![]()

Part One

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES

![]()

1

The Complexity of Inclusive Aid

Rachel Hinton and Leslie Groves

Inclusive aid

We will spare no effort to free our fellow men, women and children from the abject and dehumanizing conditions of extreme poverty, to which more than a billion of them are subjected (United Nations Millennium Declaration, September 2000).

The arrival of the 21st century heralded a new sense of optimism. At all levels people came together in a concerted effort to address world poverty. Advocates from 189 countries signed up to the United Nations Millennium Declaration, ready to fight for the rights of poor people. This declaration commits countries to fight world poverty and its main thrust was the setting of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), including halving the numbers of people living in extreme poverty by 2015. Poverty reduction has thus become the overarching goal of international development with a call for the adoption of more pragmatic and people-centred policy that takes on board the local knowledge and priorities of the poor.

Despite the expertise and energies of so many, the MDGs are unlikely to be attained within the agreed time frame. Far greater trust, accountability and responsibility must be developed within and among all actors, at all levels, as a condition for success. This requires a new focus on the socio-political dynamics of aid and an understanding of development as a complex system. Until this shift occurs, poverty elimination through aid programmes will remain elusive.

This book begins with a conceptual and historical analysis of aid to set the context for the proceeding chapters. The analysis reveals the major challenges and opportunities facing the aid community today. In Part Two, Chapters 4 to 10 look at the issues of power, procedures and relationships from a complex systems perspective. Each chapter represents a different voice in the development system: the donor; the government; the international non-governmental organization (INGO); and the Southern activist. Each author shows how entrenched procedures work to preserve and, indeed, are sometimes used to justify the status quo. These examples contrast with cases of recent procedural innovations in Africa and Asia that embrace significant cultural and political influences. The case studies illustrate how achieving inclusive aid requires new understandings and ways of thinking about the complexity and dynamics of the entire development system.

Part Three explores ways forward for aid agencies in changing their political, institutional and personal ways of working in order to better meet their commitment to the MDGs. Chapters 11 to 15 examine how organizations can build more-equal relationships with partner countries and create an environment conducive to personal change. They also look at how development practitioners can adapt existing participatory approaches to facilitate the involvement of poor people in holding governments to account for the decisions that affect their lives and for ensuring that governments deliver on their commitments. As a consequence of the systemic approach, the authors argue for greater sensitivity to local and global dynamics. They demonstrate that inclusive aid requires practitioners to re-evaluate and understand the extent to which the changing political context affects the outcome of the development agenda. This necessarily demands scrutiny of different lines of accountability. Crucially, the authors show how translating rhetoric into practice relies on changing the attitudes and behaviours of individual actors, and on the role of personal agency in creating change.

The new dynamics of development

Recent years have seen fundamental changes in dominant aid paradigms. The failure of development policy and practice to raise the standard of living of a large proportion of the world’s poor has prompted a radical rethink of development policy and practice. There has been a dramatic shift from a belief in the importance of projects and service delivery to a language of rights and governance. Among policy-makers there has been an evolving sense of the need to involve members of civil society in upholding their rights and working to promote transparent, accountable government.

At the micro level, this has led to an increasingly sophisticated understanding of the benefits of local participation, and the development of approaches that prioritize the perspectives of poor people. Participatory rural appraisal (PRA) and related methods of participatory learning and action (PLA) revolutionized the way of thinking of many development practitioners, and enabled many primary stakeholders to have a voice in decisions about how project funds were utilized. The World Bank subsequently introduced participatory poverty assessments (PPAs), in part with the hope that they would enable poor and marginalized people to influence policy (Norton et al, 2001). At a macro level, there has been a shift from service delivery to supporting citizens’ entitlement to services. Donors are emphasizing the need to work in partnership with national government rather than create parallel structures for service provision.1 The 1990s witnessed a gradual increase in the flow of aid delivered through governments, as support for democratic national processes grew. The World Bank’s poverty reduction strategy (PRS) process attempts to provide a direct link between grassroots assessment and development of strategies at policy level. It requires the participation of civil society and a move from government-owned to country-owned processes.2 In this new environment policies take a central place whereas projects, from being central to the development process, become one element in a wider development agenda.

