- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Russia's Wars of Emergence 1460-1730

About this book

Russia's emergence as a Great Power in the eighteenth century is usually attributed to Peter I's radical programme of 'Westernising' reforms. But the Russian military did not simply copy European armies. Adapting the tactics of its neighbours on both sides, Russia created a powerful strategy of its own, integrating steppe defence with European concerns. In Russia's Wars of Emergence, Carol Belkin Stevens examines the social and political factors underpinning Muscovite military history, the eventual success of the Russian Empire and the sacrifices made for power.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Russia's Wars of Emergence 1460-1730 by Carol Stevens in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Eastern European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1450–1598

Chapter 1

The constituents of Muscovite power, c. 1450

Prelude

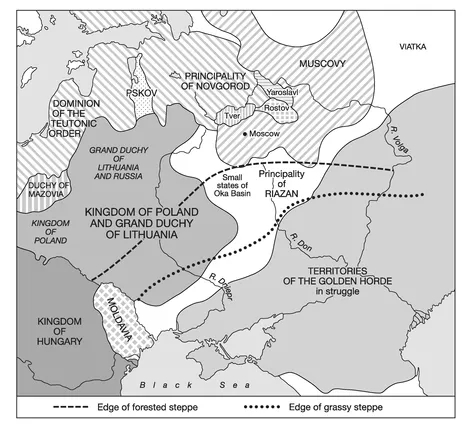

In the first half of the fifteenth century Muscovy was still a principality of quite modest size by comparison with some of its Eurasian neighbours. The territory it claimed enveloped the principalities of Rostov, Tver, and Iaroslavl in a huge westward-facing C, without yet absorbing them. At its widest, in the south, Moscow’s easternmost and westernmost territories were separated by about 800 kilometres (500 miles). In the east its greatest extent from north to south was perhaps a bit larger. These territories in the north-central section of European Russia shared some harsh environmental realities that would play an important role in shaping and limiting Muscovite capabilities in the early modern period (fifteenth–eighteenth centuries). In the north, Muscovy was covered by cold expanses of evergreen forest, taiga, where fur hunting and other forest extraction provided a more reliable living than agriculture alone. Further south, most of the major cities and most of the population was in a mixed forest zone. Here, despite the northern climate and short growing season, agricultural lands were passable and, in one area near the city of Vladimir, even excellent. The forests also served as a protective barrier against the open steppe whose rich lands, trade routes and raiding nomads Muscovy regarded with ambivalence.

The population of Muscovy was sparse and widely dispersed in the first part of the fifteenth century. Even in the southernmost regions, it probably had not yet attained seven people per square kilometre.1 Peasants lived in isolated villages, raising rye and oats, gathering forest products and raising livestock. Small and distant villages simply moved to a new location when soil and other local resources gave out. For those closer to the Muscovite capital, a growing and somewhat denser population encouraged different agricultural techniques in more permanent settlements. In addition to agriculture and extraction, Muscovites also lived from trade, largely but not exclusively in furs, salt, artisanal and forest goods; trade routes led southward across the open steppe to Crimea and to southeastern Europe. In the early fifteenth century the landscape was dominated by those who taxed these fundamental economic activities: Orthodox Christian monasteries and elite landholders who claimed payments from peasants (who could move away if demands became too onerous); trade fairs and transit taxes supported towns and principalities. The Muscovite prince was the ideological and political centre of the system: an overlord who had absorbed nearby principalities and claimed the fealty of those within them.

The lands of northwestern Eurasia in this era had very limited economic, bureaucratic and demographic resources. As a result, military power was not a matter of competitive margins in technology or strategy. A prince’s ability to exercise political authority, despite geographic and institutional limitations, was a key element; although basic, this was not easily achieved. In particular, it depended upon social stability and cohesion from a loyal political elite.

