- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Knowledge As Design

About this book

First published in 1986. We all play the roles of teacher or learner many times in life, in school and home, on the job and even at play. How can we strengthen those roles, striving for deep understanding and sound thinking? Knowledge As Design demonstrates the strong but neglected unity between learning and critical and creative thinking. Author David Perkins discloses how the concept of design opens a doorway into a deeper exploration of any topic, academic or every day. Knowledge As Design challenges the concept of knowledge as information. Drawing from current philosophy and cognitive science, the book shows how learners can attain a new level of insight when learning highlights the constructed and constructive character of knowledge. Any individual involved in formal or informal learning or teaching can benefit from the general outlook and specific principles laid out in this book. It offers a uniquely intelligent philosophy and psychology of understanding and critical and creative thinking.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

History & Theory in Psychology1

Knowledge as Design

The classic British science fiction author H. G. Wells once wrote a story about a man who wishes the world would stop turning. Troubled and in need of time, the hero of his tale wants tomorrow to come a little later. The conceit of Wells’ narrative is that the fellow gets his wish, but from that moment on all consequences follow according to natural law. The Earth stops turning, but the atmosphere does not. Enormous winds sweep down forests and farms. The oceans also keep in motion, heaving up onto the land, demolishing homes and factories. Bridges and skyscrapers, not part of the Earth, retain momentum, toppling over of their own impetus.

This whimsey about the price of idle wishes invites a like parable about human invention. Suppose that, tired of TV commercials and trendy boutiques, someone wishes that there is no such thing as design. After all, for most of us, design is a rather special word — the enterprise of admen, architects, and fashion czars. But broadly construed, design refers to the human endeavor of shaping objects to purposes. Let us, like Wells, follow rigorously the consequences of this wish. The clothes vanish from our bodies, never having been invented. The floors and pavements on which we walk slip away into nothingness. We find no books, no artificial lighting, not even a primitive hearth. We wander around the wilderness, mouthing at one another. And perhaps, if language itself can be considered a design, we do not even understand what the mouthings mean.

What is Design?

This parable dramatizes how pervasive and important design is: Our sophisticated lives depend utterly upon it. If building up and passing along knowledge is one characteristic of the human way, another is embodying knowledge in the form of a tool to get something done. A knife is a tool for cutting, a bed a tool for sleeping, a house a tool for sheltering, and so on.

In general, one might say that a design is a structure adapted to a purpose. Sometimes a single person conceives that structure and its purpose —Benjamin Franklin as the inventor of the lightning rod. Sometimes a structure gets shaped to a purpose gradually over time, through the ingenuity of many individuals — the ballpoint pen as a remote descendant of the quill pen. Sometimes a structure gets adapted by a relatively blind process of social evolution, as with customs and languages that reflect human psychological and cultural needs. But notice that in this book we do not use another sense of design: regular pattern that serves no particular purpose, as in ripples on sand dunes.

If knowledge and design both are so central to the human condition, then a speculation looks tempting. The two themes might be fused, viewing knowledge itself as design. For instance, you could think of the theory of relativity as a sort of screwdriver. Both are human constructs. Both were devised to serve purposes —the screwdriver physically taking apart and putting together certain sorts of things, the theory of relativity conceptually taking apart and putting together certain sorts of phenomena. That seems promising; at least “knowledge as design” poses a provocative metaphor. Indeed, perhaps knowledge is not just like design but is design in a quite straightforward and practical sense.

Knowledge as Information versus Knowledge as Design

What is knowledge? Fuzzy as it is, the question has some importance. How we think of knowledge could influence considerably how we go about teaching and learning. A stolid formula tends to shape how we see knowledge and the giving and getting of it: knowledge as information. The theme of knowledge as design can break the familiar frame of reference, opening up neglected opportunities for understanding and critical and creative thinking.

Through learning at home, at work, and in schools, we accumulate a data base of information that we can then apply in various circumstances. For instance, you know a friend’s phone number, the layout of your town or city, the rules of chess, your favorite foods, when Columbus discovered America, the Pythagorean theorem, the capital of Russia, Newton’s laws. You have this information at your disposal and may call upon it for whatever you want to do with it.

But can we consider knowledge in a different light, as design rather than information? That would mean viewing pieces of knowledge as structures adapted to a purpose, just as a screwdriver or a sieve are structures adapted to a purpose. You know your friend’s phone number —so you can call when you need to. Moreover, your knowledge is well-adapted to the purpose; the number is only seven digits long and well-rehearsed, so you can remember it readily. You know the layout of your town or city—so you can get to work, to your home, to the airport, wherever you want to go. Again, your knowledge is well-adapted; if you have lived in a place a while, you probably have a rather comprehensive “mental map” of the area that you can apply not only in finding places you normally go to but in navigating to new locations in the same area. Similar points can be made about knowing the rules of chess or your favorite foods.

