focused problems. This conceptual map will be enhanced by presenting therapeutic applications of the IFS MetaModel.

The essence of psychological healing with children is to depathologize them. These children are referred to us by parents, teachers, pediatricians, and the legal system. We are expected to treat their “problems”—defiance, aggression, depression, anxiety, peer difficulties, addictions, somatization, etc., as would a medical practitioner treat a virus or a broken leg. The child has not asked to come to our office. A person in authority, usually a parent, has brought the child to us to be “fixed.” Often, by the time a child has come to see us, he has been referred for psychological or educational evaluations, special education, medical workups, and so on, resulting in feelings of being inadequate, “bad,” a disappointment to his parents, a problem in the classroom, ostracized by peers, and so on.

We will need to see potential where hopelessness has set in. We will need to see goodness when those connected to the child view him as a “problem.” We will need to see strengths. Most of all, we will need to understand that his symptoms are attempts at psychological survival. Whether the child is aggressive or withdrawn, internalizing or externalizing, noncompliant or pseudomature, we will need to put his symptoms in context—family, school, neighborhood, and internal emotional environment—and see that he is trying to cope with trauma, from mild to severe, resulting in insecure Attachment, anxiety, sadness, shame, and feelings of inadequacy.

Instead of a medically oriented diagnosis, the centerpiece of this model will be The Functional Hypothesis: childhood symptomatology is an attempt by the child to cope within a context that is emotionally traumatizing. The symptoms are attempts at psychological survival. These survival strategies work in the short run, but when overemployed will generate new problems that make life even more difficult for the child and family.

Ana, age six, was referred to me because of frequent tantrums with her mother. In my initial consultation meeting with her mother, Blanche, I learned that the parents had been divorced for two years, following a tumultuous history that included the father’s severe alcohol binges and physical abuse of Blanche, witnessed by Ana. The father’s second marriage is on shaky ground. Ana’s stepmother is a supportive figure. Currently, the father is in jail, awaiting trial for assault and robbery. Blanche’s father died several years ago from complications of alcoholism. Her mother has become frail in recent years. Blanche is working full time, requiring child care and after-school programs for Ana. Blanche looked exhausted. She expressed her concerns for Ana in a very loving manner. She wanted me to reduce Ana’s tantrums.

I told her I was hopeful that in a collaborative therapy with her and Ana, we would do this. When I asked her whether she would want help in not becoming so frustrated and powerless in her parenting, she replied warily, “I don’t know if that would be possible, but I’d like your help with that.”

Next I met Ana and her mother together. Ana made an immediate connection to me. Some confusion on her face about coming to a therapist dissolved into relief as I asked and learned about her strengths—she is smart, verbal, artistic, and strong-willed. She was trying very hard to show me that she is happy, however, her face looked tired and sad. When I gently asked about mother-daughter issues, Ana volunteered that she has frequent “hissy fits” when her mother says no to her demands. I continued my assessment sessions with more time with Ana and Blanche and Ana alone, and then a followed up with a parent-feedback session with Blanche.

The Diagnosis? Oppositional Defiant Disorder, According to our DSM Categories

My diagnosis: a child trying hard to Manage day to day, who lets loose her frustration when her mother, pressured and Managerial herself, breaks their connection while disciplining. Both are sad, tired, and longing for soothing. Ana’s tantrums are self-preservative—“You can’t control me!” (“I am my own person, and I will be in charge of how close and how far we are emotionally.”) The fight buffers an underlying sadness and loss. The Functional Hypothesis states that symptoms are coping mechanisms. When Ana and Blanche sit in my office, I see this clearly.

