Plato’s Cave

Plato’s cave is one of philosophy’s most memorable and haunting images. I have already said a little about it in the introduction, but we can now start to explore it in more detail. In the Republic, Plato asks us to imagine prisoners ‘living in a cavernous cell down under the ground’ with a fire behind them. The prisoners, who have been there since childhood, are bound so they cannot turn their heads and can only see the shadows on the wall before them. These shadows are cast by artefacts, statuettes of people and models of animals being carried by unseen figures behind them, moving up and down in front of the fire. The prisoners think that the shadows are the only things there are to see, the only reality there is. If they are released from their bonds and forced to turn around to see the fire and the statues, they become bewildered and disoriented, and are much happier left in their original state. Only a few can bear to realise that what they see are only shadows cast by the artefacts, and these courageous few begin their journey of liberation that leads past the fire and right out of the cave. Here, outside the cave, they find not merely artefacts but the real things, the objects of the real world. Moreover, should they return to the cave and tell of what they have seen, they will be viewed with great suspicion by those who remain, and no one will listen to or understand what they have to say (see Plato 1993, 514a–517a).

What makes the cave image so compelling is its suggestion that we might be like these prisoners, that everything we ordinarily take to be reality might, in fact, be no more than a shadow, a mere appearance, and that the real world might be something quite different. In our ordinary experience, of course, we are perfectly familiar with the apparent as well as the real and can usually tell the difference between them. The stick in water appears to be bent, but we can readily establish that it is really straight, and that the bent appearance was an illusion. But if absolutely everything that we encountered, everything in our ordinary experience, was merely an appearance, an illusion, and quite different from what was really the case, we would have no idea that we were being systematically deluded in this way. We would imagine that we had genuine access to reality, that what we saw was all that there was to see. And if anyone were able to pierce through this veil of appearances and to grasp the true nature of reality, they would view those left behind as no more than prisoners confined to a world of illusion. To them, everything that those left behind took to be solid reality would seem to be no more than shadows.

There are a number of ways in which the cave story can be interpreted. First of all, it can be read very broadly as ‘an invitation to think, rather than to rely on the way things appear to us’ (Blackburn 1994, 253). In other words, it is an invitation to engage in philosophical reflection. To start thinking philosophically about our beliefs, we have to abandon our unthinking confidence that what we ordinarily take to be knowledge, really is knowledge. We have to become critical of received opinion and common-sense beliefs, beliefs that are presented to us as self-evident or unquestionable. Second, the cave story illustrates Plato’s own particular philosophical views about the nature of knowledge. Philosophers have always been interested in giving an account of knowledge—of the nature, scope and limits of what we can know—an area of philosophical reflection that has come to be known as epistemology. The cave serves as a concrete representation of Plato’s own epistemological position. It is a representation of his view that all that our senses reveal to us are mere shadows, mere appearances removed from reality. For Plato we are just like the prisoners in the cave to the extent that we think the world we ordinarily encounter through our five senses is the real one. In order to comprehend the world as it really is, we have to escape from this prison; we have to go beyond what is given to us in experience. And in addition to serving as an illustration, the cave may also be seen as a thought experiment designed to question our ordinary reliance on the senses. In a setup of systematic deception like that of the cave, our senses would not be able to see through that deception and so cannot be relied upon (see Jarvie 1987, 48).

The cave image is also significant because it brings us to our first encounter between philosophy and the cinema. As I mentioned in the Introduction, it has often been noted that there are uncanny similarities between the cave Plato imagines and the modern cinema. As in Plato’s ‘picture show’, so, too, in the cinema we sit in darkness, transfixed by mere images that are removed from reality. The very structure of the cinema parallels that of the cave. The cinema audience watches images projected onto a screen in front of them. These images are projected from a piece of film being moved past a light behind them. And the images on this piece of film are themselves merely copies of the real things outside the cinema. There are some striking parallels here. Indeed, if anything, the cinema improves on the cave as a place of illusion. What are being projected on the cinema screen are not mere shadows, but sophisticated, highly realistic moving images. The history of the cinema is itself one of increasingly sophisticated representations of reality, with the progressive addition of sound and colour making the illusion more and more complete. Moreover, through seamless editing, films usually do not call attention to the fact that they are merely representations of reality up on the screen and not reality itself—the so-called ‘reality effect’.

