![]()

Chapter 1

Theoretical Foundation for Interactive Art Therapy

For many years, psychotherapy has been thought of as the “talking therapy,” primarily using the auditory sensory modality for interacting with clients. Yet, in recent therapeutic history, professionals have been expanding their repertoire, using other sensory modalities to aid clients in the healing process. Dance and movement therapies, music therapy, therapy using photography, various forms of art therapy, and even a therapy using flowers, have all been developed around our primary senses: seeing, hearing, touching, smelling, and tasting. Although many of these therapies seem to work well with clients from an experiential perspective, not all have been thoroughly researched by any means.

It has been reported that more than 50 percent of our cerebral cortex is devoted to visual functions, while a large part of the remaining cerebral cortex capacity is devoted to auditory functions (Basic Behavioral Science Task Force, 1996). Although experientially I knew Interactive Art Therapy worked with clients, as a professional therapist, I wanted to know why. So I began to look at research that might explain this phenomenon. Certainly, the two sensory modalities of seeing and hearing, which are the focus of Interactive Art Therapy, have garnered the highest proportion of research in this area by far.

DUAL-CODING THEORY

Clearly, the underlying notion of Interactive Art Therapy is the interaction between verbal and visual material. When I read the following quote, I had an “aha” moment: “It also should be noted that, under certain circumstances, verbal material can evoke the construction of visual representations, and visual material can evoke the construction of verbal representations” (Mayer and Sims, 1994, p. 390). This information comes from a growing body of research investigating the interaction of visual and auditory processes in learning.

The term multimodal has been coined to refer to the idea that individuals use more than one sensory modality to learn new material. This concept is part of a larger theoretical framework called dual-coding theory (Mayer and Sims, 1994). Thus far, much of the research done in exploring dual-coding theory has focused on the best way to present academic material to students so they can learn more quickly and retain material longer. In the case of therapy, the new material to be learned and retained is not academic, but new insights into the “why” of behaviors and emotions as well as the development of new coping skills to deal with problematic behaviors and emotions.

The conscious processing of information is necessary to learn new information. It also seems logical to assume that conscious processing is foundational for gaining insight in a therapeutic setting. Conscious processing requires working memory. Recent research suggests that working memory involves the independent functioning of visual processors and auditory processors (Kalyuga et al., 2000; Tindall-Ford et al., 1997). It has also been suggested that the effectiveness of working memory is enhanced with a dual-mode presentation of material rather than a single mode (Moreno and Mayer, 2002; Kalyuga et al., 2000; Tindall-Ford et al., 1997).

Working memory is very important in the therapeutic process. We want clients to remember prior insights, facts, feelings, and thoughts in order to build toward a state of healing and healthier functioning. Interactive Art Therapy takes full advantage of this dual-mode presentation of material in helping clients reach their therapeutic goals.

CONTIGUITY EFFECT

Some have wondered if it matters whether auditory and visual materials are presented separately or together (Tindall-Ford et al., 1997). Mayer and Sims (1994) described a contiguity effect in connection with dual-coding theory. In the simplest terms, they found that auditory and visual material presented simultaneously, the contiguity effect, was the most effective for learning.

This concept was further demonstrated in studies that presented material to students either with words alone or with words and corresponding pictures. The research demonstrated that students remembered significantly more of the information when it was presented in a verbal format along with relevant visual material (Moreno and Mayer, 2002; Kalyuga et al., 2000; Mousavi et al., 1995; Tindall-Ford et al., 1997).

Many therapists use workbook materials and written homework assignments in the therapeutic process. Although these techniques may be effective to a certain extent, the research cited here seems to suggest that the visual material presented in combination with auditory processing might be of greater benefit. In addition, in my experience, it is the exceptional client who will actually follow through and complete written assignments at home without the support and encouragement of having a therapist present.

APPLICATIONS FOR INTERACTIVE ART THERAPY

Interactive Art Therapy certainly reflects a practical application of these research findings in the therapy setting. Being able to process, learn, and remember therapeutic material more effectively means the material is available to build on in session after session. It is also conceivable to suggest that enhancement of the therapeutic process in this way may shorten the course of therapy and lead to longer-lasting positive effects from treatment.