When a child is referred for psychotherapy, she has been labeled as a “problem.” Problem children come in two general clusters: externalizing symptoms, such as defiant behavior, being socially challenging or aggressive, addictions of alcohol and drugs, or internalizing symptoms, such as anxiety, obsessions, compulsions, depression, and somatic complaints. The tendency is to label and try to remove the symptoms. This is consistent with the Medical Model that is prevalent in our society. The Medical Model will bring in “experts” to “cure” the child—usually by means of medication, psychological testing, educational evaluations, special education, tutors, etc., all with good intentions, to help. Unless this is done in a very careful, humanistic context, the treatment offerings will alienate the child and have her believe that she is “damaged goods” and not accepted as is. This process of pathologizing the child can lead to a lifetime of marginalization. Rather than lead to a “cure,” this form of treatment can deepen the already perplexing problems faced by parents and educators. Even when symptoms abate, damage will have occurred via over-management and coercion of the youngster.

In contrast, the MetaModel is a depathologizing model. It assumes that symptoms are adaptational strategies for survival. When a child is defiant, he is expressing an attempt to cope with painful feelings and relational constraints. Parents are often feeling extremely agitated and powerless. They, too, are attempting to cope with painful feelings and relational constraints when viewed in context. In this book we will explore how the MetaModel places child symptoms in context to understand their functional nature, and how to generate treatment strategies that are accepting and depathologizing. With the MetaModel, the therapist will engage the child and family in a collaborative experiential process that links to the self-curative aspects that each human being possesses.

The MetaModel used in this book will be based on Internal Family Systems Therapy (IFS) as developed by Richard C. Schwartz, PhD. It is my belief that IFS is the most effective MetaModel in bringing out the clients’ strengths in a humanistic manner. The IFS approach is most consonant to human nature and is a comprehensive, deeply healing model. IFS will be introduced below and will serve as our vocabulary for the MetaModel of healing as well as the process of therapeutic intervention. The MetaModel is consistent with the Common Factors Model (Hubble, Duncan & Miller, 1999; Duncan, Miller, Wampold & Hubble, 2010), Contextual Model (Wampold, 2001), and Second-Order Change Model (Fraser & Solovey, 2007), models that have the most potent empirical support for emotional healing. Here we apply these principles to the treatment of troubled children and their families.

It will be useful to address the issue of evidence-based treatment from the outset. Evidence-based treatment is founded in testing scientific hypotheses via empirical findings scrutinized through the lens of double-blind randomized trials. This is known as the Medical Model. The complexity of this process for psychotherapy is explored and clarified by Wampold (2010). The field of psychotherapy has tried to align itself with the medical model in the hopes of legitimizing itself and establishing guidelines for applying specific approaches for particular disorders. When rigorous studies are performed, it turns out that “a variety of treatments, when administered by therapists who believe in the treatment and when accepted by the clients, are equally effective… there is little evidence that the specific ingredients of any treatment are responsible for the benefits of therapy” (Wampold, 2010, p. 71). The statistical differences that are discovered are due to the qualities of the therapist-patient relationship that can bring out the healing capacity of the clients. These qualities are called “Common Factors.”

Will Internal Family Systems Therapy just turn out to be another approach that is as good or as limited as all the others? My opinion is that IFS is on a meta-level, consistent with the Contextual Model Common Factors of the therapist-client alliance that is able to access client factors for emotional healing. It is a model that lifts constraints from natural healing processes of the client, akin to releasing the curative nature of the person’s autoimmune system, which staves off intrusive germs and is able to repair injuries that inevitably occur in life. In addition, there is a qualitative difference in the study of the psychological/emotional sphere of human nature and the study of isolated biological systems. Therapists are more like naturalists studying cultures and tribes than laboratory investigators (Bateson, 1972; Haley, 1981). The former, for success to occur, need to invite in every detail and dynamic, whether neat or messy, clear or confusing. On the other hand, laboratory scientist needs to “control” the experiment by ruling out any extraneous factors that may contaminate the matter being studied. It is important to note that the field of contextual theory that became the family systems therapy field was begun by Gregory Bateson, who was a naturalist and ethnologist, married to Margaret Mead, an anthropologist. Bateson and colleagues were the first to study families of schizophrenic patients by having two therapists in the room with the family and the rest of the team placed behind a one-way mirror to study the pattern of communications. This would be similar to the participant-observer model in naturalistic investigations. It is my contention, then, that therapists are immersed in “field studies” and our “data” is wide ranging. According to the Common Factors Model, the placebo effect, so crucial to “control” in the Medical Model, has actually turned out to be, in large part, the healing aspects in the psychotherapy contextual model, i.e., it is not the specific technique applied but the cultivation of a healing therapist-patient relationship that will bring forth the natural ability of the patient to repair psychological trauma.

