Introduction

Reacting to the poisoning of the Russian double-agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia on British soil on March 4, 2018, the UK Prime Minister, Theresa May, called the incident, in her statement to the House of Commons, an “unlawful use of force” by the Russian state against the UK (Asthana et al. 2018). Two days later, the leaders of Great Britain, US, Germany and France released a joint statement strongly condemning the Salisbury nerve agent attack as “an assault on UK sovereignty” and saying it was highly likely Russia was behind it (Walker and Roth 2018). The Russian government tried to distance itself from the incident (Osborne and Carroll 2018), but its denials made little impression on the UK government and its allies. As the situation soon evolved into a full-scale information war (Barojan 2018), the public discussion turned to examining and understanding the potential strategic implications of the attack.

The act of engineering a confrontation with the UK a few days before the Russian presidential elections on March 18 could have generated a number of political benefits for the Russian President, Vladimir Putin, starting from boosting voter turnout and by extension, the legitimacy of the outcome in a campaign dominated by voter apathy. Furthermore, the attack could have served to drive a wedge between a Brexit-weary Britain and its allies or even to push the UK to retaliate against wealthy and prominent Russians in London, thus forcing them to seek closer relations with the regime back home (Harding and Roth 2018). In view of the track record of recent Russian interference in the domestic affairs of other countries for strategic gains, some of these explanations could sound reasonably plausible (Hille, Foy, and Seddon 2018), but short of a credible conceptual framework to validate them, these claims largely remain in the realm of informed speculation. With that in mind, would it be possible to reduce the degree of overdetermination of the effects of Russian actions by better understanding the patterns by which such actions are designed and implemented? In other words, is there a way by which we can make sense of whether a state can be strategically influenced to pursue a predetermined course of action in international affairs, especially against its own interests?

Enter the theory of reflexive control (RC), which, as discussed further below, represents one of the long-standing and influential doctrine of information warfare employed by the Russian intelligence services. In basic terms, RC can be defined “as a means of conveying to a partner or an opponent specially prepared information to incline him to voluntarily make the predetermined decision desired by the initiator of the action” (Thomas 2004, 237). Unlike the case of physical coercion (“sticks”) or economic inducement (“carrots”), RC seeks to exert influence by infiltrating the decision-making process of the opponent, who is thus covertly encouraged to pursue a course of action that favours the strategic goals of the initiator. In foreign policy terms, this is very powerful, as it could make the difference between war and peace or perhaps less dramatically, between diplomatic success and failure. Basically, RC allows one party to “hack” the diplomatic game so that it can shape the preferences of the other actors towards a desired outcome.

The RC strategy can hardly be faulted for lacking ambition, but it creates a level of expectation that might be hard to deliver in practice. After all, the ambition of influencing “collective attitudes by the manipulation of significant symbols” or simply put, by propaganda (Lasswell 1927, 627), has informed the thinking of political leaders, military strategists and diplomats for centuries with very mixed results, to put it mildly. RC could suffer the same disappointment, largely because people learn quickly how to resist efforts that seek to control them against their will. In addition, the concept of RC rests on a set of Hobbesian assumptions about the international system that are likely to induce international actors to see each other in very dark colours, so that even positive forms of diplomatic engagement could be interpreted as signs of deception and strategic manipulation.

This is why it is important to carefully unpack the conceptual underpinnings of RC: so that we can acquire a better understanding of how RC works; what limitations it faces; to what extent its claims can be validated empirically; and, equally importantly, to what extent RC can be “reverse-engineered” so that effective means of protection against it can be designed. What probably lends extra credibility to RC today is the arrival and spread of digital platforms, and the opportunity they create for RC proponents to use social media data to build detailed cognitive profiles on the basis of which RC controllers could imitate the reasoning process of the target audience and then to use this information for micro-targeting specific audiences. This chapter starts by providing a brief background to the concept of RC, discussing its mechanism and mode of operation; continues by reviewing the analytical contributions and limitations of the concept to understanding patterns of disinformation, especially in a digital context; and concludes by suggesting a four-layered funnel of digital RC by which the scope, reach and effectiveness of the strategy could be assessed and influenced.

The theory of reflexive control

In a study commissioned by the US Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California, towards the end of the Cold War (Chotikul 1986), the scientific development of the theory of RC was traced back to the early 1960s and the work of Dr Vladimir A. Lefebvre, a military researcher in the former Soviet Union, who later emigrated to the US. As Lefebvre indicated in one of his first books on the topic,

In short, by understanding the thinking process of a particular individual, one should be able to steer him/her to taking actions in a desired direction. The key question is, of course, how to do this?

