eBook - ePub

Higher Education by Design

Best Practices for Curricular Planning and Instruction

- 268 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Faculty in higher education are disciplinary experts, but they seldom receive formal training in teaching. Higher Education by Design uses the principles of design thinking to bridge this gap through practical examples and step-by-step instructions based on educational theory and best practices in pedagogical and curricular development. This book offers practical advice for effective teaching and instruction, interdisciplinary curricular collaborations, writing course syllabi, creating course outcomes and objectives, planning assessments, and building curricular content. Whether you are a seasoned professor or new instructor, the strategies in this book can improve your practice as an educator.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Higher Education by Design by Bruce M. Mackh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Beginning With the End in Mind

Chapter Summary

- Educational Philosophy

- Backwards Design: Beginning With the End in Mind

- Learning-Centric Teaching and Instructional Design

- Empathy, Definition, Ideation, and Iteration

- Where Next?

- The Design Process

Higher education is populated by dedicated professional educators who deliver a high-quality academic experience to their students. However, professional development activities related to teaching are usually limited to occasional workshops featuring a single skill, such as creating a syllabus, techniques for assessment, or new instructional technologies. Many of us attended required onboarding seminars for new faculty members that provided basic instruction in the teaching component of our jobs. Nevertheless, no matter how many workshops or seminars we attend, or how experienced we may be, it is not the same as undergoing a formal program of study into the art, science, practice, and skill of teaching.

Faculty members come to their positions as subject-matter experts, having earned the highest degrees available in their respective fields and achieving recognition as producers of new knowledge through research or contributors to culture through creative practice. In fact, these are standard criteria for virtually all faculty job postings. Members of the professorate continue their disciplinary activity throughout their professional lives, with an expectation that each person will make ongoing contributions to knowledge or culture.

Furthermore, all faculty members are educators because we teach students the essential skills and knowledge of our academic disciplines. Our achievements in research or creative activity strengthen this expertise, which we then bring to our classrooms. Professional service further supports our disciplines and our college or university, consequently enriching our teaching as well.

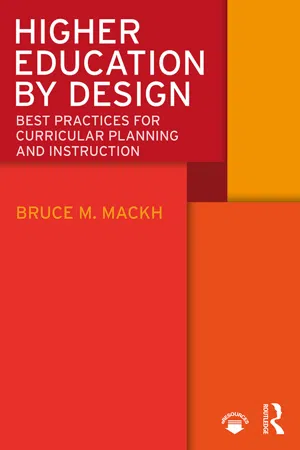

Traditional evaluative criteria for promotion and tenure generally split faculty activities into 40% for research, 40% for teaching, and 20% for professional service, but in actual practice, we often spend the majority of our time teaching or on related tasks such as course development, grading, and meeting with students. According to the National Study of Postsecondary Faculty (2003),1 teaching and related tasks account for 62% of faculty members’ time, with 18% spent on research and 20% on administrative or other tasks. All of these activities ought to work in concert, and all of them ultimately support the success of our alumni as well as contributing to knowledge and culture. Even when research is valued above all other faculty pursuits (which is especially evident at top-tier research universities), it also contributes to our graduates’ success across disciplines, as shown in Figure 1.1.2

Research, teaching, and service each contribute to student learning and our graduates’ eventual success, either directly or indirectly.

- Research builds upon existing knowledge to create new learning.

- Teaching improves and expands student learning.

- Service translates learning into action that improves communities and citizens.

Isn’t it curious, then, that we seldom undergo formal training in educational theory or in curricular and pedagogical development, despite the demonstrable importance of our responsibility to teach? Yet instead of the prerequisite study and certification required of many other educators, faculty members typically learn to teach by teaching, sometimes assisted by colleagues and mentors in our academic disciplines.

Speaking from my own experience, the only preparation I received for the first course I taught as a graduate instructor occurred when my academic advisor handed me a copy of the former instructor’s syllabus. He answered my questions and dropped by my classroom on occasion, but for the most part, I was on my own. At the institution I attended for my doctoral studies, graduate instructors were first required to serve as teaching assistants, a task mainly involving taking attendance and grading papers for the instructor of record. Once we were given a teaching assignment of our own, a copy of the previous instructor’s syllabus and perhaps some verbal advice were treated as sufficient preparation for independent teaching. I opted to take my training a step further by participating in a TEACH Fellowship, a competitive program offered through the university’s Teaching, Learning, & Professional Development Center.3 This yearlong experience included 18 hours of workshops, videotaped consultations, two midterm evaluations of teaching performance, completion of a teaching portfolio and curriculum design project. None of the other graduate instructors in my program chose to take this step, but I found it to be a valuable asset to my subsequent teaching both then and in my later faculty positions.

