- 161 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Visuo-spatial Working Memory

About this book

Representation of the visual and spatial properties of our environment is a pivotal requirement of everyday cognition. We can mentally represent the visual form of objects. We can extract information from several of the senses as to the location of objects in relation to ourselves and to other objects nearby. For some of those objects we can reach out and manipulate them. We can also imagine ourselves manipulating objects in advance of doing so, or even when it would be impossible to do so physically. The problem posed to science is how these cognitive operations are accomplished, and proffered accounts lie in two essentially parallel research endeavours, working memory and imagery. Working memory is thought to pervade everyday cognition, to provide on-line processing and temporary storage, and to update, moment to moment, our representation of the current state of our environment and our interactions with that environment.

There is now a strong case for the claims of working memory in the area of phonological and articulatory functions, all of which appear to contribute to everyday activities such as counting, arithmetic, vocabulary acquisition, and some aspects of reading and language comprehension. The claims for visual and spatial working memory functions are less convincing. Most notable has been the assumption that visual and spatial working memory are intimately involved in the generation, retention and manipulations of visual images. There has until recently been little hard evidence to justify that assumption, and the research on visual and spatial working memory has focused on a relatively restricted range of imagery tasks and phenomena.

In a more or less independent development, the literature on visual imagery has now amassed a voluminous corpus of data and theory about a wide range of imagery phenomena. Despite this, few books on imagery refer to the concept of working memory in any detail, or specify the nature of the working memory system that might be involved in mental imagery.

This essay follows a line of reconciliation and positive critiquing in exploring the possible overlap between mental imagery and working memory. Theoretical development in the book draws on data from both cognitive psychology and cognitive neuropsychology. The aim is to stimulate debate, to address directly a number of assumptions that hitherto have been implicit, and to assess the contribution of the concept of working memory to our understanding of these intriguing core aspects of human cognition.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Temporary Memory

FINDING YOUR WAY IN THE DARK

Suppose you were to close your eyes for a moment and attempt to describe the scene in front of you. If the scene is familiar, this may be a fairly trivial task. If the scene is new to you, the task is still possible, but it is less easy to fill in details that you may have forgotten from your most recent memory of the scene. Perhaps a more difficult task might be to ask you to navigate your way blindfold through a room that is cluttered with furniture and of which you have had only the briefest of glimpses a few moments before.

For most people these tasks would appear to involve some form of visual memory of the scene or room. What kind of memory system might be involved? Retention of the information is required over periods of seconds or minutes, thus we can discount any form of memory system such as iconic memory that is purported to retain information only for much shorter periods (e.g. Kikuchi, 1987; Purdy & Olmstead, 1984; Sperling, 1960). Similarly, the information is unlikely all to be held in some form of longer-term memory, although details about the nature of the objects in the scene could be retrieved from a long-term knowledge base. Moreover, retention of the particular form, colour, and location in the scene would more likely rely on a temporary memory trace. Also it seems reasonable to assume that much of the information in the temporary memory trace will be in a form that represents the visual and spatial properties of the scene, or at least in a form that would allow these properties to be reconstructed. It is possible to use verbal labels such as “there is a bed on the left”, but it is unlikely that you would have done this for all of the items in the room on the basis of a brief single viewing.

There is no doubt that most of us could perform this kind of task with some individual variability in performance. We could also carry out many other tasks that require temporary storage of visual and/or spatial information. This in turn suggests that we have some form of memory system for storing the necessary information. However, this conclusion begs a number of questions. If such a memory system is available, is it specialised for dealing with visual and/or spatial material, or could a general purpose temporary storage system suffice? If it is a specialised system, can it deal with visual and spatial information, or is the system fractionated further into two systems, one for visual and one for spatial information? Why would there be a need for a specialised system of this kind and what are the everyday tasks in which it would be involved? What determines its capacity limitations, and what sort of time limit can be described as temporary?

Much of the discussion in this book will centre around these questions, and will be based on three assertions. The first of these assertions is that the system comprises a memory function that provides storage, in some form, of visual and/or spatial information on a temporary basis. This memory system is separate from some form of more permanent memory, but information flows between the permanent and the temporary systems in the absence of sensory input. This assertion is possibly the best supported empirically, and is possibly the least controversial.

