- 152 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Dutch Revolt 1559 - 1648

About this book

The Dutch Revolt 1559-1648 begins by illustrating the historical background and causes of the revolt. This is followed by chronological sections devoted to each phase of the revolt and an assesment section that takes a more thematic approach, looking at the military, economic, political and constitutional issues.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Dutch Revolt 1559 - 1648 by P. Limm in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One:

The Background

1

Historical Background

In 1627 the Spanish councillor of state Fernando Giron considered the struggle between the Spanish crown and its rebels in the Low Countries to be ‘the biggest, bloodiest and most implacable of all the wars which have been waged since the beginning of the world’ (28, p. 58). By that date the war had already lasted sixty years and still had another twenty to run. There was continuous fighting from April 1572 to April 1607 (apart from a cease-fire of six months’ duration in 1577) and from April 1621 to June 1647. Yet as one historian has written recently: ‘There can no longer be any doubt that the Spanish crown had come to accept the principle of Dutch political and religious independence by 1606, and that there was never subsequently any Spanish ambition or plan for reconquering the break-away northern Netherlands’ (54, p. xiv). Why, then, did the war continue for as long as it did?

Jonathan Israel thinks the answer is that ‘there were strong contradictory pressures towards war and peace in both the Republic and Spain and these contradictory tendencies derived from political and economic circumstances intimately linked to the major problems of the Republic and Spain’ (54, p. xv). A modern account of the Spanish-Dutch conflict thus has to identify the major issues and problems facing Spain and the Netherlands in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and then to set those issues and problems in their proper context.

Many accounts of the revolt have adopted an unduly narrow nationalistic or religious stance. Only recently has the revolt been set more appropriately in an international context. Geoffrey Parker has shown how the revolt became the focal point for other European struggles and developments, so that especially after 1572 the conflict came to influence the policies of England, France, the German princes and even the Ottoman Sultan. He has suggested that after 1598 revolt developed further into a global conflict: ‘The Dutch Revolt, which began among a few thousand refugees in north-western Europe… spread until it affected the lives of

millions of people and… [became] … so to say, the First World War’ (81, pp. 62–3).

Not surprisingly, such a war raises a number of questions for the student of early modern Europe. Why did the struggle take place? How and why did it develop? What were the calculations and objectives of the contestants and their neighbours? Finally, what were the economic, social, military and political consequences? This book will attempt to answer these questions.

The Habsburgs and the Burgundian inheritance

The heartland of the duchy of Burgundy lay in eastern France around Dijon. When the last of the Capetian dukes of the duchy died without heirs in 1361, it reverted to King John II of France. However, the circumstances of the Hundred Years’ War (1338–1453) between England and France resulted in John’s imprisonment in England: he assigned Burgundy as an apanage to his fourth son, Philip the Bold. There were dangers for John in this situation, and although Philip regarded himself as loyal to France he nevertheless pursued a policy of territorial expansion. Through marriage, family alliances and war Philip managed to acquire Flanders, Artois and also Franche Comté (known as the Free County of Burgundy, which adjoined his duchy). After Philip’s death in 1404 his successors continued to expand Burgundian authority by further matchmaking, diplomacy, and war, so that by 1467, following the acquisition of Holland, Zealand Hainaut, Mechelen (or Malines), Limburg and Luxembourg, the centre of gravity of the duchy moved towards the north-west. Brussels became the new ducal capital.

Nevertheless, the dukes ruled over not so much a state but a miscellaneous collection of counties, duchies, city-states and prince-bishoprics which individually owed them allegiance. What was needed was an administrative framework to centralise ducal authority and to create a sense of unity. Charles the Rash (1467–77) planned to remedy this situation by taking control of the various territories which separated Franche-Comte and the Netherlands and turning the enlarged Burgundy into an independent kingdom. Unity and the achievement of royal status were his aims.