The Internal Family Systems MetaModel is summarized below and woven throughout this book as a way to further understand and clarify how healing occurs, both as a road map for the therapist and as the operational vehicle for making the healing occur (Schwartz 1995, 2001; Schwartz & Goulding 1995).

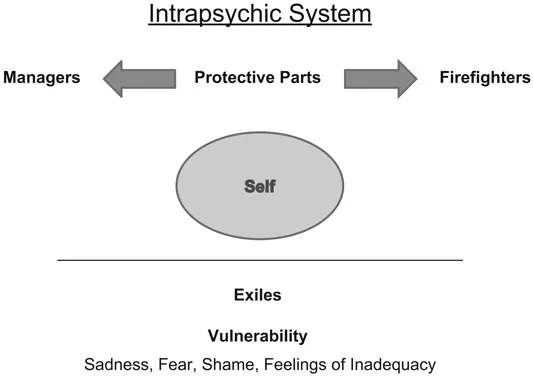

IFS is a model that elucidates the themes of family therapy and extends the work to the internal, intrapsychic world of the client. IFS views the internal psychological world of human beings as made up of an ecological system of Parts or subpersonalities. The choreography of the Parts is consistent with the models of family systems therapy as applied in the relational sphere. At the center of the internal system is the core Self that holds and expresses the compassion, courage, curiosity, clarity, confidence, creativity, calm, and ability to connect to others. According to the apocryphal story, an admirer asked Michelangelo how he was able to create the magnificent sculpture of David from a solid block of marble. Michelangelo replied, “David was in there all along, I just knew how to bring him forth.” In other words, the Self is that good, healing energy that the therapy process “brings forth” when it is successful. These attributes of Self are consistent with Eastern philosophy and teachings, and the focus on self-efficacy and self-acceptance are woven throughout the more recent conversation about Common Factors.

Here, Self is our basic pure human nature that we possess from birth. It is the pure “David” who lives in the block of marble, waiting for a gifted artist to bring out. For all of us to some degree, this healing energy of Self is blocked as a result of traumatic emotional experiences, imperfect caretaking, and existential anxiety (Becker, 1973). As a result, we carry sadness, fear, shame, and emotional pain that is not fully metabolized because we were too young and ill equipped to process it and because parents were not fully available and not fully capable in helping us through these experiences, due to their own constraints on Self-energy. The residue of this emotional pain is labeled Exiles in this model. For our survival, the full experience of Exiles is felt to be too overwhelming, so they are compartmentalized and guarded at all costs.

In order to help accomplish this banishment of emotional pain, two sets of other Parts are activated. One category is called the Managers. These Parts emphasize internal and interpersonal control and do all that they can to keep the “gate” locked so that the person does not go too close to the experience of painful Exiles. The Managers protect the Self from this pain (functional hypothesis/survival strategy) but in the process create new difficulties and limit the healthy range of being in Self, intrapsychically and relationally.

On the other end of the spectrum, is another set of protective Parts, called Firefighters. These Parts serve the same purpose as Managers, i.e., to protect the emotional pain from overwhelming the person. Firefighters act to soothe and distract from this pain (functional hypothesis/survival strategy). The most common Firefighters are addictions of all sorts, providing a “quick fix” analgesic to the long-held residue of trauma. As Managers and Firefighters are called into service of blocking intrapsychic pain, the energy and qualities of Self are eclipsed. As Self is constrained, defensive and self-protective survival strategies (i.e., Managers and Firefighters) play a dominant role in our internal emotional system and interpersonal relational experience, and who we are (our identity) begins to resemble these defensive parts and not our compassionate, competent Selves. So, consistent with our central theme, the solutions in the service of protection of our emotional system, when overworked, will create new constraints on our mental health.