For these examples of everyday practical knowledge, knowledge as design does make sense, but how about more academic knowledge? When you ask yourself what the purpose of a piece of knowledge like “Columbus discovered America in 1492” or the Pythagorean theorem is, you may not have a ready answer. Treating that sort of knowledge as a design —as a structure adapted to one or more purposes — does not come so easily.

The question is how to interpret the shortfall. Possibly knowledge as information is the right way to think about academic knowledge. On the other hand, perhaps academic knowledge can be thought of as design, but the “information attitude” toward knowledge that pervades teaching and learning in academic settings has let to our accumulating knowledge stripped of its design characteristics. In academic settings, we often treat knowledge as data devoid of purpose, rather than as design laden with purpose. To recall a theme from the introduction, much of the academic knowledge we hold shows a symptom of truth mongering—knowledge disconnected from the contexts of application and justification that make it meaningful.

If all this is so, by pushing the point one should be able to see academic knowledge as design after all. Indeed, sometimes the case that academic information has —or should have —a design character is easy to make. The theory of relativity was already mentioned. Consider its ancestor, Newton’s laws. These have a fairly transparent purpose: organizing a diverse set of observations in order to explain phenomena of motion, anything from the trajectory of a baseball to the orbits of the planets. Also, the laws have a parsimonious and powerful mathematical structure well-adapted to this purpose.

“Important facts” such as when Columbus discovered America pose a more difficult challenge. One might question whether the facts have that much importance after all. However, connected to significant purposes they at least take on somewhat more meaning. For instance, milestone dates like 1492 are pegs for parallel historical events. What was happening in Europe at about that time, or in the far East? For another, 1492 and other milestone dates in American history provide a kind of scaffolding for placing intermediate events. What happened in America between 1492 and the next milestone date? In such roles, a date functions not just as information but as implement, in particular a tool for grasping and holding information. What was mere data becomes design.

There is a tempting analogy here with Stanley Kubrick’s 2001. What is an old bone—just an object in the environment, or a tool? Surely Kubrick’s simians knew about bones long before the monolith, but not bones as clubs. Bones were simply objects lying around. But with the help of the monolith, the simians saw how a bone could be used as a weapon. Something like this applies to academic information also. To be sure, we have a fair amount of mere information sitting in our mind’s attic that does little more than wait and weather there, like old bones. But when a piece of data gets connected to purposes, it becomes design-like. In this way, all information potentially is design. Of course, not very datum we have functions as design or even can do so readily. All of us keep in storage a great deal of passive information, one might even say dead information. But that is part of the problem. There is little point in teaching and learning that provides primarily dead information.

In summary, knowledge as design makes sense. One can see both practical and academic knowledge through that lens. In various contexts and for various reasons, you might prefer one construal or the other for knowledge — information or design. In the context of teaching and learning, knowledge as design has much to offer. Knowledge as information purveys a passive view of knowledge, one that highlights knowledge in storage rather than knowledge as an implement of action. Knowledge as design might be our best bet for a first principle in building a theory of knowledge for teaching and learning.

Four Design Questions

All this is okay as far as it goes, but a mere attitude will not carry us very far unless we can elaborate it into a method. “All right,” a cautious voice complains. “You want to call the concept of ecology, Boyle’s law, and the Bill of Rights designs. But that’s pretty easy and only mildly illuminating. What do you do to follow up?”

What we need is a way to use the theme of design systematically as a tool for understanding knowledge. To put this another way, we need a theory of understanding reflecting the theme of design. And perhaps there is one. Here are four questions that help in prying open the nature of any design.

- What is its purpose (or purposes)?

- What is its structure?

- What are model cases of it?

- What are arguments that explain and evaluate it?

Consider, for instance, an ordinary screwdriver. Here you know the answers. You certainly know about purpose: It’s for turning screws. Other purposes could be mentioned too, such as prying open paint cans, but we focus on the most common purpose here.

As to structure, you can give me a general description of it, outlining its major parts and materials —the plastic or wooden handle, the metal shaft, the flat tip, and so on. In general, the term structure is used loosely and broadly to mean whatever components, materials, properties, relations, and so on, characterize the object in question. As with purpose, there may be different ways of describing structure; we simply pick one that is natural and illuminating in the context.

As to models, you can show me or draw me examples of screwdrivers. You can demonstrate how to use one. In general, a model exemplifies in some concrete way the design or how it works.