RC theory, as Lefebvre and his team conceptualised it, has a dual aspect that considers both the process and the outcome of the disinformation strategy. On the process side, RC can be conducted through the transformation of the opponent’s information processing (the cognitive dimension) or through the careful selection of messages presented to the person subjected to RC (the informational dimension). For example, a tourist could be induced to travel to city X if appealing information about the destination is made available to him/her or if his cognitive mechanism of evaluating touristic destinations is altered to include criteria that favour attractions in city X. On the outcome side, RC can facilitate a “constructive” result, in which the opponent is influenced to voluntarily make a decision favourable to the controlling side, or a “destructive” result, in which means are employed to destroy, paralyse or neutralise the procedures and algorithms of the enemy’s decision-making processes (Lefebvre and Lefebvre 1984, 144–145) (see Table 1.1). Using again our earlier example, the tourist could be “constructively” induced to travel to city X or “destructively” prevented from travelling to the competition, city Y, either by offering him/her negative information about city Y or by heightening the appeal of those criteria in his mechanism of assessing tourist destinations that do not favour the type of attractions offered by city Y.

Informational control for either “constructive or destructive” purposes is the most common form of propaganda, and it has been used for centuries in various manifestations. Diplomacy in Byzantium was characterised, for instance, by an elaborate propaganda system intended to impress “barbarians” of the political and military superiority of the empire, its longevity, grandeur and the contrasting fates of its enemies (Hamilton and Langhorne 1995, 16). The strategic objective of the entire court ceremonial was to discourage vassals and rivals from challenging the authority of the emperor by controlling the informational context based on which visitors could assess the political or military situation of the empire. The idea introduced by the theory of RC of altering or corrupting the decision-making process of the opponent goes a step further by seeking to control not only what B perceives (e.g., the dazzling symbols of power of the imperial office) but also how he/she takes decisions on matters relevant to A (e.g., whether it attaches the same weights and benchmarks to assessing the geopolitical situation as the emperor). The RC theoretical ambition is clearly high, but does it work in practice? Lefebvre’s suggestion that “in contrast to a scholarly debate, the most inventive liar wins in conflict” (Lefebvre and Smolyan 1968 (1971), 18) does little to alleviate doubts and leaves the question open to interpretation.

TABLE 1.1 Processes and Outcomes of Reflexive Control

| Constructive | Destructive |

Cognitive | B is induced by A to alter his/her decision-making algorithm to facilitate outcomes beneficial to A | B is induced by A to revise his/her decision-making algorithm to avoid outcomes detrimental to A |

Informational | B is induced by A to assess the situation in a manner that facilitates outcomes beneficial to A | B is prevented by A to assess the situation in a manner that may lead to outcomes detrimental to A |

In a more recent overview of the theoretical developments in the field of RC, Timothy Thomas, a former director of Soviet Studies at the US Army Russian Institute, traced the evolution of the theory since 1960s and found that the concept did not fade with the collapse of the Soviet Union, but it actually remained high on the research agenda of the Russian military and intelligence community at the end of the Cold War. Furthermore,

Thomas’s observation is important because it demonstrates continuity in strategic thinking between the military and political elites of the Soviet Union and those of post-Cold War Russia.

Some of the RC tactics recommended by the new generation of Russian military analysts sound, for instance, eerily similar to the type of disinformation operations that the European and American public has faced in the recent years: offering information that discredits the government in the eyes of its population, frequently sending the enemy a large amount of conflicting information, convincing the enemy that he must operate in opposition to coalition interests (Thomas 2004, 248). In a separate article, focussed on the Russian intervention in Ukraine in 2014, Thomas examines the extent to which RC measures have moved from theory to practice. The use of false analogies (Crimea vs Kosovo), military provocations (unannounced flights over the Baltic countries) or blame projection (accusing the West of targeting Putin with an information war) are, for instance, some of the RC measures deployed by Russian authorities, prior and during the annexation of Crimea, as a way to control the informational context, shape favourable perceptions about Russia during the crisis and prevent Western countries from taking actions detrimental to Russia (Thomas 2015, 456–458).

While the first generation of RC studies largely focussed on conceptual development (what RC means as a process and outcome), current investigations conducted by Russian military researchers seek to understand how the concept works in practice from a tactical and strategic perspective. At the tactical level, the issue of concern is the “reflex” component of the theory, that is, the process of unpacking and imitating the mode of reasoning of the opponent. Gaining access to the cognitive “filter” of the opponent (knowledge, ideas, experience) would presumably help one understand and copy how the opponent makes sense of the situation he or she faces and how he or she takes decisions. Close knowledge of the opponent’s “filter” (habits, socio-psychological profile, preferred modes of social interactions, etc.) is therefore critical for maximising the chances of success of RC, but this is a challenging task as such volume of information is not easy to collect or interpret and to render it into actionable recommendations.

