![]()

1

Introduction

1.0 Chapter summary

Evidence from glacier ice, or left by glaciers in the landscape or within the geological record, provides one of the most important sources of information on environmental change. The Earth is a dynamic and constantly changing system, in which all components interact. Research on global environmental change aims to understand how these complex systems interact, and to identify linkages between them. This research may provide the basis for predicting future global environmental changes and their human consequences. Glacier monitoring using satellites, based on 20 years of space-based observations of glaciers, has been developed to build a database covering most glaciers of the world and to monitor changes in glaciers on a periodic basis.

1.1 The significance of environmental change

The Earth is a dynamic, non-static and constantly changing system, in which all components (the atmosphere, geosphere, cryosphere, hydrosphere, and biosphere including mankind) interact. Research on global environmental change tries to understand how these complex systems interact, and to identify the nature of linkages between them. This research may ultimately provide the basis for predicting future global environmental changes and their human consequences. To be able to forecast future environmental changes, an understanding of past environmental changes is essential. Such research concentrates on the time evolution of processes operating on time scales from decades to millennia and their interactions through time. Hopefully this will enable assessments of causes and effects in this complicated dynamic system. Palaeoenvironmental studies also show how rapidly Earth systems may respond to forcing factors, which is important in planning future environmental change. This research provides a database of environmental conditions in the past which can be used for testing numerical models of atmospheric, terrestrial and marine processes.

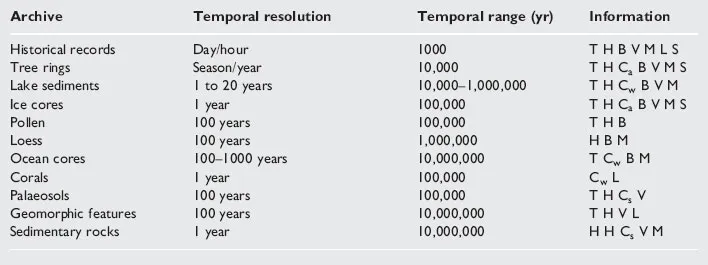

For the time prior to instrumental records, evidence of environmental change comes from ‘natural archives’ or proxy records (Table 1.1), providing information about palaeoenvironmental conditions including past atmospheric composition, tropospheric aerosol loads, explosive volcanic eruptions, air and sea temperatures, wind and precipitation patterns, ocean chemistry and productivity, sea-level changes, ice-sheet dimensions, and variations in solar activity. Of crucial importance, however, is the ability to date the different records accurately in order to determine whether events occurred simultaneously, or whether events led or lagged behind others.

Glaciers and ice sheets are some of the best archives of past environmental change, as demonstrated by ice cores obtained from the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets (see Chapter 3) and through the history of glacier fluctuations obtained from the glaciated regions of the world (see Chapter 5). Records of glacier fluctuations contribute important information about the range of natural variability and rates of change with respect to energy fluxes at the Earth’s surface over long time-scales. Reconstructed Holocene and historical glacier fluctuations indicate that the glacier extent in many mountain ranges has varied considerably during recent millennia and centuries, exemplified by the Little Ice Age and late-twentieth century weather extremes. The general shrinkage of Alpine glaciers during the twentieth century is a major reflection of rapid change in the energy balance at the Earth’s surface. An annual loss of a few decimetres of glacier ice depth is largely consistent with the estimated anthropogenic greenhouse forcing (a few W/m2). The rapid glacier retreat in the first half of the twentieth century was probably little affected by emissions of greenhouse gases. The later general retreat may, however, include an increasing component of human influence. Recent glacier shrinkage may now coincide with increased human-induced radiative forcing. Glacier mass balance measurements therefore become one of the key indicators for evaluating possible future trends.

TABLE 1.1 Characteristics of natural archives (adapted from Bradley and Eddy, 1991)

T: temperature; H: humidity or precipitation; C: chemical composition of air (Ca), water (Cw), or soil (Cs); B: biomass and vegetation patterns; V: volcanic eruptions; M: geomagnetic field variations; L: sea-level; S: solar activity.

1.2 Glaciers as monitors of environmental change

Glaciers and ice sheets are commonly located in remote areas far from population centres. Despite this physical and mental distance, past and modern glacial environments provide an important key to our knowledge of past, present and future global environmental conditions. Glacial environments may at first look chaotic and complex. However, few other environments exhibit such rapid, dynamic and spatially variable changes of processes. Past and present glaciers and ice sheets have had a significant impact upon all aspects of Earth systems. Understanding of many aspects of glaciers and glacier processes still remains poor. As an example, the complex relationship between ice dynamics and mass balance fluctuations is not fully understood. Modelling of ice masses and mass balance studies have, and will, advance our understanding of global ice-sheet fluctuations in the past.

