![]()

Part I

AN OVERVIEW OF OLDER ADULTS’ USE OF THE WEB: GOVERNMENT AND PRACTICAL CONCERNS

![]()

Chapter 1

The Use of New Information Technologies in an Aging Population

Terrie Wetle*

Deputy Director, National Institute on Aging

By 2030, there will be 70 million older Americans, twice as many as there are today. The oldest of the baby boom generation is now entering its 50s, and the first 65th birthday among this group, in 2011, is fast approaching. As they have since birth, the boomers will be responsible for another major population shift in the United States, the rapidly accelerating rise in the number and proportion of people age 65 years and older. Today, and in the near future, more people than ever before are coming face to face with diseases, disability, and a variety of complex health issues associated with growing older. They are also interested in seeking ways to live longer, healthier lives.

The effort to understand healthy aging and to develop new treatments for both illness and chronic conditions has intensified with the aging of the population. In recent years, funding for basic biomedical, clinical, and social research has increased steadily. Society is fixed on managing acute and long-term health care costs. Individuals are seeking ways to keep aging and age-related disease from taking a toll on personal health.

Communicating an expanding new knowledge base is a critical part of developing and adopting strategies for an aging population. Such information is vital, not just to policymakers and health professionals, but is increasingly important to aging adults and their families as pressure in-

creases to undertake more self-care and preventive interventions. With these forces in mind, the National Institute on Aging (NIA) supports a variety of projects that examine how older people relate to and use new information technologies, and how technology can be improved and used to help maintain and improve health as the U.S. population and the world population grow older.

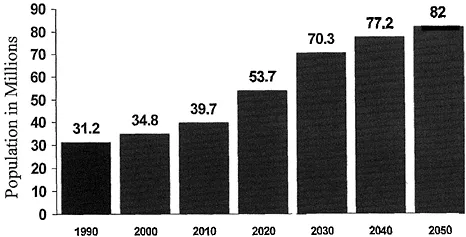

The importance of the health and well-being of current and future generations of older people cannot be overstated. The number of persons aged 65 and older has been growing for quite some time, and the proportion of the population they represent has grown from about 4% in 1900 to 13% today. See Fig. 1.1.

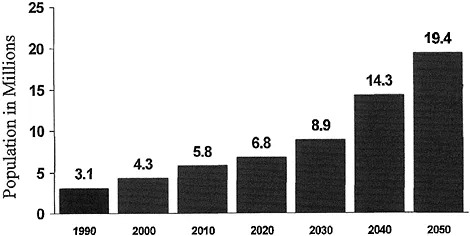

Moreover, the proportion of people at the advanced age of 85 and older—those most at risk for disease and disability—currently is rising faster than the elderly population as a whole. There are 4 million people aged 85 and older in the United States, and by 2030, that number is expected to double (NCHS, 1999, p. 22). By 2050, it is projected that the number of people aged 85 and older could soar to at least 19 million, and might even be as high as 27 million or more. See Fig. 1.2.

Because the prevalence of chronic conditions and disability increases with advancing age, these population changes increasingly challenge health and social service systems (NCHS, 1999, p. 46). About 25% of people 70 and older could not perform at least one of nine physical activities, according to one survey, and people aged 85 and older were 2.6 times more likely to be unable to perform the same tasks. Among people 70 and older living in the community, 34% received help or supervision with some aspect of daily life. Eventually, the severity of disability affects an individual’s independence, out-

stripping the ability of an older person or of the general community to assist. Today, 4% of people 65 and older are in nursing homes. Here, too, the data show significantly increased risk with age—11 of 1,000 people age 65–74 were in nursing homes, compared with 46 of 1,000 between ages 75–84 and 192 of 1,000 age 85 and older (NCHS, 1999, p. 26).

