![]()

Chapter 1

Brain Growth and Organization

The two minds [the cerebral hemispheres] can cooperate with each other in a deep, synergistic relationship that fosters creativity and maturity, or they can sabotage each other, leading to a plethora of psychological and psychosomatic problems.

Fredrick Schiffer, MD

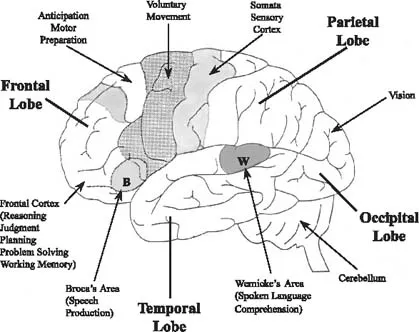

Since the brain looks rather unassuming—just three pounds of grayish matter covered with convoluted ridges and valleys—it is hard to imagine that it contains so many intricately developed parts. If you made a cut through the brain, you would see a mix of gray matter, containing densely packed cell bodies 1.5 millimeters thick, and white matter, comprised of axons (see the appendix to this chapter for a definition of neurons and their component parts). Gray matter forms both the outside, called the cortex, and the discrete structures on the inside. As with any body organ, each brain structure performs distinct functions. For instance, separate areas of the cortex are dedicated to processing visual stimuli, understanding language, speaking, planning, etc. (see Figure 1.1). However, the precise boundaries are different for each of us and change over time because of environmental influences.

The brain is made up of systems or functional modules. Although it has been over fifty years since neurosurgeons initially mapped out the sensory-motor cortex, the recent discovery of functional imaging techniques, which capture the brain in action, has revived interest in the systems perspective of brain functioning. Scientists now understand that most tasks require brain activity involving several areas of the brain and that collaboration between these areas is critical to healthy brain functioning.

FIGURE 1.1. Functional Areas. Contemporary mapping of the mind is based on two types of studies: those using functional imaging techniques that visually record neural activity as an individual is performing a mental and/or behavioral task, and those that show the effects of damage to particular areas of the brain and the effects of stimulating specific brain regions. The brain is a complex, interactive, and dynamic system. Remarkably, functional areas can change— given the right circumstances—and one area can take over the work of another.

To produce any response, even the blink of an eye, groups of neurons must work together. As the brain develops, neurons from every part of the brain form assemblies or circuits. Local assemblies then feed into larger and larger groups until they are organized into elaborate networks, subsystems, and finally, systems. This functional linking of groups of neurons into networks and into separate systems allows us to engage in several activities at the same time for example, thinking, driving, drinking a glass of water, and listening to music, and also experiencing various emotions such as anger, fear, and joy.

When the brain is operating efficiently, multiple assemblies of neurons are firing in unison, and information is flowing freely from one area to another. We are not born that way, however. We develop the capacity to coordinate various functional areas of the brain, such as our cognitive and emotional systems, which are located in separate areas of the brain, in childhood. In fact, neuroscience teaches that our early interpersonal experiences play a critical role in determining how well we make use of our genetic potential to integrate all these brain functions.

We begin this chapter by looking at how the brain grows. We then focus on how the brain organizes both from a vertical and horizontal perspective, explaining just how the various brain systems collaborate. As the brain develops, what it ends up looking like on the “inside” directly reflects what we have experienced on the “outside.” In other words, our early relationships and experiences directly influence the ultimate architecture of the brain. In particular, securely attached children are likely to have brains that are not only biochemically more balanced, but also structurally better organized than children who grow up in chaotic or abusive environments.

HOW THE BRAIN GROWS

Mental functioning is directly related to the number of both neurons and synapses (connections between neurons) in the brain. Whereas the proliferation of new connections increases the potential for learning, new patterns of connectivity between neurons, which are strengthened and stabilized through use, result from actual learning. The density of synapses reaches its peak about the age of three and it remains at this level until age ten, according to Peter Huttenlocher (1994) of the University of Chicago. Generally by age sixteen, the number of synapses has dropped to adult levels. Because a child's brain is rapidly making new synapses, it is much more malleable than an adult's. Increased plasticity, or potential for change, has both advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, adverse environments affect children much more acutely than adults; therefore, abuse or neglect in early childhood can result in long-term impairments. On the other hand, since children's brains are still in the process of being organized, they possess a remarkable ability to rebound from severe brain injuries. This scientific insight led to a new lease on life for preschooler Matthew Simpson (Swerdlow, 1995).

