- 228 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Archaeology of Early Rome and Latium

About this book

The archaeology of early Rome has progressed rapidly and dramatically over the last century; most recently with the discovery of the shrine of Aeneas at Lavinium and the reports of the walls of the Romulan city discovered on the city slopes of the Palatine Hill. The Archaeology of Early Rome and Latium presents the most recent discoveries in Rome and its surroundings: princely tombs,inscriptions and patrician houses are included in a complete overview of the subject and the controversies surrounding it.

This comprehensively illustrated study fills the need for an accessible English guide to these new discoveries, and in preparation, the author interviewed most of the leading figures in current research on the early periods of Rome.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Archaeology of Early Rome and Latium by Ross R. Holloway in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

INTRODUCTION

When, during the last two centuries of the Roman Republic, the first writers of Roman history, collectively known as the annalists, set about their task, they looked back into a fog.1 Here and there a landmark seemed to emerge from the mists of time. The most prominent of these was the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill (figs 1.1, 1.2). This temple, 62 m (203.3 ft) in width, rivaled, in this dimension at least, the temples of the richest Greek cities of Asia Minor or Sicily. It was reputed to have been raised by the kings of the sixth century BC and dedicated in the first year of the Republic, 509. Inscriptions dating to the centuries before 387, another landmark year in the history of Rome when Gauls from the Po Valley were said to have defeated the Roman army and sacked the open city (while the Capitoline alone held out and was eventually relieved), were few and difficult to understand. A list of magistrates with a sprinkling of events from their years of office was compiled in the late second century by the chief Roman priest, the Pontifex Maximus (the Annales Maximi).2 The reliability of the state records on which it was based can only be conjectured. Livy thought that none survived from before the Gallic disaster.3 And even following the redaction and reconstruction of the second century, differing traditions remained, as can be seen from the discrepancies among the main continuous sources, Livy (59–AD 17), Dionysius of Halicarnassus (in Rome after 30), Diodorus Siculus (active 60–30) and the Fasti Capitolini, the list of consuls (Fasti Consulares Populi Romani) and of the victorious generals accorded a triumph (Fasti Triumphales Populi Romani), which was set up in the Forum under Augustus.4 The family traditions of the great houses of Rome, embodied in the funeral orations for their various members, were no better guide to the past. Cicero’s opinion (Brutus XVI, 62) was especially unflattering: “These orations have left the history of our state full of lies. There are many things written in them which never happened, bogus triumphs, duplicated consulships, faked genealogies whether by (patrician) assumption of plebeian status or when men of lower condition are mixed up with another family of the same name.”5 An inscription recording the prominent ancestors of an Etruscan family of Tarquinia and their deeds in the fifth to the third century BC has been cited as an example of such fasti.6 But it does not answer Cicero’s charge of exaggeration and falsification. Still less reliable as historical sources would have been the Roman banquet songs telling of the feats of olden days. Not one scrap of these has been preserved, but banquet songs appealed strongly to nineteenth-century historians as a possibly genuine source for early Roman history.7

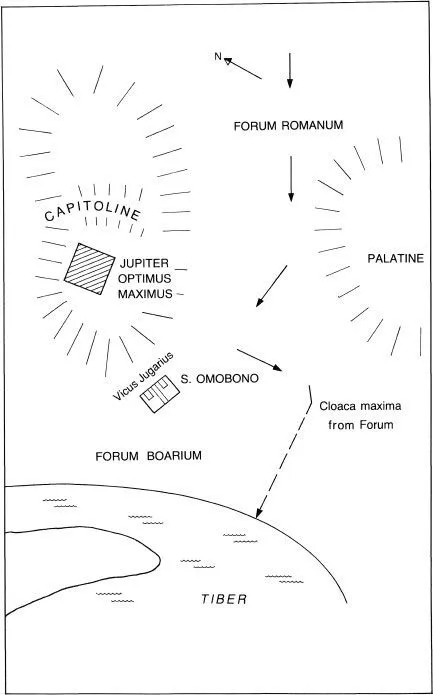

Figure 1.1 Rome, area of the Capitoline, Velabrum Valley, and Forum Boarium.