However, the duke’s enemies joined forces to defeat and kill him at the battle of Nancy (1477). The original duchy of Burgundy reverted by feudal law to Louis XI, leaving the provinces of the Netherlands and Franche-Comte to Charles’s widow, Margaret. Louis XI had plans for controlling the entire inheritance and invaded Franche-Comte, Artois, Boulogne and Flanders. This forced Margaret, with the approval of the Netherlands States-General, to declare war and to seek outside help by marrying her daughter, Mary, to the Austrian archduke (and future emperor), Maximilian of Habsburg. Both Margaret and Mary had to promise the cities and provinces of the Netherlands (by way of a ‘Grand Privilege’), that their ‘liberties’, separate customs and laws would be guaranteed. In this way the northern areas of the old duchy of Burgundy were saved from absorption by France. However, the marriage and the ‘Grand Privilege’ weakened ducal control.

By marrying Maximilian, Mary linked the fortunes of Burgundy with those of the house of Habsburg and although this alliance proved sufficient to force Louis XI to renounce his claims to the Netherlands provinces of Burgundy, it did not prevent him retaining control of the old duchy lands around Dijon. Furthermore, although the ‘Habsburg Netherlands’ was officially recognised by France in 1482, Maximilian soon realised that Mary’s ‘Grand Privilege’ and other charters had undermined her father’s attempts to centralise ducal authority and to create effective institutions of government. The traditionally narrow and highly conservative particularism of the states of the Netherlands had been given a boost. This was significant since Habsburg rule was eventually to founder on the rock of local particularism which expressed itself in the cry of ‘defence of liberties’.

‘Defence of liberties’ became a demand for the preservation of traditional ways of doing things which served the interests of the wealthier sections of society: it was also a demand by traditional rulers for a share in government. When the Habsburgs challenged these ‘liberties’ they aroused great resentment among the richer subjects, a resentment bordering on rebellion. When such resistance was fused with a struggle for religious toleration and a greater degree of freedom by those lower down the social pyramid, the Habsburgs faced an acute crisis of government in the Netherlands which eventually led the seven most northern provinces (the ‘United Provinces’) to renounce Spanish sovereignty altogether and to create the Dutch Republic. How did this crisis come about?

The extension of Habsburg power

Mary died in 1482 but not before giving birth to two children, one of whom, Philip (b. 1478), was recognised by Louis as ruler of the Netherlands in the treaty of Arras (also 1482). However, Philip was only a baby, and Maximilian claimed the right to act as regent. Many of the towns resisted this move because they feared Maximilian would erode their ‘liberties’. After a protracted civil war in which he had to use imperial troops against Brugge (Bruges), Maximilian regained popular support and control of Franche Comté and Artois. Yet in 1493 Maximilian left the Netherlands to become Emperor, leaving the fifteen-year-old Duke Philip in control.

Philip maintained Habsburg rule in the Netherlands (1493–1506) by reviving the process of centralising administration and by keeping on terms with the States-General. In 1496 he married Juana of Castile, a Spanish princess. Juana gave birth to a son, Charles of Ghent, but when he inherited the Burgundian inheritance on the death of his father in 1506 he was only six years old. The real ruler was Margaret, widow of the Duke of Savoy (regent 1507–15).

However, when Charles came of age in 1515 and took over the reins of government, there was little opposition. Having spent all his life in the Netherlands he was a popular figure, especially as he followed the advice of the lord of Chièvres and avoided antagonising the regents of the towns. However, in 1516, on the death of his grandfather, Ferdinand, he became King Charles I of Spain and, three years later, was elected Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. Suddenly his Burgundian interests were relegated in his list of priorities and after 1517, when he left for Spain, Margaret governed the Netherlands for him as regent once again (1518–30), to be followed by his own sister, Mary (regent 1531–55).