There is a sense, then, in which, as Ian Jarvie puts it, we recreate Plato’s thought experiment every time we step into a cinema (see Jarvie 1987, 48). And it is always possible to think of the cinema itself in cave-like terms, as a refuge from reality, a place where we can go in order to escape from the outside world, to lose ourselves in deception, illusion and fantasy. However, it is important to note that despite the clear similarities between the cinema and Plato’s cave, there are also some significant differences. In particular, the kind of deception involved in Plato’s account is much more profound than anything we might find in the cinema. If the cinematic image is a mere representation, an illusion, it is an illusion that we voluntarily subject ourselves to, that we allow ourselves to be taken in by, and in full awareness of its status as an illusion. That we are not seriously taken in by the cinematic image reflects the fact mentioned earlier: ordinarily we can distinguish perfectly well between illusion and reality, between the apparent and the real. We can do this even if the illusions are relatively sophisticated, like those we find in the cinema. In addition, leaving the cinema and returning to the ‘real world’ all takes place within our ordinary experience, just as the distinctions we make between appearance and reality are ordinarily made within the realm of our ordinary experience. For Plato, in contrast, it is ordinary experience as a whole that is illusory. In order to escape from illusion and to comprehend reality, we have to escape entirely from the realm of ordinary experience.

Plato’s account does not only have to do with knowledge, but also with a certain kind of liberation bound up with knowledge. Ignorance for Plato is not bliss, but rather a form of enslavement. We are prisoners in so far as we are prevented from grasping the true order of things because of the limits of everyday experience, of our common-sense understanding of the world. To gain knowledge is to escape from the imprisonment of our ordinary conception of the world. There is also a suggestion in Plato’s account that ignorance can enslave us in a more concrete sense as well. Plato portrays the prisoners as mistaking for reality the shadows of effigies that are being carried by others. The implication is that we can be effectively enslaved or controlled by other people when we take for reality the images they feed to us, when we believe what they want us to believe. Only if we become critical, if we come to see these false images for what they are, will we be in a position to free ourselves from this kind of enslavement.

Seen in these terms, Plato’s story of the cave, of imprisonment and its overcoming, starts to acquire wider resonances. It calls to mind first of all what is involved in the process of an individual’s growing up, of leaving childhood behind and becoming an adult. This is more than just a process of physical development. An important part of growing up is intellectual growth, in which we come to question the ideas and beliefs, along with the moral principles and standards, that have been fed to us by our parents, teachers, and others over the years. When we are young we uncritically accept whatever we are told about the world. As a result, we are very much influenced and determined in our thinking by the views, opinions and attitudes of those around us. As we grow up, however, we often find that many things we have hitherto accepted without question are, in fact, questionable—and may even be false. In so doing, we start to become critical, to examine our existing beliefs and standards, to sift through them and weigh them up. Such critical thinking is an important part of breaking away from dependence on others and of establishing our own identity, our own views on the world, and our intellectual and personal independence.

Second, the cave story calls to mind forms of imprisonment and their overcoming in a wider social context. An important way in which people can be controlled or manipulated is by filling their heads with misleading or false images of the world. And this is a far more effective form of social control than straightforward coercion, because here we are willingly doing what other people want us to do. Consider, for example, the advertising images manufacturers bombard us with, designed to make us think that their products are indispensable to our well-being or happiness. Or consider the role of political propaganda in fostering certain views of the world, or orchestrating public opinion in various ways, in order to help bring about the political goals of others. Movies, too, have sometimes been seen as part of this, as instruments of cultural or political indoctrination, encouraging people to mistake a false cinematic reality for the reality of life in the world. In this view, which can be found in some of the older-style Marxist theorising about film, for example, unsuspecting audiences are in danger of being brainwashed by films whose apparently realistic content is determined by the dominant social ideology (Wilson 1986: 12–13; Stam 2000: 138–139). So in this wider social and political context, as well, it would seem that we can become like Plato’s prisoners, controlled by others because we take the images they present us with for reality.

However, unless we assume that people are no more than passive, unthinking dupes, completely at the mercy of socially produced images, we are not condemned to such imprisonment. We can still differentiate between illusion and reality. What the possibility of such deception means, once again, is that it is important to be critical. Becoming critical of these images imposed on us, seeing them for what they are, and grasping the truth of our circumstances is an important part of breaking away from this kind of subjection, of ‘growing up’ and attaining some degree of independence in our lives. The cinema also need not be seen as merely echoing dominant forms of thinking or prevailing attitudes, doing no more than reproducing and perpetuating them. Film is capable of critically interrogating ways of thinking and views of the world, of illuminating, challenging and subverting them (see Stam 2000, 138–139). Amongst other ways, it can do this by making use of images of intellectual and social imprisonment like Plato’s cave.