The effect of modern glaciers on a global scale can be looked upon at two levels. Firstly, they impact upon humans and habitats in their nearby surroundings. Meltwater outbursts and rapid ice advances resulting in the loss of pasture lands, property and human fatalities are well documented (e.g. Grove, 1988). Secondly, there is the large-scale impact on the global climate and sea-level. Related to this topic is the controversial question of ice-sheet stability and whether the large ice sheets are melting at an increased rate, injecting large volumes of cold fresh water into the polar oceans, and affecting oceans and near-shore habitats, currents, surface ocean water temperatures and global weather phenomena.

Over the past several decades the techniques of studying glaciers have greatly improved. For example, satellite images have improved the accuracy of measuring ice movement and mass balance. Ice cores retrieved from the Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets have greatly improved our knowledge of past environmental changes. Computer-generated ice-sheet models have increased our understanding of ice-sheet growth and potential stability/instability as a result of predictions of future ice-sheet variations. In addition, there is growing knowledge of the likely spatial and temporal development of the Pre-Pleistocene and Pleistocene ice sheets, and the causative mechanisms that may lead to global glaciation, carbon dioxide variations, and biomass and productivity changes.

International monitoring of glacier variations began in 1894. At present, the World Glacier Monitoring Service (WGMS) of the International Commission on Snow and Ice (ICSI/IAHS) collects standardized glacier information, as a contribution to the Global Environment Monitoring System (GEMS) of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and to the International Hydrological Programme (IHP) of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The database includes observations on changes in length and, since 1945, mass balance. Most of the data come from the Alps and Scandinavia.

Two main categories of data – summary information and extensive information – are reported in the glacier mass balance bulletins published by IAHS. Summary information on specific balance, cumulative specific balance, accumulation area ratio (AAR) and equilibrium line altitude (ELA) is given for ca. or approximately 60 glaciers. This information provides a regional overview. In addition, extensive information such as balance maps, balance/altitude diagrams, relationships between accumulation area ratios, equilibrium line altitudes and balance, as well as a short explanatory text with a photograph, are presented for 11 selected glaciers with long and continuous glaciological measurements from different parts of the world. The long time series are based on high-density networks of stakes and firn pits. These data, most of which are now available on Internet, are useful for analysing processes of mass and energy exchange at the glacier–atmosphere interface and for interpreting climate/glacier relationships.

Glacier monitoring using satellites, based on 20 years of observations of glaciers by LANDSAT, SPOT, ERS and, in the future, EOS and Radarsat, has been developed to build a database covering most glaciers of the world and to monitor glacier changes on a periodic basis. Satellite monitoring of the world’s glaciers should produce a uniform image data-set, monitor special events such as glacier surges, produce maps of the areal extent of glaciers and snow fields, give information about glacier surface velocities, advance and retreat, and an inventory of the glaciers, including mean surface speed, length, width, areal extent, snowline, and the temporal changes in these parameters. Adam et al. (1997) evaluated the effectiveness of ERS-1 synthetic aperture radar (SAR) imagery for mapping movement of the transient snowline in a temperate glacier basin during the ablation season. Despite localized confusion between glacier ice and wet snow, the wet snowline can be mapped reasonably well by using ERS-1 SAR imagery.

Studies show that most Arctic glaciers have experienced negative net surface mass balance over the last few decades (e.g. Dowdeswell et al., 1997; Pohjola and Rogers, 1997a,b). There is, however, no uniform recent trend in mass balance in the Arctic, although some regional trends are recognizable. In northern Alaska, for example, glaciers experience increased negative mass balance as a result of higher summer temperatures. This development may be a response to a step-like warming of the Arctic in the early twentieth century since the end of the Little Ice Age. Maritime Scandinavian and Icelandic glaciers, on the other hand, show increasingly positive mass balance due to increased precipitation during the accumulation season (Pohjola and Rogers, 1997a).

Box 1.1 The concept of ice ages – historical background

Environmental change is a continuous process where dynamic systems of energy and material operate on a global scale to cause gradual and sometimes catastrophic changes in the atmosphere, hydrosphere, lithosphere and biosphere. During most of the Earth’s history the agents in the environmental system have been the natural elements (wind, ice, water, plants and animals). Some 2–3 million years ago, however, a new and perhaps the most powerful generator of environmental change, the hominids, emerged. The earliest testament to this are the cave paintings in many parts of the world. The first written accounts came with the rise of the ancient Mediterranean civilizations in Greece and Rome. Ideas changed little during the Middle Ages, when European scholars returned to the concept of a flat Earth. The bipartite nature of geography, first intimated in Strabo’s work, involved human and physical divisions. This concept was formalized by Varenius (AD 1622–1650) who originated the ideas of regional or ‘special’ geography and systematic or ‘general’ geography. The deductive and mechanistic philosophy earlier advocated by Newton (1642–1727) was continued in the work of Charles Darwin (1808–1882). In his classic work The Origin of Species (1859) he advanced theories of evolution and suggested a relationship between environment and organisms. By the end of the nineteenth century, the theory of the biblical flood as a major agent in shaping the face of the Earth was questioned.