Figure 1.1 Organizatonal Chart of Research

This book was written as a way to bridge the gap that I observed between the actual practice of teaching and the knowledge that can be gained through focused formal study. As a comparison, consumer electronics have advanced to such high levels that we can use them intuitively right out of the package. Even so, many of us have experienced moments of frustration where we can’t make a device do what we want it to do, wishing it had come with a detailed user’s manual. Author David Pogue and O’Reilly Media produce a series of publications in response to this need—the “Missing Manuals”—beginning with Windows 2000 Pro: The Missing Manual and most currently Switching to the Mac: The Missing Manual, El Capitan Edition (2016).4 I’d like you to consider this book in the same spirit—to be the guide for teaching in higher education that most educators never received when we were given our first teaching assignments. The chapters that follow will help those at all levels of experience to design, develop, and deliver excellent educational content to their students.

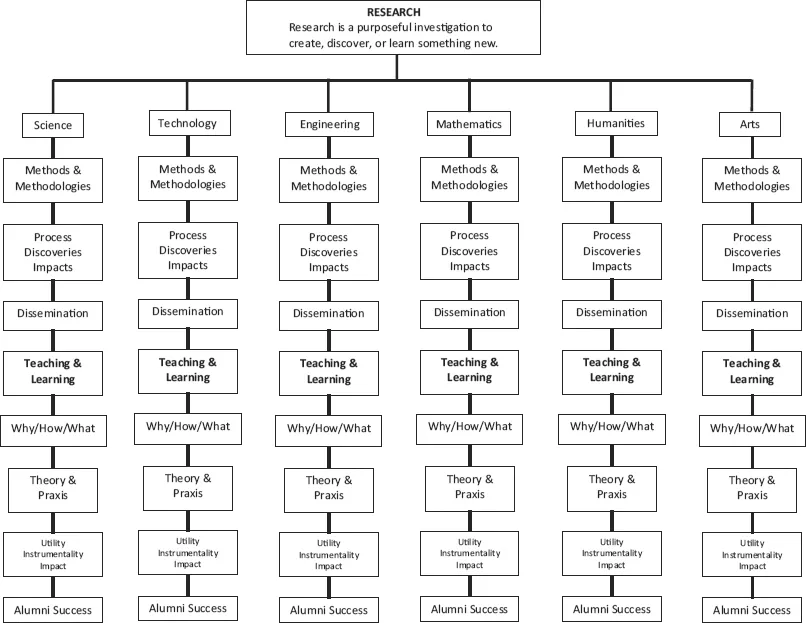

Educational Philosophy

Much of what we do in our classrooms depends on how we view our role as instructors. You’re probably familiar with the debate between an instructor’s role as “a sage on the stage” or “a guide on the side.” Some instructors remain firmly in the sage-on-the-stage camp, lecturing through every class period, while students listen attentively and take copious notes. Conversely, other instructors rarely lecture at all, allowing students to construct knowledge independently, intervening only when the student requests assistance.

This need not be an either/or proposition. Most courses utilize a variety of instructional strategies, including lecture, project-based learning, discussion, group activities, and more. We might visualize this as a dual continuum as illustrated by Figure 1.2: the more active the instructor, the less active the student; the more active the student, the less active the instructor.

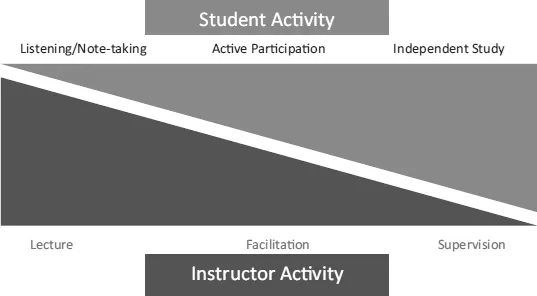

Another common debate involves the philosophical orientation of the classroom toward an instructor-centered or student-centered model. An instructor-centered classroom operates under the assumption that the instructor possesses knowledge that she transmits to the students through a one-way communication. The instructor is responsible for his or her teaching, and students are responsible for their own learning. In contrast, a student-centered classroom places the student at the forefront of this equation, but this might raise troubling issues such as whether the student is a consumer of education and what responsibility the instructor shares in the student’s acquisition of knowledge. For example, under a completely instructor-centered model, a student who fails a course is wholly responsible for his own failure. However, under a completely student- centered model, the instructor might be deemed to have failed to provide adequate instruction rather than the student failing to learn.