The second assertion is somewhat less widely accepted, and claims that visual and spatial working memory are best thought of as separate cognitive functions. In this conception, visual working memory is passive and contains information about static visual patterns. The system is closely linked with, but is distinct from visual perception. Elsewhere, this cognitive function has been referred to as the “inner eye” (Reisberg & Logie, 1993) or as part of the visuo-spatial scratch pad (Baddeley, 1986; Logie, 1986, 1989). A similar cognitive function has been attributed to a cognitive structure referred to as the “visual buffer” (Kosslyn, 1980). As I shall argue later, Kosslyn’s visual buffer is a rather different concept, and the visuo-spatial scratch pad is seen as one system rather than two. Also, on reflection, the term “inner eye” has the trappings of an homunculus and begs questions about inner screens and the possibility of an infinite series of inner eyes watching inner screens. For these reasons, I shall adopt the term “visual cache”, to distinguish the system from its predecessors and from its theoretical doppelgängers. In this two-component model, spatial working memory retains dynamic information about movement and movement sequences, and is linked with the control of physical actions. Here, as elsewhere (Reisberg & Logie, 1993), I shall refer to this system as the “inner scribe”. The scribe provides a means of “redrawing” the contents of the visual cache, offering a service of visual and spatial rehearsal, manipulation, and transformation.

The third assertion also flirts with polemics by maintaining that information from sensory input does not access the visual cache and the inner scribe directly but only via some form of long-term memory representation. I shall argue that this last feature is not just characteristic of the visual cache and the inner scribe, but is true generally of all of working memory. This contrasts with the traditional view that information from sensory input has to pass through working memory in transit to long-term storage. In the course of the book it should become clear that this cannot be the case, and that sensory input accesses long-term memory representations first. These representations are activated, and ipso facto the activated representations become available to working memory which holds the information momentarily and implements on-line processing. The information may then return to long-term memory, thereby strengthening the originating, activated trace. Alternatively, processing in working memory may generate novel information which then allows novel traces and novel associations to be stored on a more enduring basis.

In making these assertions explicit, I do not intend them to be accepted without discussion or debate, but rather to act as a focus for such debate. The intention is to investigate whether these assertions are tenable, and thereby to illuminate visuo-spatial short-term memory function, and its place within the bailiwick of working memory.

A BRIEF GUIDE

In the remainder of this chapter the investigation will proceed with a discussion of the case for a short-term memory system. In Chapter 2, I shall discuss the literature on visual imagery as a form of mental representation, and Chapter 3 will examine the range of tasks in which a visuo-spatial working memory system might be involved. Chapter 4 gives a detailed account of the working memory model on which many of the ideas in this book are based, and argues the case for separate visual and spatial elements of that model. Chapter 5 considers the range of evidence for visual and spatial working memory from patients with various forms of brain damage. The final chapter moves towards a coherent account of the evidence presented, considers ways in which the visual imagery literature and the working memory literature might have a common interest, and adds a few theoretical speculations of my own.

There is of course one important assumption underlying the rationale for this kind of book; that is whether there is indeed a strong case for any form of memory function that deals with information solely on a temporary basis. This topic could fill a volume on its own, and is discussed in some detail in contemporary textbooks (e.g. Baddeley, 1990; Eysenck & Keane, 1990). However it is worth considering briefly in the remainder of this chapter before going on to ask whether there is a visuo-spatial temporary memory system.

IS THERE A TEMPORARY STORAGE FUNCTION?

Drawing from our intuition, the ability to retain information over a short period of time seems fundamental to a wide range of tasks in everyday life. In order to know what we are going to do next we need to remember what we have just done. While counting, we have to remember how far we have gone through the counting sequence in order to know which number comes next. In reading, we have to remember what we have just read in order to make sense of what we are now reading; and we have to retain an unfamiliar telephone number just long enough to press the buttons in the right sequence. The cognitive abilities and systems that allow us to perform these tasks have a different role, and are of a different nature from memory functions that allow us to access our store of general knowledge of the world or to retrieve information about past experiences and life events. This distinction was recognised by the British philosopher John Locke as long ago as 1690.

The next faculty of mind … is that which I call retention … This is done in two ways.

First by keeping the idea which is brought into it, for some time actually in view, which is called contemplation.

