![]()

Chapter 1

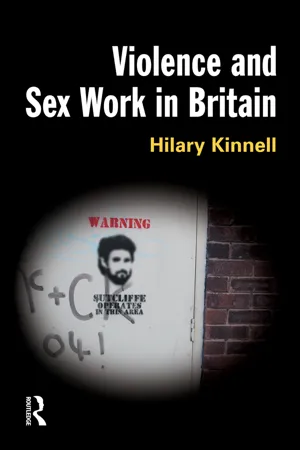

Peter Sutcliffe: a long shadow

Between 1975 and 1980 Peter Sutcliffe, a lorry driver living in Bradford, West Yorkshire, attacked and murdered women, some of whom were sex workers. Most of his known crimes were committed in Yorkshire, hence the sobriquet he acquired long before his arrest – ‘the Yorkshire Ripper’. The West Yorkshire police wrongly assumed that the culprit they sought was primarily motivated by hatred of prostitutes; when other, ‘innocent women’ were also attacked, intense fear and anger was felt by numerous women living in the area, and public disquiet with the failure of the police investigation became increasingly vociferous. The investigation was also seriously misdirected in the last three years by hoax letters and a tape made by someone with a strong ‘Geordie’ accent, who claimed to be the murderer, so convincing the police that the killer was from the North East.1 Sutcliffe was eventually arrested in January 1981, subsequently confessing to killing 13 women and attempting to murder another eight. At trial he pleaded not guilty to murder on the grounds of diminished responsibility, claiming to have heard the voice of God directing him to kill prostitutes. Sutcliffe's defence claimed that he suffered from paranoid schizophrenia, genuinely believed he heard such ‘voices’ and was therefore insane, not guilty of murder. This defence was rejected by the jury, finding Sutcliffe guilty of murder, although psychiatrists later reiterated their diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia, whereupon he was transferred to Broadmoor, where he remains.

Revisiting the macabre Sutcliffe circus, I have used Deliver Us from Evil (Yallop 1981), which has the immediacy of a text written contemporaneously with the events described and covers much more than the appalling details of the crimes and stupefying ineptitude of the police investigation. Yallop also gives a vivid account of the street soliciting areas of West Yorkshire in the 1970s, the way policing of street prostitution changed, or did not change, as the toll of victims mounted, and the emergence of a new kind of feminist activism which sparked widespread protests about violence against women. Bilton's more recent account (Wicked Beyond Belief 2006) at times reads like a 600-page exoneration of the West Yorkshire police2 but is undoubtedly comprehensive. I have also visited websites devoted to the subject3 and read those parts of the report on the official review of the police investigation as have been made public (Byford 1981). My knowledge of the facts about the case is based on these sources. Also, in exploring the paths by which Sutcliffe's activities became incorporated into the version of radical feminist ideology which currently dominates debates on prostitution, I have examined a number of feminist texts which were written during or soon after the Ripper era. In this I am traversing territory already covered by Walkowitz (1992), but my focus is less on developments in feminist ideology, more on the actions of those who professed this ideology and the implications of their ideology for current policy towards sex work.

Sutcliffe's crimes continue to exert a profound influence on public perceptions of violence in the sex industry; they are frequently referenced in media reports of sex worker murders, while some rapists and murderers apparently seek to achieve notoriety by emulating his example.4 Reverberations from the Sutcliffe era can also be discerned in contemporary policing of street prostitution, in today's debates about prostitution policy and in radical feminist constructions of violence against sex workers. These aspects of the Sutcliffe story need to be understood; their impact on contemporary thought about and policy towards prostitution needs to be recognised, so I hope the survivors among Sutcliffe's victims and their relatives will forgive me for drawing attention to events which cannot but cause immense pain (McCann 2004).

Sutcliffe's victims

Sutcliffe is still regarded primarily as a prostitute-killer, despite the fact that many of his victims were not sex workers. Does it matter? I think it does, partly because characterisation of all Sutcliffe's victims as sex workers caused and must continue to cause distress to survivors who were not sex workers and to the families of non-sex workers who died. The Telegraph website referred to Sutcliffe murdering ‘13 prostitutes’ in February 2008.5 A ‘true crime’ television programme in January 2008 6 named some of Sutcliffe's non-sex worker victims, without making clear that they were not sex workers, while Wilson (2007) uses Sutcliffe as the paradigm of a serial killer who targets sex workers but profiles one of his non-sex worker victims without examining what made her also vulnerable. The ‘Sutcliffe-as-prostitute-killer’ myth also sustains present-day assumptions that people who kill sex workers do not present a danger to non-sex workers, and disguises the factors which did contribute to his victims’ vulnerability.