It has been acknowledged for some time that the relationship between therapists and clients in itself is a significant factor in the healing process. Not only does Interactive Art Therapy enhance learning through the dual mode of presenting material, but it also enhances the therapeutic bond between therapists and clients as they collaborate together. This is a special reward for both therapists and clients.

![]()

Chapter 2

Cage of Fears

OBJECTIVE

The Cage of Fears illustration is designed to help clients identify the fears that keep them imprisoned. Once identified, this intervention will begin helping them to discover a way out of the cage so that they might experience a new freedom in making life choices.

RATIONALE

Fears are a powerful force that can keep us imprisoned, unable to pursue dreams, goals, relationships, etc. Many of us don’t want to admit that we have fears so powerful we can’t overcome them without help. Acknowledging fears means exposing personal weaknesses and vulnerabilities. However, exposure is necessary to diagnose the problem accurately and an accurate diagnosis is necessary for effective treatment.

The bars of fear do indeed create a prison and this fact must not be minimized. If minimization occurs, one may escape the cage of iron bars but will do so with chains and shackles that continue to cling. Goals may be reached and tasks accomplished but one will wonder why the load is so heavy and the energy required to move it so great. The joy that should accompany accomplishments melts into sheer exhaustion.

Identifying fears is the first step to diminishing their power. Once the bars of fear are identified, the door can be opened in one of two ways. Doors are kept closed with locks. Typically, the locks are either keyhole locks or combination locks. A key might unlock the door. Keys are equivalent to insight, the “aha” experience, and are more likely to work with individuals who have sufficient ego strength to apply their new understanding. They are not so bound by low self-esteem, self-doubt, and feelings of inadequacy.

Combination locks may also be in place to keep the door closed. Usually, three numbers are required to open a combination lock. The search for these three numbers may require much trial and error. It can be tedious work that takes a long time to complete. Individuals who are kept prisoner by combination locks are often so bound by their fears that efforts to free them are achieved in miniscule steps. In other words, long-term psychotherapy may be necessary.

Each client will have different names on the bars of their Cage of Fears. However, the following examples are common.

• Fear of looking foolish

• Fear of failure

• Fear of loneliness

• Fear of not measuring up

• Fear of being criticized

• Fear of being misunderstood

• Fear of death

• Fear of being found out

• Fear of abandonment

Although we most often think of fears in a negative connotation, it is also possible that fears may be necessary for our protection. For example, a fear of water may be healthy if one who doesn’t know how to swim is considering jumping into a roaring river. Fear of snakes may be healthy if they are poisonous and one doesn’t know how to properly handle them. Similarly, babies placed in playpens with bars may be “imprisoned” for their own safety. Therefore, once fears are identified, we need to determine if they are healthy fears, which serve to protect us from harm, or if they are truly hindering our growth and development.

Once it has been determined that identified fears are a hindrance, clients and therapists can determine a course of action to free the client. Any number of therapeutic techniques may be effective. These include systematic desensitization, assertiveness training, building self-esteem, family therapy, social skills training, etc. It may be helpful for clients who are learning new techniques for managing their fears to go on a “weekend pass” from their Cage of Fears. They will need a chance to try out these new techniques but may not yet have the confidence to follow through consistently. A “weekend pass” gives clients the opportunity to do this and then return to the safety of their cage for evaluation.

It will be important in using the Cage of Fears illustration in therapy that therapists not be perceived as wardens. Wardens are powerful individuals who hold the keys and the combination to the lock. Fears tend to make us vulnerable and dependent. It seems very appealing to have someone stronger take care of us and provide protection. Who wouldn’t like such an easy solution to his or her problems? However, as we know, the easy solution is not always the solution that helps us grow and mature. Therapists who take on the role of warden can inadvertently reinforce the fears and dependency. Clients can easily take on the additional fears of, “What if I don’t please my therapist?” and/or “What if my feeble attempts at being assertive make me look foolish to my therapist?”

Whatever specific therapeutic techniques are used to deal with fears, clients need to be empowered to open the door themselves. Those who hand them the key or give them the combination numbers to the lock also have the power to lock them up again. This reinforces the underlying premise of Interactive Art Therapy. Clients and therapists must do the work together with therapists taking on the role of coach more often than that of director or teacher (or warden).