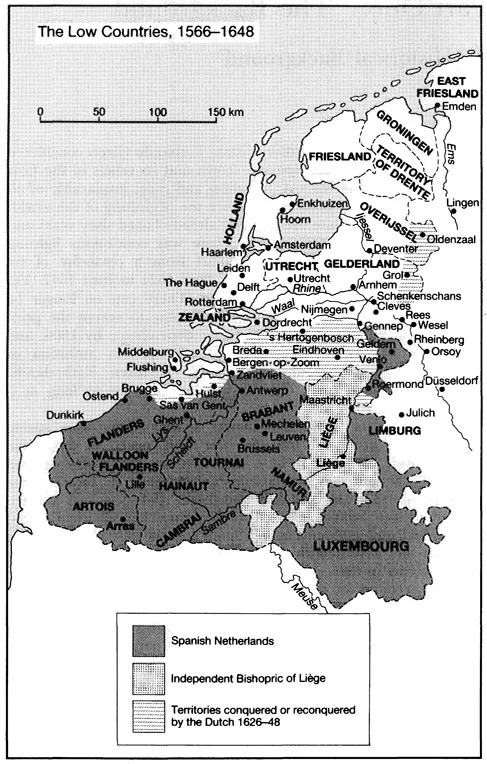

Charles had planned to regain control of the old duchy of Burgundy from France (92) and as a first step towards this end he acquired Tournai in 1521 and Cambrai in 1543, and forced the French to renounce their claims to Flanders. Although Charles ultimately failed to achieve his ambition, he nevertheless revived the expansionist policies of earlier dukes and the process of developing central institutions to unify his government and administration. He extended his authority over the lands of the north-east Netherlands: Friesland was annexed in 1523–4; Utrecht and Overijssel in 1528; Groningen, the Ommelanden and Drenthe in 1536; and Gelderland and Zutphen in 1543. Thus by 1548 Charles controlled seventeen provinces in the Netherlands: Holland, Zealand, Brabant, Flanders, Walloon Flanders, Artois, Luxembourg, Hainaut, Mechelen, Namur, Groningen and Ommelanden (combined), Friesland, Gelderland, Limburg, Tournai, Utrecht, Overijssel and Drenthe (combined). Cambrai remained part of the Holy Roman Empire until 1678 (see map, p. 2).

On 26 June 1548 Charles persuaded the Diet of the Holy Roman Empire (in the ‘Augsburg Transaction’) to allow him to make all his Netherlands territories which formed part of the Empire into a separate administrative unit. Thus provinces ruled by Charles V in the Netherlands became virtually independent of the Empire. In order to guarantee Habsburg control over these territories, Charles persuaded the States of each province to accept a ‘Pragmatic Sanction’ (November 1549), which ensured that following the Emperor’s death, all seventeen provinces would accept the same central institutions and, more importantly, the same ruler: Charles’s son, Philip. There were only a few exceptions. Along with Cambrai, the provinces of Liege and Ravenstein and parts of Gelderland remained entirely free of Habsburg control (19). In Brabant the duke of Aerschot, head of the house of Croy, retained his right to do fealty only to the duke of Brabant. However, while the Pragmatic Sanction provided Charles with the opportunity to consolidate his Netherlands territories and to institution-alise his authority, it did not guarantee unity or unquestioning obedience.

The structure of government

By the mid-sixteenth century, all seventeen provinces of the Netherlands obeyed the orders of the Brussels government and recognised the same ruler. When Charles was absent from the country the provinces recognised his representative as regent. This government consisted of a Council of State for high policy, a Council of Finance for fiscal affairs and a Privy Council for justice. There were law courts (or ‘councils’) in each province and a supreme court, or ‘great council’, at Mechelen. In every province there was a Stadholder appointed by the ruler to ensure that his orders were put into effect (80).

However, the ruler of the Netherlands did not have a single title such as ‘Grand Duke’ or ‘King’. Charles was called ‘Duke of Brabant, Limburg, Luxembourg and Gelderland, Count of Flanders, Artois, Hainaut, Holland, Zealand and Namur, Lord of Friesland and Mechelen’. This emphasised the fact that the Netherlands was a loose confederation of parts. Every province and most of the smaller areas had a representative assembly – the ‘States’ (staten or local parliaments). These usually included delegates from the nobility, the clergy, and the leading towns, though they were not democratically chosen and sometimes one of the three orders might not be represented at all. Yet the States were powerful. They could raise troops and levy and collect taxes and they kept a watching brief on the constitution. They were the main defence of local liberties.

