![]()

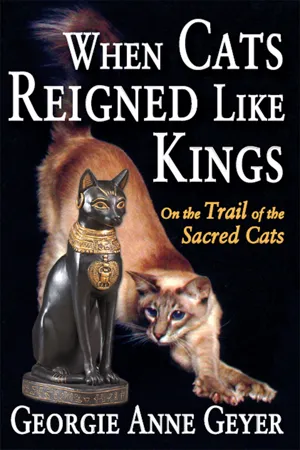

PART ONE

ON THE TRAIL

OF THE ROYAL

AND SACRED

CATS

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

AN EGYPTIAN GOD CAT,

LOST ON THE STREETS

OF CHICAGO

If the traveler can find

A virtuous and wise companion

Let him go with him joyfully

And overcome the dangers of the way.

BUDDHIST PROVERB FROM THE DHAMMAPADA,

THE SAYINGS OF THE BUDDHA

CHICAGO:

There was no reason to go out that hot, sticky July morning in 1975. There was no possible excuse for me to leave my mother’s apartment on Barry Avenue in Chicago at exactly 10:28 A.M. and walk to the corner to mail one letter. It was not even an important letter and could easily have waited until later. I was home with my mother between trips. As a foreign correspondent, I struggled to study, understand, and somehow encapsulate the complex human cultures of the world, and I was usually writing at that time.

There are many who will rightly insist that nothing was foreordained about such a fated meeting on a Chicago street corner. There are those who will also argue that it was crazy to dream of finding a royal cat, albeit one of recent and suspicious lineage and travels, masquerading as a Chicago street cat. They are right on one point: five or ten minutes either way, and I wouldn’t have seen the charming creature at all!

Indeed, when I came upon that lean, scrawny, Wizard of Oz scarecrow of a kitty lost on the streets of Chicago, with his long legs and his pinched little face and an odd black spot on the very end of his nose, I had never heard the names Bastet or Mau, much less Freyja or Maneki Neko. Oh, I had heard loosely of the sleek Siamese cat and her fluffy, pug-nosed Persian half sister, but I had never heard of all the other great breeds of the Family of Cat, such as the confounding Burmese, the mysterious Birman, the curious Chinchilla, the avidly swimming Turkish Van, or the slightly scary, black-as-night Bombay. I could never have guessed how impoverished I really was.

Before I found the kitty that summer’s day of 1975, displaced on the streets of Chicago by some still-unknown destiny, I had barely known that the cat was considered a god in ancient Egypt. I had no knowledge of those ancient biblical tales that contend that, during the long weeks when Noah’s Ark floated over the invading waters, rats and mice increased so alarmingly that Noah passed his hand three times over the head of the lioness, before she then sneezed forth the cat. Because of its success in eliminating vermin, it was also the cat that led the procession out of the ark when the rains finally stopped.

I was not aware that the Prophet Muhammad was so devoted to his pet cat Muezza that he once cut off the sleeve of his garment rather than disturb the little fellow who had fallen asleep there. Or that centuries later, in his African hospital, Albert Schweitzer began to write his prescriptions with his left hand because his beloved cat, Sizi, would fall asleep on the right arm of his shirt. I surely had never heard of Lao-Tsun Temple, although eventually there would come a time when I was sorry that I had heard of it!

I had yet to discover that the furry Birman cat had earned its pristine white paws centuries ago when it touched the bier of its king or that the Peruvian city of Cuzco is laid out in the form of the sacred puma. I still did not know that the charming, poetry-creating bushmen of southern Africa, who were so respectful of the supernatural qualities of lions that the very word for the beast—n!l, spoken with a clicking sound made by the tongue—was like the name of God and could not be uttered in daylight. Yet although I did not exactly know these things, I was hardly surprised to learn that writers (Petrarch, Charles Baudelaire, John Keats, Percy Bysshe Shelley, William Wordsworth, T. S. Eliot, to name only a few) loved cats, while most dictators (Hitler, Napoleon, and Stalin, among others) not surprisingly hated them: cats were simply too free and selfdetermining ever to prove agreeable to such human tyrants.

I did not know then, although I sensed it on different and mysterious levels, that after this fated meeting I would enter a new world, a world that is still with me and will be forever. It is a world in which I would be driven to explore, examine, and immensely enjoy history’s lessons in order to understand the relationship of cat to man.