Matthew Simpson

At four, Matthew began experiencing epileptic-like seizures that neither drugs nor any other standard treatment could stop. As the interval between seizures grew shorter and shorter, doctors were concerned that he might die from a neurological disorder called Rasmussen's encephalitis, a rare form of intractable seizures that spreads only through one hemisphere and results in progressive paralysis on one side of the body, inflammation of the brain, and mental deterioration.

Lacking any other options, Matthew's parents agreed to let Benjamin Carson, a pediatric neurosurgeon at Johns Hopkins, perform a hemispherectomy—a procedure that involves removing the entire left side of the brain. Over time, cerebrospinal fluid usually settles in the areas once occupied by critical brain structures. However, there are risks to this surgery, and doctors typically recommend it only as a last resort. Only 58 such operations were performed on children at Johns Hopkins from 1968 to 1996 (Carson, 2003).

Normally, each side of the body works in tandem with the opposite hemisphere of the brain. Thus, a sound heard by the right ear is processed in the left auditory cortex. Besides controlling the movement on the right side of the body, the left brain is also critical for problemsolving and language skills.

Remarkably, the right side of Matthew's brain soon took over the functions typically performed by the left side. Within eighteen months of the surgery, Matthew showed hardly any signs of impairment in cognitive or motor functioning—except for limited use of his right arm. He performed well in school, even excelling in mathematics. If an adult were to undergo this radical procedure, transfer of functions from one side of the brain to the other would not be possible. Fortunately, Matthew Simpson was still at an age when his brain could create and reassign the neural connections needed to return him to normal functioning.

Early Growth

The human nervous system begins its development about two weeks after conception, when cells on the surface of the embryo begin to form a neural plate. Soon this neural plate thickens, and vesicles (pouches filled with cerebral spinal fluid) form at the front end of the neural tube. The formation of neurons, which evolve from precursor cells surrounding the vesicles, is complete well before birth.1 Once produced, neurons migrate, or move to their approximate final location. By the time the fetus is twenty weeks, most neurons are already in place. Shortly after birth, neurons finish migrating, but they continue to differentiate until they start performing their specific functions (Shepard, 1994).

During the prenatal period, maternal alcohol, drug, and tobacco use, malnutrition, and other adverse experiences can have a detrimental effect on the developing brain. These prenatal insults often result in prematurity, low birth weight, or poor interactive capacities (Aitken and Trevarthen, 1997). With any toxic substance, the amount ingested and age of the fetus—the earlier, the worse the outcome—often determine the extent of the damage. For example, FAS, which is caused by heavy drinking during pregnancy, results in mental retardation along with physical deformities including a small head, thin upper lip, flattened jawbone, and poorly developed ridges between the nose and mouth.

Maternal stress also can affect fetal brain development. Martha Weinstock of Hadassah Medical School in Jerusalem, has stressed pregnant rats by exposing them to a loud buzzer. She found that the pups of the stressed mothers, when compared with controls, were more fearful and irritable, and produced more stress hormones. Apparently, their brains were less able to regulate the stress response (Weinstock, Fride, and Hertzberg, 1988; Fride and Weinstock, 1988; Weinstock, 1997). Similar research at the University of Wisconsin found that monkeys whose mothers were stressed during pregnancy had enhanced hormonal response to stressful events later in life (Clarke et al., 1994). When compared to a control group, they also appeared less interested in playing and more aggressive toward their cage mates. Further studies of other prenatally stressed monkeys suggest that stress in utero results in a wide range of impairments including neuromotor difficulties, diminished cognitive abilities, and attention problems. Symptoms were more severe when stress occurred early in pregnancy (Clarke and Schneider, 1997; Schneider et al., 1998). Researchers hypothesize that a mother's stress hormones can damage the developing brain of the fetus. Very recent research shows that maternal stress hormones released during pregnancy may adversely affect human fetal brain development (Glynn, Wadhwa, and Sandman, 2000) .