Among Sutcliffe's victims the only uniting factors were that they were alone outside at night and they were female. Their ages ranged from 14 to 47; some – both sex workers and non-sex workers – had had a drink, some had had several, others were stone cold sober. Their occupations included schoolgirl, shop assistant, civil servant and postgraduate medical student; some were regular sex workers, but several of those categorised by police as sex workers had no convictions for soliciting, and in some cases the only evidence that the victims had been soliciting when they were attacked came from Sutcliffe himself.

Sutcliffe's first acknowledged victims were Anna Rogulskyj (July 1975, Keighley), Olive Smelt, (August 1975, Halifax) and Tracey Browne, a 14-year-old schoolgirl (August 1975, Silsden).7 They all suffered terrible head injuries, but survived. None was a sex worker and none was in or near a ‘red-light’ district when attacked, but the pervasiveness of misrepresentations about Sutcliffe's victims and about police failures continue to this day: Harrison and Wilson (2008) compare the attacks on Rogulskyj and Smelt to Sutcliffe's earliest known attack on a sex worker (in 1969), indicating that they were also sex workers and in ‘red-light’ districts when attacked, while the television programme cited above also implied that these attacks happened in ‘red light’ districts and that the police ignored them because attacks on sex workers were so common. Rogulskyj and Smelt were not included as possible victims of the ‘Ripper’ until 1978, and Tracey Browne was never included, despite having provided a detailed description of her assailant and an accurate photofit of Sutcliffe. In later years, feminist writers claimed that police had not taken the deaths among sex workers seriously until non-sex workers were killed, but a more accurate criticism would be of their failure to link these three attacks or investigate them vigorously.8

Sutcliffe's first known murder victim was Wilma McCann (October 1975) in Leeds. She had no convictions for soliciting, but police described her as a ‘good time girl’ who sometimes had sex for money. The strongest evidence that she did comes from Bilton, who states that Wilma was not claiming Social Security benefits despite having four small children. She may have chosen to do without – many sex workers are proud to be independent of state hand-outs – but if she was refused benefits, as women routinely were, if they had men friends with whom they might be cohabiting, sex work may have been a choice of desperation. Even so, the only evidence that she expected money for sex came from Sutcliffe himself. The next murder victim, Emily Jackson (January 1976, Leeds) had sold sex for only a month to pay off family debts and had no convictions for soliciting either, but her death was immediately connected to McCann's and a week later Detective Superintendent Dennis Hoban announced, ‘We are quite certain the man we are looking for hates prostitution … I am quite certain this stretches to women of rather loose morals who go into public houses and clubs, who are not necessarily prostitutes …’9

In May 1976 Sutcliffe attacked Marcella Claxton, again in Leeds. She survived. Police described her as a prostitute, but she did not have any soliciting convictions and later denied that she asked Sutcliffe or anyone else for money for sex. Marcella was said to have learning difficulties, but she gave an accurate description of her attacker. The police, however, ruled this attack out of the series, insisting her assailant must have been a black man, perhaps because Marcella was black herself and had been drinking in a West Indian club earlier that night. It is also possible the police had an eye on the tense race relations in Leeds. Six months earlier, there had been a minor riot in Chapeltown:10 a vice squad car was overturned by a gang of mainly black youths, injuring two officers. A year later, after three more murders, the Assistant Chief Constable, George Oldfield, went on a charm offensive to the black community of Chapeltown, begging for assistance in the enquiry and stating, ‘So far, all the victims have been white’ (Yallop 1981). Marcella's attack was not included in the series until Sutcliffe confessed to it.

Irene Richardson (February 1977, Leeds) had no convictions for soliciting either. She had been working as a cleaner and applying for jobs as a nanny, was homeless, recently abandoned by her boyfriend and had been sleeping in a toilet block. Although it was said that she may have sold sex for survival, on the night she died she told a friend she was going to look for her boyfriend. Again, there is only Sutcliffe's word for it that she asked him for money. She was killed yards from where Marcella Claxton had been attacked, but although police initially connected the two, reinterviewing Marcella and obtaining from her an accurate photofit of Sutcliffe, she was again deemed an unreliable witness. Patricia Atkinson (April 1977, Bradford) did have convictions for soliciting, but witnesses who saw her earlier that night place her getting uproariously drunk in various pubs, not soliciting: evidence that she expected money for sex comes from Sutcliffe.