These shifts require new approaches and procedures that stress partnership and transparency. But embedded traditions, vested interests and bureaucratic inertia mean that old behaviours and organizational cultures persist. Hence the gap between rhetoric and practice remains wide. The contributions show that the way forward is to seek greater consistency between personal behaviour, institutional norms and the new development agenda. This will require a shift from linear planning for predetermined outcomes to understanding change from a complex systems perspective.

Development actors and the complex aid

environment

For international development to move beyond the new and ambitious rhetoric of aid to a reality where the well-being of poor people is truly prioritized, there needs to be a far clearer understanding of the uncertainty, complexity and dynamics of the entire aid system.3 International development practice is currently based on a linear outcome-oriented perspective, which focuses on individual institutions within the system to a degree that excludes attention to the relationships among actors. Thus, many development efforts fail to recognize the significance of cultural and political influences, and the potential of well-placed individual agency and leadership to effect systemic change.

This section argues that the way forward is to adopt a complex systems approach to understanding the aid system, and its outcomes.4 This requires stepping back from the intricacies of individual projects or programmes and gaining an understanding of the relationships that link the various actors. It necessitates thinking beyond Newtonian modes of analysis (Uphoff, 1992). A central insight from complexity analysis is that the interplay between rules and agents lead to emergent outcomes that are not simply predictable from understanding the individual actors alone. We suggest that adopting a complex systems approach involves two elements. On the one hand, it is essential to understand the choices being made by individual actors and their position and power within the system. On the other hand, it is equally important to understand the wider context – the relationships and networks between actors in the system as a whole – recognizing that the system has its own emergent dynamism and internal logic.

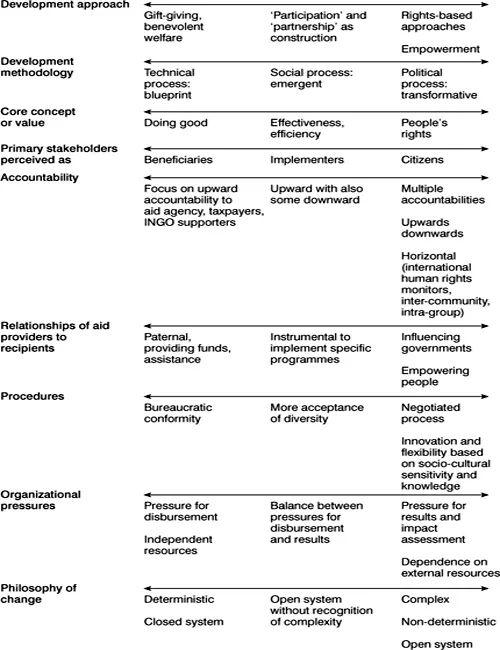

The emergence of certain behaviours are the complex products of interdependent choices made by actors under dynamic conditions. Key actors include non-governmental organizations (NGOs), bilateral donors, international finance institutions, national governments, regional and local governments and ‘poor people’ who are the ‘client group’ of poverty reduction initiatives.Figure 1.1 highlights the extent to which actors in the aid system may be positioned differently. The choices being made and the behaviours displayed will shift at different times and in different contexts. For example, organizations may prioritize contrasting philosophical approaches and procedures at various moments in history. Building relationships with certain actors in the system may be emphasized at the expense of others, often in line with the perceived balance of power. Different significance may be given to different methodologies, values and accountability issues. Shifting organizational and resource pressures will also influence the choices being made. The diagram highlights the importance of recognizing the implications of where individuals and their organizations are situated on the spectrum; as well as of where various actors would assume other organizations to be located with regard to each dimension. The spectrum approach reveals the dangers of classifying organizations into one fixed category. It also points to the problem of programme operations that are based on predicted outcomes planned with only partial knowledge of the system and without constant review and reflection. Such generalizations hide the fluid and interdependent nature of organizations over time and space and the consequence of this is poor programming and policy design, based on inaccurate understandings of the behavioural dynamics of the system.

Figure 1.1 provides a simplified illustration of some of the choices that characterize the different aid actors.

We argue that if the new development agenda is to succeed, then new behavioural traits and capacities need to be prioritized. In the past, organizations have emphasized bureaucratic conformity, upward accountability and meeting financial disbursement targets. We suggest that these behaviours are inappropriate to the needs of the new environment, which requires greater emphasis on flexible, innovative procedures, multiple lines of accountability and the development of skills for relationship-building, such as language and cultural understanding. Internally, new organizational norms based on learning, growth and mutual respect would encourage teamwork and innovation. Leaders would need to provide a sense of clarity of the organization’s mission and values and guide and inspire the team to meet their objectives while remaining reflexive.