The therapeutic process in IFS is to help guide the Self back to its rightful leadership position within the internal system through safe, experiential exploration. First, protective Managers and Firefighters need to be differentiated and unblended from Self. Recognition of the positive intentions of these Parts—their protection of the person—is a central part of this process and a direct application of the Functional Hypothesis. Once the Self-energy is liberated, the next phase of treatment consists of unburdening the Exiles so that there are new degrees of emotional freedom throughout the internal system.

The IFS Model places great emphasis on the process of unburdening the remnants of trauma held by the Exiled Parts. It is necessary but not sufficient to apply the Functional Hypothesis without having the Self of the client experiencing the emotional pain as the client and the therapist bear witness to this experience. Without this deep emotional process, the client will not be fully free from the effects of past trauma and will predictably become re-traumatized from intrapsychic and/or interpersonal triggers that are embedded in body memory (Pert, 1997; Rothschild, 2000; Ogden et al., 2006). This is consistent with an ecological (systems) model. As the Functional Hypothesis is applied so that the Self is in a leadership position, Protective Parts will become activated, vigilant in their attempts to buffer the surfacing of pain. Ultimately, this pain seeks expression and needs healing and unburdening. Clients often choose to create a ritual through which to unburden deeply held emotional pain. This is consistent with Garfield (1992), who views therapeutic rituals linked to reattribution as a meta-level process in all therapy models. Changes in the internal emotional system can powerfully affect changes in the external system (child’s family). Working on both levels will be crucial in this model, as will be demonstrated throughout this book.

In the chapters ahead, we will learn how to understand the world of children using the Internal Family Systems MetaModel and how to apply the essence of psychological healing.

Figure 1.1 Intrapsychic System

Glossary of Terms for the Internal Family Systems MetaModel

The following list of terms that articulate the Internal Family Systems MetaModel are offered to readers as an aid to familiarize themselves with the vocabulary of this book. You are invited to refer to this glossary as you embark on the further exploration of the model and its applications, and to revisit these terms as frequently as needed to strengthen the connection to and comfort with the model.

Beyond grasping these terms cognitively, clinicians are encouraged to use “Parts Language” with children and their families. This in itself is depathologizing and fosters a healing atmosphere centered on acceptance.

- Self The Self is our center, our essence, present from birth. It is who we are and is separate from roles that we play and agendas that we take on. The Self contains powerful qualities such as calmness, curiosity, clarity, compassion, confidence, creativity, courage, and the ability to connect to others. When the internal emotional system is in balance, the Self is in the leadership position, able to bring its qualities to us intrapsychically and interpersonally. These qualities can be experienced in the body and the client is guided to identify the state of Self in session and in their daily life.

- Exiles All of us have experienced trauma, from mild to severe, as the external world does not always provide for our safety and developmental needs. In extreme cases, such as abuse, events have been life threatening. Exiles, especially when experienced in our young and vulnerable years, can threaten to overwhelm our emotional system with sadness, fear, shame, and feelings of inadequacy. We as human beings possess the ability to isolate and prevent these extreme feelings from flooding through and overwhelming us. From their compartmentalized position, Exiles exert a powerful impact on our lives. The ultimate goal of psychotherapy is to gain access to Exiles and to lift the effects of the emotional trauma (burdens) that they carry.

- Protective Parts The intrapsychic system of our personality is organized to protect us and to help us adapt to our family and social environment. When traumatization has been severe, our Protective Parts work very hard to contain Exiles and the emotional burdens they carry. These Parts exist in two general clusters, Managers and Fire-fighters. While these Parts do buffer emotio...