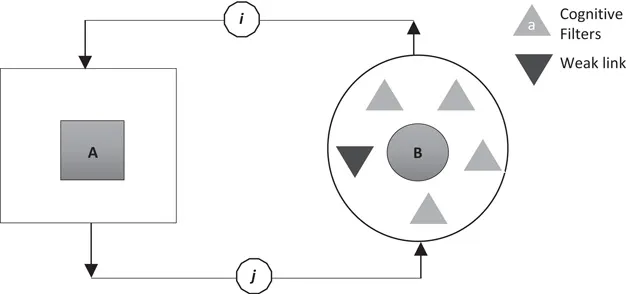

The alternative to developing detailed maps of the cognitive “filter” is to locate its “weakest links”, that is, those intellectual, moral or personal characteristics on which the opponent relies the most for making judgements about matters of interest to him (see Figure 1.1). For example, if one is prejudiced, then feeding the source of his prejudice becomes the “weak link” to be exploited against him. Alternatively, if one is prone to narcissism, then boosting his ego with flattery and compliments could make him react more positively to your ideas. Drawing on writings of Russian military strategists, Thomas calls the process of locating the “weakest link” the “chief task of reflexive control”, and rightly so as the side with the highest degree of reflex (i.e., with the best capacity to imitate the opponent thoughts or predict its behaviour) has the best chances of winning the influence “game” (Thomas 2004, 241–242).

FIGURE 1.1 Tactical Model of Reflexive Control: A uses information i about B’s cognitive filters and “weak links” to induce B via information j to take decisions in line with A’s goals.

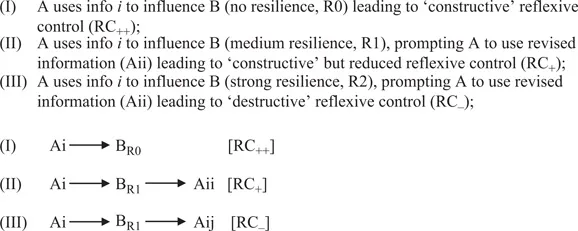

From a strategic perspective, the issue of concern is how the opponent reacts and adapts to RC. As one of the leading RC theorists, Colonel S. Leonenko, points out, RC is an interactive process, in which parties seek to influence each other to different degrees. For example, if side A acts independently of the behaviour of side B, then his degree of reflex relative to side B is equal to zero (0). If, on the other hand, side A makes assumptions about side B’s behaviour based on the thesis that side B is not taking side A’s behaviour into account, then side A’s degree of reflex is one (1). If side B also has a first-degree reflex (takes A’s behaviour into account), and side A takes this fact into account, then side A’s reflex is two (2), and so on (Leonenko cited in Thomas 2004, 242). A higher degree of RC demonstrates strategic sophistication, but it also makes more difficult for the parties to stay in control of the strategic game.

As Lefebvre and his team note in a recent article, methods of RC work best under the condition that the party that is being controlled does not know about this fact (see Figure 1.2). Otherwise, RC can damage the controlling party, since after discovering the influencing attempt, the controlled party may be able to reconstruct the intentions of the opponent (Kramer et al. 2003, 99–100). In other words, once resilience against RC is developed, the controlling Party A may compromise its ability to “constructively” induce B to take decisions in line with A’s strategic goals, but it may still retain the capacity to prevent B from taking decisions against A by “destructively” influencing his decision-making process through power pressure, deception or artificial time constraints (Ionov 1995).

To sum up, the theory of RC offers good analytical insight for understanding the conditions under which propaganda campaigns may work and why. By gaining access to the cognitive filter by which an opponent makes sense of the world, the controlling party might be able to induce him/her to voluntarily take decisions in favour or at least not against its interests. At the same time, the model comes with some important limitations. First, the theory carries reasonable analytical currency at the individual level, but its applicability arguably narrows at the group or society level. It is not very clear, for instance, how “cognitive filters” could be mapped for large groups and with what degree of efficiency. Second, the model works well when the controlled party is unaware of RC efforts against itself, but once the parties develop resilience against such strategies, it becomes increasingly difficult to measure the impact of RC.

FIGURE 1.2 Strategic Model of Reflexive Control.