The earliest descriptions of glaciers are in Icelandic literature and date from the eleventh century. During the Little Ice Age, glaciers around the world expanded considerably. In the Alps and in Norway the glacier advance led to destruction of pastures and property. The ice-age theory was developed during the nineteenth century. The main spokesman for the theory of ice ages in the early nineteenth century was Louis Agassiz, the influential president of the Swiss Society of Natural Sciences, who has been regarded as the ‘Father of Ice Ages’. Agassiz was, however, not the first to believe that glaciers had previously been more extensive, and he himself was sceptical for several years. Perhaps the first to document the evidence for more extensive glaciers was the Swiss minister Kuhn. In 1787 he interpreted erratic boulders below the glaciers near Grindelwald as evidence for a more extensive glaciation. Scot Hutton, one of the leading contemporary geologists, published in 1795 his ‘Theory of the Earth’ in which he described how ice had transported great boulders of granite into the Jura Mountains. A Swiss mountaineer and hunter named Perraudin argued in 1815 that glaciers had flowed into the Val de Bagnes in the Alps, and tried to convince Carpentier, who later became an advocate of the glacial theory, of his views. Perraudin also tried to persuade the Swiss engineer Venetz three years later, but he too was sceptical of the theory. However, Venetz began to accept the hypothesis and in 1829 he argued from the distribution of moraines and erratics that glaciers had covered the Swiss plain, the Jura and other regions of Europe. In 1824 the Norwegian geologist Esmark had already argued that glaciers in Norway had been much more extensive than at present. It was, however, the German poet Goethe who promoted the idea of an ice age (Eiszeit) in the novel Wilhelm Meister (1823).

Meanwhile, Carpentier accepted Venetz’s theory of more extensive ice, and started to collect evidence in favour of this hypothesis. At that time it was believed that the biblical flood explained the distribution of the erratics, and resistance was therefore strong to the ice age concept. In 1833 several researchers had accepted the view of Lyell, the leading British geologist of the day, that boulders had been deposited by icebergs, a theory (the ‘drift’ theory) developed in 1804 by the German mathematician Wrede. Darwin supported Lyell, and in a series of papers he advocated the theory until his death in 1882.

During a field trip to Bex, Agassiz was convinced by Carpentier of the truth of the glacial theory, which for the first time had a strong, forceful and influential spokesman. By now Agassiz and Carpentier were familiar with Goethe’s great ice age theory, but researchers ignored it because of his lack of scientific style. Unfortunately, Agassiz developed the glacial theory beyond available evidence, and when he presented the theory to the Swiss Society of Natural Sciences at Neuchâtel in 1837, he was met with great opposition. Agassiz published his work in 1840 in the book Etudes sur les Glaciers. The ice age theory substituted the Great Flood, of which Buckland, a professor of mineralogy and geology at Oxford University, was a great spokesperson. Buckland joined Agassiz on a trip to the Alps, but Buckland was still not convinced. After Buckland had discussed glacial deposits in Scotland and northern England with Agassiz, Buckland finally became convinced about the glacial theory. Agassiz moved to the US in 1847 as professor at Harvard University. Many researchers had already accepted his theory, but his appointment speeded up its acceptance, and when Agassiz died in 1873, only a few scientists had not yet accepted the ice age theory. Subsequently, tillites were found as evidence of ancient glaciations. Around the turn of the century, evidence for four ice ages were found in North America, the European Alps, Scandinavia, Britain and New Zealand. The first deep-sea sediment cores, covering most of the Quaternary, were obtained in the 1950s. Oxygen isotope studies of planktonic and benthic foraminifera were used to estimate palaeotemperatures and ice volumes. In the early 1970s it was assumed that the period of glaciations was equivalent to the Quaternary period (ca. 2.5 million years). In 1972, long cores retrieved from the Antarctic continental shelf in the Ross Sea showed evidence of glaciations 25 million years ago. Cores obtained in 1986 showed evidence of glaciations as far back as 36 million years ago (Oligocene). The precise timing of the onset of Cenozoic glaciation in Antarctica remains to be determined.

As evidence of environmental change accumulated, attention also focused on the underlying cause of climate change. The French mathematician Adhémar was the first to involve astronomical theories in studies of the ice ages. In 1842 he proposed that orbital changes may have been responsible for climatic change of such magnitude. The Scottish geologist James Croll advanced a similar approach in 1864, suggesting that changes in the Earth’s orbital eccentricity might cause ice ages. In the book Climate and Time he explained the theory in full. Due to the inability to date and test Croll’s hypothesis, his theory was not seriously considered until Milutin Milankovitch, a Serbian astronomer, revived the theory during 1920–40. The Milankovitch theory, or the astronomical theory of ice ages, has become widely accepted since the 1950s with evidence from the deep-sea records. The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries witnessed the establishment of new methods, mainly based on biological remains, thus establishing the field of palaeoecology.

A degree-day glacier mass-balance model was applied b...