The earliest annalists, Fabius Pictor and Cincius Alimentius, both men of importance during the period of the Second Punic War, wrote in Greek for a Greek audience with the intention, it appears, of countering Carthaginian propaganda in the face of Rome’s rise to world power. Their works, like those of the other annalists, have perished and are known only from meager quotations and comments of later historians. To judge from the number of chapters (“books”) in their works dedicated to early times, they got over early Rome quickly. For the early periods of the city’s history they were able to draw on the writings of a large group of Greek historians going back to the Sicilian authors of the fifth century and culminating in Timaeus of Tauromenium (third century) who treated Rome in his account of the history of the west. Much of the embellishment of Roman legend must be due to these Greek sources. The second and third waves of the Roman annalists, now using Latin and so writing for an exclusively Roman audience, produced ever more voluminous accounts of early Rome from the same sources, domestic and foreign, that had been used by their predecessors. Artifice and imagination, often stimulated by the urge to glorify one’s own clan and vilify others, were hard at work. According to Livy (XXX, 19, 11) one of the later annalists, Valerius Antias, wrote “Shamelessly as to facts, negligently as to omissions.”8

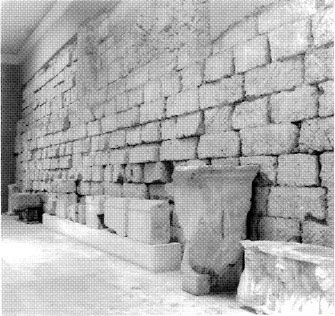

Figure 1.2 Rome, Capitoline, foundations of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus visible in the Palazzo dei Conservatori, Museo Nuovo.

Such is the background of the connected histories written under the reign of Augustus (27–AD 14) by two rhetoricians, Livy and Dionysius of Halicarnassus. They could not improve on their sources, although Livy, in particular, freely admitted his distrust of them. Livy was writing not as an historian in the modern sense of the word but as a moralist recounting history for the edification of his audience. Dionysius wrote for his Greek readers (which would include all educated Romans of the day) in a similar vein, with less power than Livy and with an unrestrained talent for composing artificial speeches.9

In modern times the inconsistencies and improbabilities of the history of the kings and of the early Republic (the archaic period of Rome) were noted not long after readers had printed copies of the classical texts in their hands.10 After 1800 higher criticism, already at work in the study of the holy scriptures, found another fertile field in early Rome. What Niebuhr began in 1826 Ettore Pais finished a century later.11 In the view of these scholars, argued with searching detail and no small dose of common sense, early Roman history was largely a fabrication, romanticizing the few traces of real tradition with Greek trimmings. It catered to the vanity of prominent families of the late Republic, inflated the importance of the small city of archaic times and disguised the military weakness of the Romans in confronting their nearby enemies. The Augustan historians, moreover, were unable to conceive of political history without the demands for land distribution that drove the motor of Roman politics at the end of the Republic and the rivalries of the patricians and plebeians as these social orders existed in the same period. The great Mommsen wrestled with the problem of early Roman traditions, but when he came to write his general Römische Geschicbte12 he decided that the early centuries of Rome were too uncertain to be presented in narrative form.

Neither Pais nor Mommsen held a high opinion of the usefulness of archaeology as a tool of ancient history. But in recent decades archaeology has played a decisive role in the study of early Roman history because, as the rediscovery of remains of ancient Rome and Latium between the tenth and fifth centuries BC expanded, it encouraged a more sanguine view of the Roman historical tradition. The antiquity of settlement at Rome was first proved in a convincing fashion by Giacomo Boni’s discovery of the Iron Age cemetery of the Roman Forum in the years between 1902 and 1911.13 If the Romans of Romulus’ time had their tombs in the Forum valley, the houses of the same period could not be far away, and indeed they were soon to come to light on the Palatine Hill.14 The historicity of the Etruscan kings also emerged, it seemed, in material form. In 1899 Boni discovered the archaic cippus (stone upright) with inscription below the square of black stones set in the paving of the Roman Forum during the High Empire to mark the spot, according to widely accepted tradition, where Romulus was buried.15 The fact that one of the few words read by all scholars in the truncated inscription, which is written in bafflingly archaic Latin, was rex (king) became a powerful weapon in arguing for the reality of the Rome of the kings. In fact, in the early twentieth century there was developing a compromise position among historians, associated particularly with the names of Beloch and De Sanctis, less critical of the received tradition than Niebuhr and Pais and willing to accept much of it in a reconstruction of early Roman history.16 Some scholars, encouraged by archaeological discoveries, went further. At the end of the 1920s Mrs Ryberg wrote of the “Essential correctness of the Romans’ own traditions concerning their earliest history.”17 And in 1936 G. Pasquale was riding the crest of the historical wave when he published his essay “La grande Roma dei Tarquinii” (The Great Rome of the Tarquins).18