Figure 1.2 Student–Instructor Continuum

Taking a learning-centered approach avoids the problems of these extremes. In this model, students are neither passive recipients of transmitted knowledge, nor are they demanding clients. Likewise, the instructor is neither the font of all knowledge nor the students’ servant. The focus of a learning-centered classroom is the subject matter of the course as it occurs within a specific disciplinary context, engaging both the student and the instructor as active participants. We might frame learning-centered education as a pedagogical triangle (see Figure 1.3), in which the student, instructor, and subject matter exist within a balanced yet dynamic relationship occurring in the context of a given academic discipline.

Therefore, this book adopts a learning-centered educational philosophy. The instructor’s primary responsibility is to create and deliver a learning experience in which the student is an active participant, aligned with a particular academic discipline’s norms and practices and shaped by the instructor’s application of skill and knowledge in teaching.

Figure 1.3 Pedagogical Triangle

Backwards Design: Beginning With the End in Mind

In his bestseller Seven Habits of Highly Effective People, author Stephen Covey recommends “Habit 2: Begin with the End in Mind.” 5 Even though it’s become somewhat cliché, this isn’t just good advice for life—it’s the first step toward planning and designing effective curriculum. Beginning with the end in mind is like planning an expedition: First, you choose the destination, then you plan how you’ll get there.

In curriculum design, our destination depends on this question: What skills and knowledge should our students acquire by the time they graduate? Just as we can’t take a road trip without first planning our route, we can’t achieve the goal of producing well-educated graduates unless each course deliberately aligns with that goal, leading students step by step toward the excellence we want them to achieve. When applied to higher education, this is called backwards design.6

Before we go further, let’s stop and consider why we’re talking about this. In higher education, where colleges and universities have clearly defined educational missions, we want our students to do more than just memorize facts—we want them to become accomplished disciplinary practitioners who contribute to our areas of expertise and go on to lead successful, productive lives. We also want to enhance our institution’s reputation for excellence in education and raise the profile of our college and its programs and departments. Therefore, the end we should keep in mind exists on multiple levels: in the outcomes we write that explain what our students must know and be able to do by the time they graduate; in the learning experiences we design that facilitate our students’ successful attainment of these outcomes; and in the deepening of our knowledge of educational theory and philosophy that will allow us to improve in our instructional delivery and better fulfill our duty as educators.

Understandably, research and creative practice receive a great deal of emphasis as major contributors to our professional reputations and the status of the institutions where we teach, whereas excellence in teaching lacks comparable prestige. Nevertheless, the impact of our teaching extends far beyond the final exam, shaping our students’ academic experience for good or ill. No matter how renowned we may be in our chosen fields, these accomplishments cannot benefit our students at all if we lack the ability to translate our disciplinary expertise into relevant and impactful instruction. Shouldn’t we, therefore, devote at least as much passion, energy, and curiosity to our teaching as we do to our other disciplinary engagements?

Nothing prohibits us from continuing to teach as usual. Attempting to change our professorial habits is a far greater challenge, yet there is much to be gained in the attempt. Certainly, it can be awkward and frustrating to change longstanding habits, but by choosing to reach beyond what’s comfortable to what’s possible, we will benefit our students, our institutions, and ourselves as well.

Learning-Centric Teaching and Instructional Design

Traditional approaches to teaching and learning focus on the subject-matter knowledge and expertise that an instructor conveys to his or her students. When we shift the emphasis to our students’ learning, we must also enter into a mindset of innovation since we are diverging from long-established procedures and habits of mind in higher education.

Innovation exists within a three-part framework, represented in Figure 1.4.

Desirability is the human factor in innovat...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Preface

- eResources

- 1 Beginning With the End in Mind

- 2 Understanding Educational Theory

- 3 Creating Course Outcomes and Objectives

- 4 Assessing Student Learning

- 5 Planning for Effective Instruction

- 6 Writing as Instruction and Assessment

- 7 Incorporating Engaged Learning

- 8 Teaching Effectively

- 9 Planning for Interdisciplinary Collaboration

- 10 Meeting 21st Century Challenges: Synthesis and Application

- 11 Becoming the Educator You Want to Be

- Epilogue

- Index