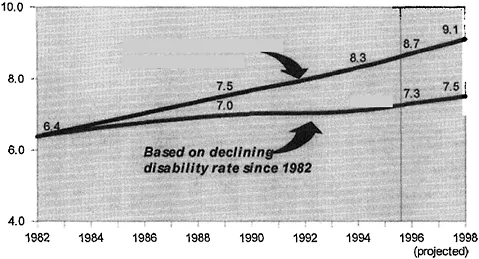

While both younger and middle-aged persons contemplate their own futures, fear of disability and dependence in later years are powerful motivators for seeking information about strategies to maintain good health and to prevent disease. Similarly, older persons have a strong interest in maintaining good health and in seeking good information about health concerns. Efforts to improve health, particularly among older persons, have had some success. An important recent study suggests that disability in old age need not be inevitable. Scientists at Duke University and at RAND found that, since the 1980s, rates of disability among older people have declined. Looking at several waves of the National Long-Term Care Survey, the Duke study found that the proportion of disabled people 65 and older fell in relative terms by 14.5% between 1982 and 1994 (Fig. 1.3, Manton, Corder, & Stallard, 1997). There were an estimated 7.1 million disabled older people in 1994, about 1.2 million fewer than would have been expected if disability rates had remained the same as they were in the baseline year of 1982. Declining disability rates were observed for both men and women, and occurred even for persons at very advanced ages. Data from several countries indicate similar reductions in rates of disability among older persons.

The research community is now attempting to identify the specific factors contributing to this reported drop in the rate of disability. The message

from the disability decline is clear: The functional status of aging populations can be improved over time. The goal now is to maintain, and even to accelerate, these declines in the rates of disability by preventing and intervening against disease and disability associated with later life. Scientific research has, and will continue, to develop effective strategies and methods for preventing disease and disability.

As research continues to pinpoint what matters most for well-being in old age, current knowledge and scientific advances need to be communicated to health professionals and to the public if they are to make a difference. Of course, how health professionals and individuals choose to use the findings from medical research depends on a number of factors, including national policies on health care financing and on the structure of the health care system, which are not addressed here. Regardless of policy, individuals should have timely access to accurate information to assist them in making their own decisions regarding health behaviors and medical care.

Providing this information offers both opportunities and challenges as society ages, and as technologies for disseminating and receiving information change. To start, it is important to note that the audience is a receptive one. Despite falling rates of disability, millions of older people will nonetheless face disability or chronic disease as sheer numbers of older persons increase. This group—people with chronic conditions or disability—is most likely to seek out and act on health news and information, according to health communications research (Roper/Starch survey, 1997). Primary causes of disability among older people are osteoporosis and fractures, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, arthritis, vision and hearing loss, and cognitive impairment. Important areas for communicating relevant health information relate to diet, exercise, preventative health care and screening, early diagnosis and treatment of disease, reduction of excess disability, and use and misuse of alcohol, tobacco, and medications. Older people are also receptive to information about how to deal with physicians specifically, and with the health care system more generally.

The need to understand and more actively manage one’s own health is certainly driven by the increasing risk of disease and disability with age, but other factors are also likely at play. The rapidly changing health care system is proving difficult to negotiate for each of us, not just for older people. Changes in the structure and financing of health care are putting increased pressure on individuals as the health care system struggles with balancing efficiency and costs with delivery of appropriate care to a rapidly aging population. For example, some 15% of Medicare beneficiaries are now enrolled in managed care whereas there was no managed care option just a few years ago. These pressures may require that the elderly and their families more closely monitor their own health, find out more about their health care providers, and gather more data to inform personal health decisions.

In this environment, the traditional model of the doctor-patient relationship, at least as far as information is concerned, also may become obsolete. Instead of the doctor as the primary source of health information for his or her patients, the relationship is likely to become much more interactive. Figure 1.4 provides a model of information flow in the last century. In the new millennium (Fig. 1.5), patients are becoming health care “consumers,” armed with the scientific information and data available from many sources, in addition to the experiential information they always received from family and friends.

How will people access the information they need to address aging, health, and their changing relationships with the health care system? For older people, the Internet is of increasing interest, but it is unlikely to wholly replace traditional sources. Currently, older Americans as a group still look mostly to television and newspapers for information and entertainment. They watch more television than any other age group, viewing at a particularly high rate during the day for news and talk shows on both broadcast and cable media outlets. They are the largest group of regular subscribers to newspapers as well; about 69% of people over age 65 read a daily newspaper.

Increasingly, however, adu...