As to arguments, you can explain why it should work. In particular, the handle lets one grip and twist. The flat tip nests into the screw and allows one to turn it. You can also give some pros and cons about its design. For instance, sometimes an ordinary screwdriver does not provide enough leverage to turn screws in hardwood. Sometimes it slips and scars a wood surface. Note that under evaluation we include side effects pro or con, such as scarring wood, as well as effectiveness in the principle objective, turning screws. In summary, your understanding of the design of an ordinary screwdriver includes knowledge about purpose, structure, models, and argument.

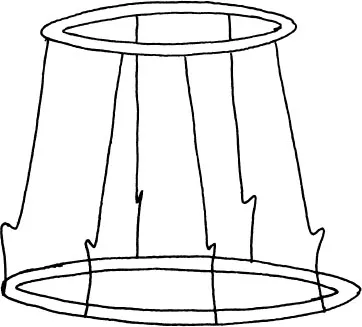

Moreover, if you do not understand those four things about a design, you do not understand the design fully. For instance, consider the sample design in Figure 1.1. The pictured model lets you see much of the structure of this design. Here is some further information about its structure: It is made entirely of steel and has a width of about six inches at the bottom.

Fig. 1.1. A mystery design

Even with all this information, however, you probably do not feel that you understand the design, because you do not have answers to the questions about purpose or arguments. As to purpose, the gadget is a toaster, designed to hold toast over a gas burner. That much of a clue probably lets you figure out some arguments for yourself. Why should it work? The gas flame will toast the pieces of bread as they sit against the wires, supported by the bends near the bottom. With another moment of thought, you can begin to see some pros and cons. For instance, one has to turn the bread in order to toast both sides.

As in this example, so in general: It appears that understanding a design thoroughly and well means understanding answers to the four design questions. Note that there is nothing very novel or esoteric about this notion. The four design questions simply articulate the sort of understanding we all achieve about such ordinary objects as scissors, thumbtacks, belts, shoes, and chairs. They also spell out points we commonly pay heed to when teaching and learning in many concrete contexts such as carpentry or motor repair. The four design questions offer a guide to doing more consciously and carefully what we often do intuitively anyway.

But do the questions apply to a piece of knowledge as well as they apply to a screwdriver? The issue is crucial, since we need a theory of understanding that encompasses knowledge of all sorts, from the most concrete to the most abstract. Let us test the matter. For a first example, consider your knowledge of what a traffic light means. The knowledge has a purpose: to allow you to judge when it is safe and legal to proceed. It seems natural to interpret the structure of the knowledge as these constituent rules: Green means go; red means stop; yellow means proceed with caution. You can give models of the knowledge —a picture or a demonstration at the next traffic light. And, finally, you can give arguments for the utility of having such rules —the arguments of experience or a citation of the legal code, for two instances.

Perhaps the design questions suit such pragmatic knowledge as what to do at a traffic light but not more abstract knowledge. Consider Newton’s laws again. One certainly can ask after purpose —to integrate and explain data about the motions of bodies from baseballs to planets. A useful rendering of structure would be the laws themselves, considered one by one. (Instead, you could take the component words of the laws as the elements of structure, but this would not be an illuminating choice; if you pick the individual laws as your elements of structure you can ponder under argument how each law contributes to the ensemble, but if you pick each word you choose a grain too fine to allow an illuminating account of the whole). Model cases include the solar system and how the laws explain the orbits of the planets. Arguments include an explanation of how the laws work together to give a complete account of a range of dynamic phenomena and an evaluation of the evidence for and against Newtonian mechanics.

Simple facts seem the hardest sorts of knowledge to view as design. Will the design questions serve there? Consider the fact that George Washington was the first president of the United States. This piece of knowledge could have various purposes, one of the most important being to give us an anchor point in history, as with Columbus’s “1492” mentioned earlier. Classifying historical events by presidential administration is a neat way to organize the course of American history. As to structure, it may be useful to think of two components: “George Washington,” which identifies a certain individual, and “first president of the United States,” which identifies a role that individual played. Regarding models, one can find movies and books that dramatize the period and Washington’s presidency. We also have complex mental models of what it is to be a president — the responsibilities, benefits, power, and so on. Regarding arguments, we have plentiful evidence that Washington was indeed the first president, and we can explain how this fact might help us to organize our historical knowledge by providing an anchor point.

Furthermore, as i...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The Giving and Getting of Knowledge

- Chapter 1. Knowledge as Design

- Chapter 2. Design Colored Glasses

- Chapter 3. Words by Design

- Chapter 4. Acts of Design

- Chapter 5. Inside Models

- Chapter 6. Inside Argument

- Chapter 7. The Art of Argument

- Chapter 8. Schooling Minds

- Notes

- Sources

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Knowledge As Design by David N. Perkins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & History & Theory in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.