At birth, all essential brain structures are present, but brain development is far from complete. During the first two years, our brains go into “fast forward,” producing numerous, cyclical growth spurts. All told, in the first year of life, the brain expands two-and-a-half times—growing from 400 to 1,000 grams (Schore, 1994). By four years of age, the cortical utilization of glucose, the brain's source of energy, is twice that of an adult. This high rate of glucose metabolism, which reflects the explosion of synapses, continues until around age ten (Chugani, 1998). Myelinization, or a formation of a sheath of glial cells around the axon, is another step in the development of the nervous system. This process, which begins late in gestation and continues on into adulthood, facilitates the communication between neurons. Brain pathways myelinate at different times and at different rates. For example, whereas the ascending tracts, which stretch from the brain stem to the cortex, begin myelinating before birth, the descending tracts, which run down from the cortex to the lower brain centers, do not begin to myelinate until late infancy. Perhaps we are not wise until old age because some descending tracts, which allow us to think before we react, may not completely myelinate until the sixth decade of life (Benes, 1994).

Brain structures do not all mature at the same time. For instance, the sensory and motor areas of the cortex develop before the association areas, which respond to and integrate different types of sensory stimuli. Thus, after the primary auditory cortex takes in the specific features of a sound and the secondary areas integrate its various aspects, the association areas link it to other sensory information. One of the main association areas, Wernicke's area, is located just above the temporal lobe and is responsible for processing language. Association areas allow us to perform complex symbolic activities such as reading, writing, and mathematics, which require the integration of auditory, visual, and spatial information. If these areas develop too slowly, a child can suffer from both learning disabilities and limitations in higher-order language skills (Lyon, 1996).

The prefrontal cortex matures last. Fibers from all cortical and lower brain systems converge, ensuring communication not only between all areas of the brain but also between the brain and the visceral systems. Delayed growth here can result in a wide range of problems involvin attention, inhibition of impulsive responses, planning, reasoning, judgment, self-monitoring, and the lack of creative and thoughtful responses (Lyon, 1996). Research suggests that although the prefrontal areas begin to develop as early as the latter part of the first year of life, these areas continue to mature through adulthood.

Although brain growth explodes between birth and two, growth spurts occur at other ages as well. Typically, each overproduction of neural connections is followed by the selective elimination of unused connections—a process known as pruning. This cycle of “boom and bust,” in turn, results in brain reorganization or “remodeling” (Huttenlocher, 1994). This “use it or lose it” style of development allows the brain to adapt its responses to the specific needs of the environment. In addition, there is another process, an “experience-dependent” (versus an experience-expectant process), which involves the formation of neural connections in response to unique experiences (Greenough, Black, and Wallace, 1987). In this way, experience eventually determines the final architecture (i.e., circuitry) of the brain. As mentioned in the introduction, the relationship between infant and caregiver is instrumental in fostering and stabilizing these new neural connections.

Some periods of “remodeling” are referred to as critical periods because certain experiences are needed at these times in order for brain development to proceed normally. Otherwise, brain development can be derailed. As the classic studies of Hubel and Wiesel (1979) have shown, kittens can lose their sight if they are deprived of appropriate visual stimuli. When researchers covered the kittens' eyes for a few weeks, neurons associated with vision degenerated, and pathways within the visual cortex deteriorated. Similarly, if a congenital cataract blocking visual stimuli is not removed in infancy, vision in that eye will be lost forever.

Just as various subcortical and cortical regions develop at different times and at different rates, the right and left hemispheres alternate periods of rapid growth. Research suggests that a sequential growth spurt in one hemisphere is first followed by bilateral growth, and then by rapid growth in the other hemisphere (Thatcher, 1994). Between three and four years of age, a major reorganization occurs right after the brain has gone through just such a developm...