It was most unusual to see a friendly young animal like this in our area of high-rises and busy streets. Thus, on that auspicious July day, I stopped in my tracks when I saw him—he was pacing efficiently in little measured steps, back and forth, along a brick ledge that edged the sidewalk—and we stared at each other for a long and searching moment. He had a most forthright gaze, charmingly clear, and as our eyes met I had the strangest feeling that I had known him for many, many years—even centuries.

Still, I only patted him on the head, and as I did so, the small creature purred like a veritable industrial machine at the height of production hour. Then he suddenly elongated his whole body in what I would come to call his “Halloween Cat” stretch, arching his back and thrusting his tail out in a daring, saucy greeting. His flexible little shoulders hunched up as if to attack, but he only purred some more. Then he meandered with the studied and casual nonchalance of a feline Fred Astaire over to some nearby bushes, and proceeded to sip some milk from a plastic container placed there, probably by the wanton person who had left him out all alone.

Before I could escape this encounter, with a flick of his tail he was back, staring at me fixedly, the yellow eyes as deep and impenetrable as amber pools. This kitty’s fur was revealing. He had a rich but flat white coat with black spots scattered artistically down his back, long white legs, and a dramatic black spot of fur right on the top of his head, which looked like a hairpiece parted exactly in the middle of his head. All I really knew was that he was assuredly one adorable young kitten, probably between four and six months old, with a black-as-midnight tail that flicked like lightning, twitched creatively, and managed to cover astonishingly large expanses in every direction. As I greeted him, he acknowledged my every word with a quirky swish of his luxuriant tail.

I had always loved animals, but in our modest bungalow on the South Side of Chicago, our family had only small “black-and-tan” dogs that came from a farm in Ohio. Cats were not exactly favored or pampered pets in those days. They were left outside to roam and range, and so they were almost always mangy, furtive, and unfriendly. My favorite books as I was growing up were Albert Payson Terhune’s volumes about his beautiful collies in New Jersey, all extraordinarily valiant creatures whose noble deeds would leave me recurrently and inconsolably in tears throughout my childhood.

“I hope that kitten is gone when I get back,” I said to myself halfheartedly that day as I crossed the street to the mailbox. After all, I was about to move to Washington, D.C., and at this point in my life a pet would only be a burden. My mother already had a cat—a scourge against humanity named Mookie—and hardly needed another such “pet,” given her wretched experience. Yet when I returned moments later, there he was, staring at me with such an ineffable calm that now I unhesitatingly scooped him up and swept him into the apartment, where he settled into my arms like some sweet child who had been lost and now was found.

In our first hours together, he adjusted to the apartment just as easily and comfortably as if he were thoroughly inured to the ways of the city. After introducing him to my big brother, Glen, and to our close friends, I began to wonder about an appropriate name—but that could wait until tomorrow. It had already been a full day.

The next morning, I found the kitten—my kitty now—sleeping next to me. It evoked in me the strangest feelings to see that he was curled up on his side in the same position in which I had been sleeping, his lanky cat limbs surreally askew exactly the way mine were. Already I sensed in our relationship a parallelness and a strange and even magical togetherness that would soon enough come to haunt me. When I got up, he barely stirred, but when he did, he stretched briefly, with a consciously restrained movement that seemed strange in such a small, young, lost animal. Then he examined me again with that penetrating gaze, his eyes staring fixedly into mine. At that moment he seemed to be an ancient and wise creature.

He also immediately began to invent and then display his games for me. For instance, that first morning the summer sun was gleaming and glittering in a kaleidoscope of light reflecting off Lake Michigan and playing all over the walls. How the kitten loved these flittering, flickering pools of light that were playing such wondrous tricks on him! First, a beam would appear, and he would naturally try to climb the offending wall. What else could any self-respecting cat be expected to do? Then several beams would sweep the ceiling, and the little puss would leap up and down, trying not to let a single beam escape. He reminded me at times of a philosopher searching in every dark corner for the light of truth. How he scampered around the apartment that morning, trying with all the charming abandon of youth to catch and capture the light!

I knew the intention: I had tried to do the same many times. He never quite did catch it, but then, how many of us do?

I had already been to Egypt several times in the late 1960s and 1970s in my work as a correspondent for the Chicago Daily News, and I had seen the Egyptian cats etched on the walls of tombs and on every sort of statue in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. For just a fleeting moment that first morning with my kitten, I thought those Egyptian cats reminded me a lot of this cat, with his long, lean, almost languorous body, his pinched and knowing face, and his regal, upright bearing. Could he perhaps be a feline from somewhere far, far away? Being quite enough of a romantic, I did not dismiss the possibility, but how could he have arrived at Barry Avenue on the North Side of Chicago?