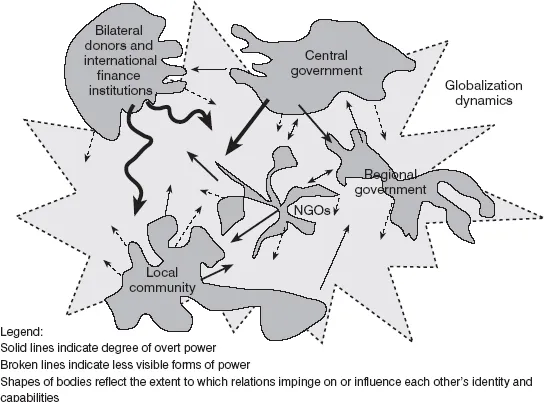

Having explored the behavioural characteristics and choices taken by the development players, it is also essential to understand the interdependence and power dynamics of the different actors and how these in turn influence the choices being made. The schematic diagram in Figure 1.2 attempts to provide an example of such networks and power dynamics. Presenting power and relationships as an entire system reveals the extent to which development is complex and dynamic. Conventional flow charts generally present organizations as boxed entities, an oversimplification of the fact that organizations are at least as complex as the individuals that constitute them. A complex systems diagram illustrates the diversity of relationships as well as their fluidity and interdependence. It is also important to note that with each interaction, relationships evolve and all parties to the relationship are changed.

Figure 1.1 Critical and dynamic choices for aid actors5

Source: developed by Beth Cross, University of Edinburgh7

Figure 1.2 A complex systems illustration of power and relationships8

The diagram takes us beyond common assumptions of power as simple, discreet and unidirectional. The arrows illustrate different degrees of power, which can be exerted through different means, can be two-way or one-way, and can be overt as well as covert. The backdrop to all of these relationships is the global political system, which plays a key role in determining the development agenda and its effectiveness in reducing poverty. In Figure 1.2, each organization is represented as an organic, fluid shape. Contours are determined by the relationships that actors have with other actors. The relationships are neither static nor predictable. Certain actors in particular organizations may have closer relationships with certain actors in other organizations (where the shapes move out towards each other), whereas others may not prioritize relationship-building with those outside their organization (where the shapes are introverted).

Building effective relationships is key to understanding and addressing power relations and developing mutual respect and communication, all essential to ensuring effective aid practice that is sustainable in the long term. It is important for organizations to provide incentives for staff to develop inter-organizational links, recognising how these impact on the professional choices being made. This is no easy task and great efforts are required to develop relationships of trust, even between ‘like-minded’ bilateral organizations who have many behavioural features in common.6 It is clear that even greater attention will need to be given to ensure cooperation between organizations from different parts of the system. Through taking a complex systems view, the multiple relationships become apparent. Rather than being between two actors (either donor–NGO or donor–recipient government), as has traditionally been the focus, other significant actors are placed clearly in view – most significantly, the primary stakeholder.

In summary, this section has explored behavioural patterns to highlight the extent to which individual actors and organizations prioritize and adopt different behaviour types and choices. This reveals the complexity of a system, where generalizations are dangerous and where understanding difference is key. Building effective and ethical relationships is central to breaking down power imbalances, opening up communication channels and developing trust between actors. We suggest that these elements are fundamental to developing an aid system that recognizes complexity and which evolves accordingly into a system that will be more effective in reducing poverty.

Transforming procedures: a focus on cultural

and political dynamics

Transformations in the procedures employed by donors have not kept pace with the rapid changes in development thinking. In Chapter 2, Caroline Robb reflects on Cornwall’s (2000) work on the new language of aid and development, encompassing such terms as empowerment, ownership, partnership and participation. Organizational cultures from an era when the reductionist thinking dominated development have proven ill suited to the demands of dynamic people-centred development. This is despite increasing evidence that attention to local (citizen) analysis often reveals a more complex understanding of why a programme has succeeded or failed and can heighten progress towards reaching development goals. Yet, the persistence of old habits in the new development context has pernicious effects. Existing structures continue to reduce the effectiveness of interventions.

In Chapter 8, Charles Owusu provides an innovative example from ActionAid, which has sought to radically transform its planning and reporting procedure...