These, then, are some of the wider socio-political implications of the cave image, and they are often alluded to in cinematic portrayals that make use of the cave. This brings us back to Bertolucci’s The Conformist. As Julia Annas notes, Bertolucci uses Plato’s cave image quite deliberately and explicitly in the film to comment on the imprisoning delusions of fascism. It does not appear in the Alberto Moravia novel on which the film was based (see Annas 1981, 257–258). The cave is already alluded to early on, when Clerici visits the fascist ministry in Rome and comes across functionaries walking through the corridors carrying statues of people (a bust) and animals (an eagle). Now in Paris, Clerici, having closed the shutters and turned his old philosophy professor’s office into a gloomy cave-like place, recalls how the professor used to lecture on Plato’s cave and how much of an impression this made on him. In response, the professor compares the deluded prisoners in the cave with the inhabitants of Fascist Italy, blinded by propaganda. Since Clerici is himself one of those who has been trapped and blinded, one of the cave dwellers, he is unaware of the irony of his own recollections. But Bertolucci underscores the professor’s point, because there is enough light entering the room to cast shadows on the wall behind them. At one point in Clerici’s exposition, as he is emphasising a point, his shadow is caught appearing to make a Fascist salute; and at the end, after the professor expresses doubts that Clerici is, at heart, really a Fascist, he opens the shutters and Clerici’s shadow disappears in the resulting light. In this way, Bertolucci uses the cave image to emphasise both the shadow world of Fascist beliefs and Clerici’s ultimately uneasy relationship with it. Raymond Boisvert suggests that the special enmity Clerici seems to have towards his philosophy professor is not merely the hostility of the cave dweller towards those who have succeeded in escaping the cave. His enmity arises above all because it was the professor who gave him the training in critical thought that makes it impossible for him to do what he most wants to do, which is to fit in with the Fascist order, to conform (see Boisvert 1984, 52).

In The Conformist, the cave has been used in order to comment on forms of confinement in a wider social and political context. In Cinema Paradiso (Guiseppe Tornatore, 1989), the cave image figures in a tale that is primarily about an individual’s journey out of childhood and intellectual confinement. As Erich Freiberger (1996) argues, Cinema Paradiso makes use of the cave image, and, indeed, the parallel between the cave and the cinema, to portray the development of its main character Toto towards adulthood and intellectual independence. In the film, Toto (played as an adult by Jacques Perrin) tells the story of his childhood in a small Sicilian village and, in particular, his childhood friendship with the projectionist Alfredo (Philippe Noiret) at the local cinema. On Freiberger’s reading, the local cinema can be seen as a cave-like place in which the villagers are spellbound and seduced—in effect, ‘bound’—by the conventional opinions and standards of behaviour that they see projected onto the screen. But Toto has already begun to escape from this cultural confinement because he has turned away from the screen and has come to know the projectionist ‘behind the scenes’. The liberating escape from the cave that Plato envisages is paralleled in the film’s overall story, which traces how Toto gradually comes to escape from the narrow confines of small village life and heads off into the wider world to gain an education.

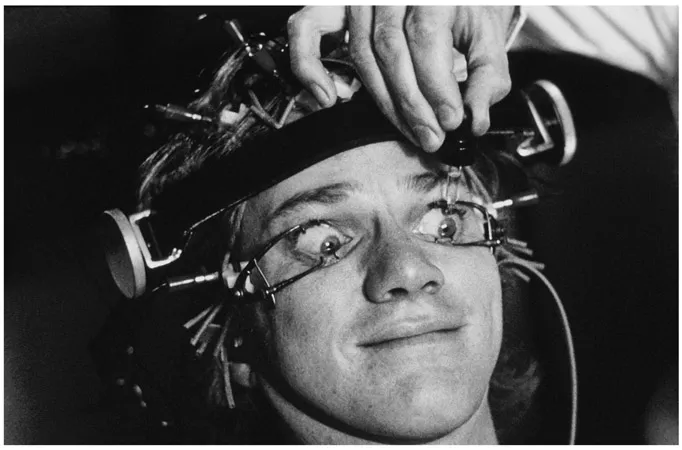

Figure 1.2 Alex at the movies (A Clockwork Orange, Stanley Kubrick, 1971. Credit: Warner Bros. Courtesy of the Kobal Collection).

Before moving on, there is one more portrayal of Plato’s cave worth noting. One of the most interesting cinematic appearances of the cave, once again in the form of a cinema, can be found in Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange (1971). Here, the enslaving force is psychological conditioning in the service of the state and social order. As a condition for his release from prison, the film’s vicious anti-hero Alex (Malcolm McDowell) is subjected to a kind of cinematic aversion therapy (Figure 1.2). In this cinema, he is strapped to his seat, unable to turn his head away from the screen. Clips on his eyelids mean that he is unable even to close his eyes. Behind him, shadowy, white-coated scientists sit with banks of instruments, orchestrating the proceedings. He is shown a string of violent film images, and with the help of nausea-inducing drugs is gradually conditioned to feel sick at the very thought of violence. The result is a model citizen, of sorts. This scenario strongly recalls Plato’s cave because Alex is literally bound to his seat, unable to look away from the cinematic images; and through subjection to these images, his independence is destroyed and his behaviour controlled. However, Kubrick’s film also introduces a number of perverse twists that set it apart from other cinematic representations of the cave. In this cave story, going into the cave actually brings about liberation at one level, in that Alex has to enter the cave, to submit to the conditioning, in order to gain his freedom from prison. Of course, he has now become a prisoner in a more profound sense, and to that extent Kubrick gets us to sympathise with Alex; but at the same time it is not at all clear that it would be a good thing for this particular prisoner to escape from his cave.