The other way of retention is, the power to revive again in our minds those ideas which, after imprinting have disappeared, or have been as it were laid aside out of sight … This is memory which is as it were the storehouse of our ideas. (Locke, 1690, Book II, Chapter X, paragraphs 1–2)

There has been considerable effort directed towards understanding how human temporary storage of information is achieved. The prevailing view during the 1950s was that memory was a single system, that there was no distinction between temporary storage and longer-term storage, and that the same system was involved in retaining a telephone number and recalling lengthy sequences of prose learned at school. In addition the prevailing experimental techniques of the time involved presentation and retrieval of lists of verbal material rather than aspects of everyday cognition.

In 1965 an influential paper by Waugh and Norman revived an idea similar to the Locke distinction, which had been proposed by William James in 1890. Their suggestion was of two memory systems: a primary memory, responsible for short-term storage and a secondary memory responsible for longer-term storage. Information in primary memory was thought to be displaced by new material unless it was maintained by rehearsal. Information could be copied from primary memory to secondary memory by means of rehearsal.

Recency and Short-term Memory

One of the major sources of evidence for a distinction between primary and secondary memory came from experiments involving short-term retention of word lists. In this sort of experiment subjects are presented with a list of items, and are then asked to recall as many of the items as they can in any order (known as free recall). What tends to happen in this situation is that people start by recalling the last few items in the list, and this they can do very well. Next they will recall the first few list items, and performance here is again reasonably good. Finally they will attempt to recall as many items as they can from the middle positions in the list. The tendency to recall accurately items from the end of the list is known as the recency effect because these are the most recently presented items in the list. The tendency to do reasonably well at the beginning of the list is known as the primacy effect. The overall pattern is referred to as the serial position curve (Glanzer & Cunitz, 1966; First reported by Nipher, 1876).

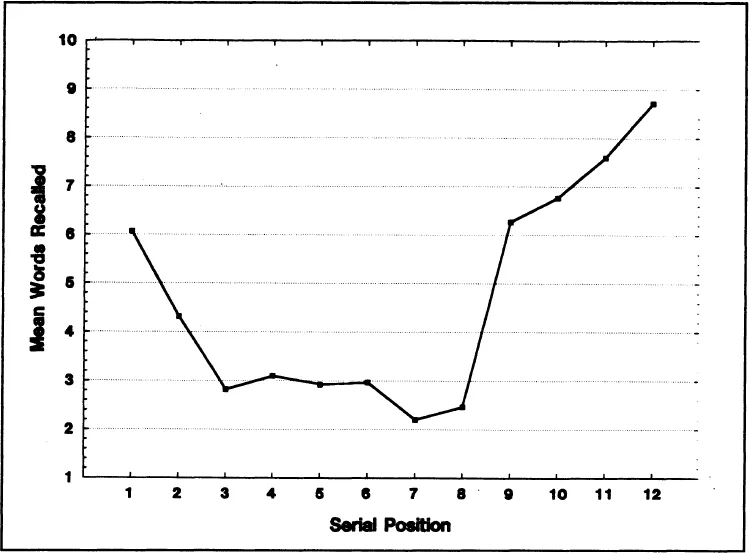

Figure 1.1 shows the serial position curve derived from free recall by a sample of 30 subjects, of 10 lists of 12 bisyllabic words (Capitani, Della Sala, Logie, & Spinnler, 1992). This is the pattern when recall occurs immediately after the list has been presented. However if there is a filled delay of even a few seconds (during which the subject performs a simple, unrelated task) before recall is required, then the primacy effect is retained but the recency effect disappears. After a delay the last few list items are remembered no better than items from the middle of the list.

The effect of a delay on recency but not primacy was taken by a number of authors to suggest that primacy reflected a long-term or secondary memory system while recency reflected the operation of a short-term or primary memory system. It was thought that items early in the list would be rehearsed and would therefore enter long-term memory. Rehearsal would be more difficult as the number of items in the list increased, and therefore transfer to long-term memory would be much less efficient. Items near the end of the list would still be in a short-term store immediately after list presentation, but would be displaced by other material after a delay. There are a large number of papers on this topic, but a typical study is reported by Glanzer and Cunitz (1966). Although initially these data seemed to provide very strong evidence for a distinction between two memory systems, subsequent work has indicated that the recency effect may not after all uniquely reflect the operation of a short-term store (for reviews see Capitani et al, 1992; Greene, 1986).

FIG. 1.1. Serial position curve derived from free recall by a sample of 30 normal subjects, of 10 lists of 12 bisyllabic words (Capitani, Della Sala, Logie, & Spinnler, 1992).