I decided it might well be appropriate for him to have a Middle Eastern royal name. I tried Emir—no, the syllables were too harsh. I toyed with Sultan—again, not enough of those imprecisely warm sounds that cats like so much. Then I hit upon Pasha. The pashas were men of high military and civil rank in both Egypt and Turkey. More important, the shhhh sound absolutely engrossed the cat!

“Pasha,” I said aloud to him that first afternoon. “PASH-a!” His ears twitched with excitement as he came to attention, and his regal plume of a tail plop-plopped uncontrollably with all the unpretentious, natural spirit of a plebian cat who had suddenly come across a field of sparrows. “PASSHHA …” I repeated. At this, he rolled over onto his side, tipping his head toward me, his ears on the alert and his eyes gleaming. I had to admit that some of the historical, spiritual, or even cultural implications of the name were lost in his spontaneous response.

But they were not lost on me. The name had the correct political connotations. The Egyptians had abolished the office and even the term “pasha” in 1952, when they entered their modern nationalist and revolutionary period. Thus, I could not be accused of elitism but only of historical romanticism. Pasha it was—ever after.

Of course, being a responsible person, I did have some lingering concern that he might actually belong (if that word can be applied to any cat) to someone else. So I scoured the papers for a few days, and if I had found an ad in the “Lost” column saying, “Royal Egyptian cat from the Third Dynasty lost at Barry Avenue and Sheridan Road at 10:28 A.M. on July 28. Answers to the name ‘Pasha.’” I would surely have returned him.

So it was that a game centered around Pasha’s origins soon became a most serious search. All my life as a journalist and as a writer, I had been searching for truths about different cultures and how they related to one another. I had often remarked to people, “I became a journalist and explored the world in order to explain it to myself.” Now I had with me a mysterious, devoted creature whom I could not explain at all; much less describe our special relationship.

I began to wonder, “Who am I, and where did I come from?” and “Who is he and where did he come from?” Those questions would soon take me across the entire globe.

First, of course, I tried to “place” Pasha by his breed—if indeed he had one—through the nice veterinarians at our local McKillip Animal Hospital, where I took young Pasha for his shots and exams. He needed extra care, for he obviously was a cat with a “shady” past. Pasha would sit quietly in his carrier until he saw the vet. Then, some spirit of ancient shaman, some streak of banshee, some strain of hyena, perhaps, would suddenly overcome him, and he would begin to howl! I do not mean cry. The noise, which was truly terrible, would pause only at those moments when he needed to catch his breath, and then move on, sotto voce. All his life, this otherwise serene, composed creature hated vets with an unquenchable rage.

In between the bloodcurdling screams, I would always find time to implore the vet for information on my friend’s unknown past: “Do you think he might be Siamese? Oriental? After all, he doesn’t meow, he gurgles.”

The vet invariably looked at me pityingly and pronounced with a tight, unequivocal smile: “American Shorthair!”

At first this response hurt me to the quick. Then it came to me: I had before me a Chicago example of what happened all the time in Asia and other parts of the Third World. In many of those lands, they protected babies from kidnapping, from mortal danger, and from the resentment and jealousy of the gods by pretending that a beautiful newborn baby was hideously ugly. They would say of the child: “He’s an ugly little mud pie, isn’t he?” Or, “Too bad, she’ll never get a husband.”

After that, the vet’s words never hurt me again. Indeed, sometimes I would tickle Pasha on the head and ears and say fondly, “Hello, my little shorthair.” It was all in the true spirit of Catherine the Great, who, upon choosing a handsome colonel for her bed, would cajole him endearingly with, “Hello, my sweet serf.”

Another reason I knew that Pasha was unusual was that he was a mischievous and endlessly creative prankster. He designed tricks and then displayed them to me, sometimes with notable impatience if I did not take part immediately. He would jump over a box in the apartment, then come over to me and put his head in my lap, then jump over the box again, until he felt I was paying him sufficiently fond attention. Then he would tire, of course, and like all good cats, would need a little snooze for, say, sixteen or eighteen hours.

Indeed, Pasha was a classic rogue operator, an engaging trickster ever full of artful maneuvers. One day he suddenly came racing out of the bedroom toward an innocent visitor, terrifying her so much that she p...