The local States sent delegates to attend the States-General (or general parliament) which negotiated directly with the ruler or regent. Each delegation had to refer back to the local States for advice on any measure and there had to be unanimous agreement before deputies could communicate their decision to the States-General. Furthermore, all the provinces had to approve a measure before it could be enacted. Hence decision-making was a slow process. It was not helped by the fact that the States-General only met every three years, and sometimes there had to be a number of meetings before the necessary unanimity was achieved. Until 1549 only the hereditary provinces of the house of Burgundy were allowed to attend, but after that date this right was extended to all those provinces who had assented to the Augsburg Transaction of 1548. Over some issues a certain amount of cooperation between representatives could be achieved, though it would be wrong to exaggerate this. Often, as we shall see, States used ‘defence of liberties’ to mask inter-province rivalry, even rivalry between cities within a province. Thus, although under Charles Netherlanders began to speak of their patrie or Fatherland, many states retained a selfishness which seriously undermined the development of corporate status (95).

The Habsburgs, and the Burgundians before them, had always seen the value of securing the loyalty of the high nobility and had granted a number of aristocratic families special privileges such as high-ranking positions in the church, local government and the army. The most eminent of them were elected to the prestigious Order of the Golden Fleece and were consulted on both domestic and foreign affairs in the Council of State. Under Mary, when the Council of State was rarely convoked, government was often conducted by way of a series of informal consultations with selected members. Charles V followed the advice of his secretary Nicholas Perrenot, lord of Granvelle (father of the more famous cardinal), who stated in a memorandum to his master in 1531:

‘It seems that it would be good that, of the great nobles whom it shall please the emperor to appoint to the said Council of State, two or three should always reside continuously near the… queen to assist her. They should be persons most suitable for her service… That when matters of importance arise, all the knights of the Order [of the Golden Fleece] should be summoned’.

However, Philip II’s policies were to undermine the consultative role of the high nobility and reduce its share of government. As will be seen later, the nobles reacted strongly to this threat. Their rebellion served to encourage the centrifugal force of particularism and to act as a catalyst for a number of other divisive influences.

Other divisive influences

The map of the Netherlands (p. 2) shows that Charles V’s provinces covered a large area (34,000 square miles), but that there were many physical obstacles impeding communications between them. The provinces of Holland, Zealand, Utrecht and Friesland were practically surrounded by the sea and cut off from the ‘heartland provinces’ of Hainaut, Artois, Flanders and Brabant, by numerous rivers, dykes, and lakes. The eastern and north-eastern provinces of Limburg, Luxembourg, Gelderland, Overijssel, Drenthe and Groningen were cut off from the rest by dunes, bogs and heaths and by the independent principality of Liège. Owen Feltham, an English traveller in the Netherlands in 1652, described the area as being ‘The great Bog of Europe … it is the buttock of the World, full of veines and bloud, but no bones in’t’ [doc. 1].

This quagmire often made horse-and-cart transport impossible. The usual route from Friesland to the south was by boat, but this form of transport was not very quick. Only twenty-five miles separated Breda from’s Hertogenbosch but it still took about eight hours to go from one to the other. In the south communications were better, and letters from Antwerp could reach Ghent or Brussels in a day. In terms of time-distance, as Parker has pointed out, ‘Brussels and Antwerp were… closer to Paris and Cologne than they were to Amsterdam and Groningen’ (80, p. 22). More significantly for later events, the postal courier took between two and three weeks to reach Spain. Small wonder, then, that there were strong local institutions and traditions in the Netherlands and little sense of unity between the provinces.

There were different legal and fiscal systems and different linguistic areas. There were about 700 different legal codes in the Netherlands, and it was quite possible to avoid punishment by crossing into a different province. Even within a province codes could vary from town to town (the province of Artois had 248 separate legal codes). Yet Netherlanders were prepared to live with the illogicality of this system because they valued the existence of guaran...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Maps

- A note on currency

- Acknowledgements

- Seminar Studies in History: Introduction

- Part One The Background

- Part Two Descriptive Analysis

- Part Three Assessment

- Part Four Documents

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index