One difficulty with the short-term memory interpretation of recency arose from the report by Baddeley and Hitch (1977) that free recall of the details of rugby matches taking place over a period of several months showed the familiar serial position curve, with events early in the sporting season showing a primacy effect, and events taking place over the few weeks prior to memory test showing a recency effect. It is clear that recency spread over several weeks could not reflect the operation of a short-term memory system. A second difficulty was reported by Watkins and Peynircioglu (1983), where subjects were given lists of 45 items, but with the items from three different categories (riddles, objects, and sounds). When recall was tested subjects showed three separate recency effects for each of the three categories of items even although they had been presented mixed in a single list. These findings suggested that recency was a phenomenon of long-term storage as well as a phenomenon of immediate free recall.

Neuropsychology also contributed to the demise of recency as a phenomenon specifically of short-term memory. A number of demented patients have been reported who had severely impaired verbal memory span1 (a standard test of short-term memory capacity), but appeared to show normal recency (Spinnler & Della Sala, 1988; Wilson, Bacon, Fox, & Kaszniak, 1983). In normal adults (Martin, 1978) and in patient populations (Della Sala, Pasetti, & Sempio, 1987) that show normal recency and span there are very poor correlations between span and measures of recency. Hitch and Halliday (1983) have shown that recency and memory span appear to develop at different rates in young children, further supporting the idea of a dissociation between these two phenomena. In addition, memory span is invariably impaired by concurrent articulation of an irrelevant word, a technique referred to as articulatory suppression (e.g. Baddeley, Thomson, & Buchanan, 1975; Levy, 1971; Murray, 1968). However, recency is unaffected by concurrent articulation (Richardson & Baddeley, 1975).

Further evidence that undermined the link between recency and short-term memory arose from the use of the continuous distractor paradigm. This involves interspersing the presentation of each item with some distractor activity throughout the list (Bjork & Whitten, 1974; Tzeng, 1973). The last item is also followed by this distractor activity, but under these conditions both primacy and recency appear very clearly, whereas if the distracter appears only after the last item and not throughout the list, the usual disruption of recency appears. This adds to the doubt as to whether recency genuinely reflects the functioning of a short-term memory system.

There are currently two alternative explanations for the recency effect: one that it reflects a retrieval strategy (Baddeley & Hitch, 1977; Baddeley, 1986), and the other that it reflects temporal discrimination of memory traces (e.g. Crowder, 1976; Glenberg et al., 1980). Crowder describes this last interpretation in terms of watching telephone poles receding into the distance. Those that are close can be discriminated easily, and those that are more distant merge together and are more difficult to discriminate from one another. So too with memory traces receding in time. Those traces that are recent are more readily discriminated than those more distant in time.

These explanations are not necessarily mutually exclusive, in that a sensible retrieval strategy would be to recall those items that are most readily discriminable, rather than, say, recalling items in their original order of presentation. This provides an arguable case for recency being a general phenomenon of memory, applying both to short-term and to long-term memory. Thus the recency effect is still considered by many authors to be associated with a short-term memory function, although not uniquely so.

A more recent view of verbal short-term memory is that it comprises more than one component, specifically a passive, phonological store and an articulatory rehearsal process (see later discussion and Chapter 4). According to this approach, measures of memory span may reflect the operation of one component of verbal short-term memory (articulatory rehearsal), while recency reflects the other component of short-term memory (the phonological store). This view would account for the lack of association between these two measures of short-term memory performance (Vallar & Papagno, 1986). Because articulatory suppression is thought to disrupt articulatory rehearsal, this account would also cope with the resistance of recency to this form of suppression. However recency is not only resistant to the effects of articulatory suppression, it is also resistant to techniques that are thought (Salamé & Baddeley, 1982; 1989) to disrupt the contents of the phonological store, such as irrelevant speech played to the subjects throughout presentation of the word lists for recall (Logie, Trivelli, & Della Sala, 1993).

This essay is not the most appropriate venue for a detailed discussion of recency in verbal short-term storage, and...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- 1. Temporary Memory

- 2. Mental Representation

- 3. The Visual and The Spatial

- 4. Working Memory

- 5. Neuropsychology

- 6. Assumptions, Reconciliation, and Theory Development

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Visuo-spatial Working Memory by Robert H. Logie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.