CAGE OF FEARS EXERCISE INSTRUCTIONS

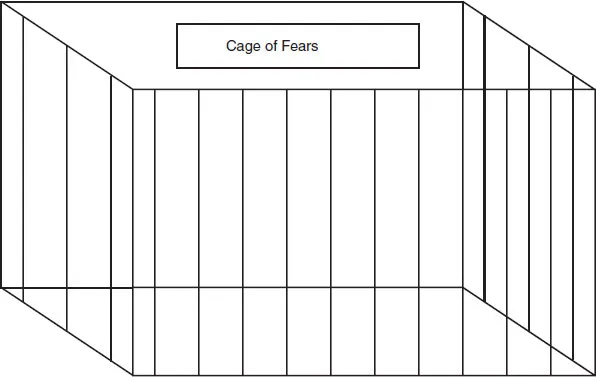

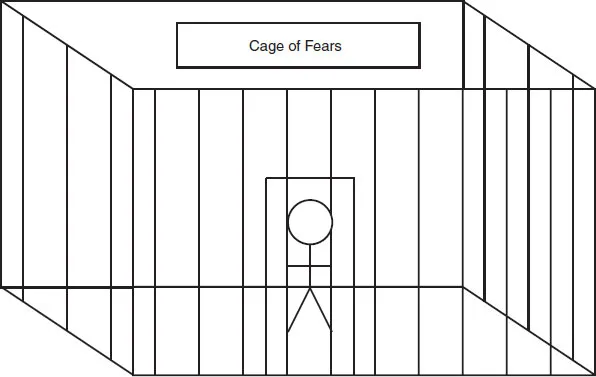

The Cage of Fears is one of the easiest of the Interactive Art Therapy drawings. If you can draw a semistraight line, you’ve got this one mastered. To begin, therapists draw the cage, as illustrated in Figure 2.1. Once the cage is drawn, therapists then draw a stick figure inside the cage, as in Figure 2.2. A door encloses the stick figure.

Now it is time for clients to work. Clients who are trapped in fear will instantly relate to being locked in a cage. It is explained to clients that each bar of the cage represents one of their fears. Clients are then asked to label each bar of the cage with one of their own fears. Ask clients what it feels like to see themselves caged in by fears with the door locked tight. This typically evokes strong emotions, which therapists and clients will need to process together.

FIGURE 2.1. Sample Cage of Fears.

FIGURE 2.2. Cage of Fears with person inside.

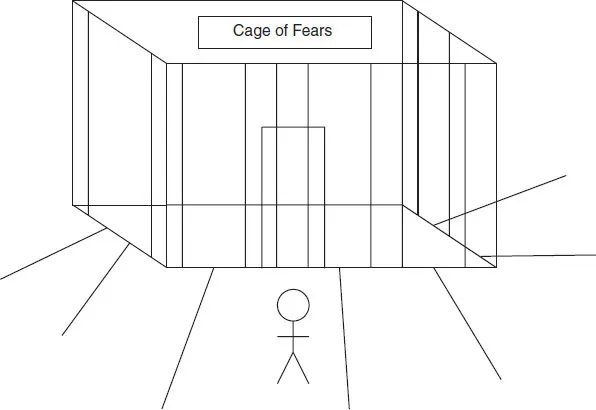

Next, draw a lock on the door and explain symbolically the way of escape, either with a keyhole or a combination lock. Both therapists and clients will recognize if there is an “aha” experience symbolizing use of the key to unlock the door. For most clients, the combination lock more accurately describes their situation. The combination lock illustration may directly guide the development of clients’ treatment plans. Therapists and clients work together to discover the numbers of the combination lock that will unlock the door. The treatment plan will reflect this, with interventions such as journaling, learning social skills, developing assertiveness, systematic desensitization, exploring family-of-origin issues, and others. Some clients will need to confront their fears. Examples might be confronting abusers; establishing boundaries in relationships; or feeling worthy of asking a boss for a raise. As each fear is overcome, clients can imagine that bar of the cage falling over, as in Figure 2.3. Eventually, they will be able to literally see that nothing holds them back from reaching their goals.

FIGURE 2.3. Individual is released.

VIGNETTE

Martha was a forty-year-old woman who came for therapy because her husband of twenty years was having an affair with a younger woman. Martha had two strong-willed teenage children that she was left to manage alone. Understandably, Martha was devastated and came for therapy because of clinical signs of depression. She was having trouble sleeping, didn’t feel li...