Two years later a discovery was made which seemed to reveal regal Rome in all its splendor: the early levels (seventh to fifth centuries) underlying the twin temples discovered in 1937 below and beside the church of Sant’Omobono just below the Capitoline Hill and along the road from the Roman Forum to the Tiber and the cattle and produce markets located on the river bank (Forum Boarium and Forum Holitorium) (fig. 1.1). The excavator, A. M. Colini, immediately identified the twin temples of the later ancient phase of the site as the temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta (Aurora) known to have stood in the Forum Boarium and often mentioned together.19 When an archaic temple was discovered beneath one of these shrines, its first phase datable before 550, this was assumed to be the temple of Mater Matuta of King Servius Tullius.

Finally, the grand work of archaeological synthesis carried out by Einar Gjerstad accepted the new interpretation, differing from it only in the dates assigned to the various phases.20 The general movement to revise Gjerstad’s “low chronology” has cancelled even his modifications of the ancient tradition and has now given us works in which archaeology marches hand in hand with the annalists from Romulus to Tarquin the Proud.21

One of the most important archaeological discoveries bearing on early Roman history also brings out the nature of the problems connected with these traditions with great clarity. In 1857 the explorer of Etruscan cemeteries Alessandro François discovered the tomb at Vulci that now bears his name.22 The frescoes from the François Tomb passed into the collection of the Villa Albani in Rome and have never been on public view. They belong to the fourth century and are composed of two sections, which were displayed around the walls of a single chamber. Both serve to satisfy the Etruscan need for blood to honor the dead, a desire which encouraged the repetition of the most gory episodes from the repertoire of Greek mythology in their funeral art. On one wall and part of another the hero Achilles is seen slaughtering the Trojan captives at the grave of Patroclus, while Eteocles and Polyneices, among other scenes, engage in their mutually destructive duel. The corresponding paintings are similarly sanguinary but are not drawn from Greek mythology. Rather, their subjects are Etruscan. A figure labeled as Cneve Tarchunies Rumach (Gnaeus Tarquinius Romanus) is being attacked by Marce Camitlnas (Marcus Camillus?). Then across from the Homeric sacrifice to Patroclus a warrior labeled Macstrna (Mastarna) is found freeing one Caile Vipinas (Caelius Vibenna) from chains. Next come three duels to the death. Larth Ulthes runs through Laris Papathnas Velznach (Volsinii?). Rasce comes against Pesna Arcmsnas Sveamach (Sovana?) and Aule Vipinas kills Venthicau … plsachs. Despite the reference to Rome and Etruscan cities the significance of these encounters between Etruscan and at least one Latian champion would be lost on us were it not for the appearance of Mastarna and the brothers Vibenna, who were also known to Roman history.

The sources for early Roman history to whom we now turn are unusual but important. They include some of the best minds of the late Republic and Empire: Varro, the pioneer student of the Latin language and Roman institutions (116–27), the Emperor Claudius (10–AD 54), who was plucked from a life of scholarship to assume the Imperial purple and whose specialty was Etruscan antiquity, and finally, Tacitus, the Roman Thucydides (ca AD 56–post AD 113). According to Tacitus (Ann. IV, 65) the Caelian Hill, once known as the Querquetulanus (from the oak trees growing there), had been renamed when Caelius Vibenna, an Etruscan captain, settled there in the time of Tarquin the First or perhaps under another of the kings. Claudius, whose remarks come down to us in an inscription which gives the text of a speech by the Emperor, noted that King Servius Tullius was an ally of Caelius Vibenna (CIL XIII no. 1668). After the latter’s death the king brought the remnants of his followers to Rome and settled them on the hill renamed in his honor. Servius himself had former...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of illustrations

- Preface and acknowledgments

- Basic bibliography

- Abbreviations

- 1 INTRODUCTION

- 2 TOMBS OF THE FORUM AND ESQUILINE

- 3 CHRONOLOGY

- 4 HUTS AND HOUSES

- 5 THE SANT’OMOBONO SANCTUARY

- 6 THE LAPIS NIGER AND THE ARCHAIC FORUM

- 7 WALLS

- 8 OSTERIA DELL’OSA

- 9 CASTEL DI DECIMA; ACQUA ACETOSA, LAURENTINA; FICANA; AND CRUSTUMERIUM

- 10 LAVINIUM

- 11 SATRICUM

- 12 PRAENESTE

- 13 CONCLUSION

- Notes

- Index