When 16-year-old shop assistant Jayne MacDonald was murdered two months later (June 1977, Leeds), it was assumed that she had been ‘mistaken for a prostitute’ because she was in an area ‘frequented by prostitutes’. ACC Oldfield emphasised that Jayne was ‘an innocent victim’, and while the police have since been pilloried for making this invidious distinction, their apparent attitudes precisely reflected those adopted in the press.11 The police were also frustrated by the lack of public assistance in the enquiry into murders of prostitutes, and hoped Jayne's death would provoke more response. It did, as Byford commented:

MacDonald's youth and the fact that she was not a prostitute produced rather more response from the public and media interest sharpened in consequence. Both the police and the press expressed the view that the killer might have made a mistake and wrongly identified MacDonald as a prostitute. The possibility that any unaccompanied woman was a potential Ripper victim was not considered at that time. (Byford Report 1981: para. 313)

At this stage police began checking earlier attacks on non-sex workers, but the attack on Marcella Claxton was still excluded from consideration. Only two weeks after the murder of Jayne MacDonald, Maureen Long was attacked: she survived. She was not a prostitute but was nevertheless described as ‘acting as a prostitute’ (Byford Report) because she accepted a lift from a stranger after a night out and because Sutcliffe claimed she seemed willing to have sex with him.

The next four known attacks were on sex workers. Three died: Jean Jordan (October 1977, Manchester) who had cautions for soliciting but no convictions; Yvonne Pearson (January 1978, Bradford), and Helen Rytka (January 1978, Huddersfield), who also had no convictions. The fourth was Marilyn Moore (December 1977, Leeds) who survived, and gave an accurate description of Sutcliffe. The resultant photofit was seen by Tracey Browne, attacked two years earlier. Tracey went back to the police insisting that she had been attacked by the same man, but she was not taken seriously. Unfortunately Moore's recollections about her attacker's car were less accurate, and it was the car description that the police followed up assiduously, regarding her description of the man as unreliable.

Vera Millward, who was 40, died in May 1978, in Manchester. Her most recent soliciting conviction was five years earlier, and it was believed she had only one regular client whom she may have expected to meet the night she died, but he did not turn up. Perhaps she solicited Sutcliffe, as he claimed, since her regular had let her down, but she was also a sick woman, suffering from chronic stomach pains, and Bilton suggests she was making her way to the casualty department of the very hospital in whose grounds she died when Sutcliffe offered her a lift. Vera was the last sex worker to die at Sutcliffe's hands, and possibly the last sex worker he attacked. After Vera, in the 19 months from May 1978 to his arrest in January 1981, all Sutcliffe's known victims were non-sex workers. Four died: Josephine Whitaker, 19 (Halifax, April 1979); Barbara Leach, 20 (Bradford, September 1979); Marguerite Walls, 47 (Pudsey near Leeds, August 1980); and Jacqueline Hill, 20 (Leeds, November 1980). Two survived: Uphadya Bandara, 34 (Leeds, September 1980), and Teresa Sykes 16 (Huddersfield, November 1980).

The Byford Report

While many police officers today were not born until after Sutcliffe was convicted, it seems likely that the institutional memory of that terrible debacle still resonates within the service. Referring to it in an article about unsolved sex worker murders in 1995, Bilton wrote:

Few outside the police service can imagine the professional shock waves that resulted from this very public humiliation, not least the severe embarrassment and alarm felt among higher ranks when the then Home Secretary, Willie Whitelaw,12 told MPs in January 1982 of the litany of serious errors of judgment made during the five year murder hunt. (Bilton 1995)

Whitelaw's statement concerned the findings of Her Majesty's Inspector of Constabulary, Lawrence Byford, appointed to undertake a review of the Ripper investigation in May 1981, four days after Sutcliffe's trial ended. Byford presented his report to Whitelaw in December the same year, but despite calls by MPs for it to be made public, it was deemed so sensitive, so likely to cause catastrophic loss of public confidence in the police and to worsen the already damaged morale of the West Yorkshire force, it was not made public until 2006. Some parts of it are still not public.13 Even more extraordinary, although stuffed with useful recommendations about the investigation of major serial offences, it was not made available to senior police officers, not even chief constables. At first Byford strenuously objected to this secrecy, but was assured that its recommendations would be addressed by the Home Office through training for senior officers and by provision for adequate computer support (Bilton 2006).

Byford's main criticisms related to the inadequacy of the information systems to deal with the deluge of paperwork generated by the massive enquiry, the lack of effective overall management, the casual attitudes of junior officers tasked with routine enquiries, some terrible blunders in handling the media and poor judgement in their reliance placed on the hoax letters and tape. However, Byford also stated:

With the additional benefit of hindsight it can now be clearly established that had senior detectives of the West Yorkshire assembled the photofit impressions from surviving victims of all hammer assaults or assaults involving serious head injuries on unaccompanied women, they would have been left with an inescapable conclusion that the man involved was dark haired with a beard and moustache. (Byford Report 1981: para. 572, my emphasis.)

Although I regard Joan Smith's recent foam-flecked demands for the punishment of men who pay for sex as unhelpful and mistaken,14 I agree with her conclusion that the police investigation failed because their perception of the killer as someone who primarily targeted sex workers meant they excluded much valuable evidence arising from his many attacks on non-sex workers (Smith 1989). Byford made the same points, but in his ‘Conclus...