The basic economic and political arrangements of Muscovy had suffered two significant shocks shortly before 1450. First, there was the international demographic catastrophe of the Black Death. In the 1350s and in repeated waves into the 1400s epidemic disease devastated Muscovy’s population and that of its neighbours. Particularly important among these, the Golden Horde was Muscovy’s overlord, guardian of the steppe trade routes, and heir to the western end of the Mongol Empire. Combined with political infighting and economic disruption, demographic shock helped to undermine the Horde’s stability. Early in the fifteenth century the Horde divided into three or four entities, and its control and protection over the steppe trade routes dissolved. Second, between 1430 and 1450, Muscovy erupted into civil war. From 1380 until the start of these hostilities, Muscovy had been on a bumpy but surprisingly successful path of expansion. It had claimed the political heritage of the Grand Prince of Vladimir, attached itself to the moral and institutional power of the eastern Orthodox church, and had grown in wealth and population as it took over neighbouring principalities. But the civil war proved a political vortex, shattering clan and dynastic relationships, and drawing in Moscow’s neighbours. As Muscovy recovered, the victorious prince, Vasilii II, began to re-establish the political authority of his throne.

MAP 1 Western Eurasia, c.1400 (adapted from map on www.euratlas.com)

The accession of Ivan III to the Muscovite throne in 1462 was a pivotal moment in Moscow’s political and military development. Most dramatic of all was its uneasy international situation. For Moscow, the uncertainties that followed the collapse of Mongol control were nearly as intimidating as they were liberating. Several potential heirs to the Horde’s power were poised competitively on the steppe. To the south and east of Moscow were three rival khans, all members of the Mongol royal family. A senior khan led the Greater Horde near the mouth of the Volga, north of the future Khanate of Astrakhan. Another member of the royal family ruled the Khanate of Crimea, across the steppe to Muscovy’s south. The last, the Khanate of Kazan, was on the northern Volga directly east of Moscow. Southeast of the khanates were the Nogai; this nomadic people laid no claim to the Mongol heritage, but often proved a vital ally for those who did. Muscovy’s attitude toward the three khanates was ambivalent. Any re-creation of the Golden Horde’s former all-encompassing control under the Great Horde was not in its interest. At the same time, Moscow’s commerce depended upon trade routes that crossed the steppe, which were less well protected under the Horde’s successors and Moscow’s current rivals. From 1450 to 1520 such geopolitical considerations motivated Muscovite policies towards the khanates more than its religious and cultural dissimilarities with them.2 That is, Muscovy often cooperated with the Khanates of Crimea and Kazan to prevent any resurgence of the Great Horde.

To the west of Muscovy, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, since 1385 linked to Catholic Poland by a dual monarchy under the Jagellonians, had grown significantly more powerful in the aftermath of Mongol collapse. As recently as the reign of Vitovt (d. 1430), Lithuania had annexed lands within 240 kilometres (150 miles) of Moscow, adding to the number of its subjects who were Orthodox Slavs. The size of its Orthodox population had more than once led the Grand Duchy to challenge Moscow’s preeminence in the Russian Orthodox church. Since Lithuania and Poland stretched south to the Black Sea, the dual monarchy also controlled lands on the western end of the steppe, crucial parts of trade routes running southwest from Moscow. In short, the Grand Duchy was itself a strong contender for steppe prominence as the Golden Horde divided into smaller entities. Earlier in the fifteenth century, Lithuania might have seemed even more formidable than it did in 1450. In the mid fifteenth-century, however, interruptions in the Baltic trade and political disarray following Vitovt’s death had somewhat diminished its influence.

As it recovered from civil war, Moscow had little difficulty in seeing itself as the only remaining north Russian contender for power on the steppe.3 By the early 1400s Muscovy controlled not only Moscow and its hinterland, but had absorbed Vladimir and other territories as well. In the middle of the fifteenth century a number of independent principalities still coexisted with Moscow in the north, some more autonomously than others: Rostov, Iaroslavl, Tver, Riazan, as well as the prosperous commercial centres of Pskov and Novgorod. Despite the impressive territorial dimensions of Novgorod in particular, these principalities were militarily no match for Muscovy. If they were not contenders with Moscow for the role of the Horde, these northeast Russian principalities were concerned with protecting themselves from Muscovite encroachment. Lithuania’s proximity and size encouraged them to appeal to the Grand Duchy for aid and support to balance Muscovite expansion. Relations among these close Russian Orthodox neighbours were thus frequently tense, if not precisely over the future of the steppe.

Muscovy by 1460 was thus a regional power naturally concerned with the international power shifts left by the collapse of the Golden Horde. Its neighbours, both Islamic khanates on the steppe and contentious east European states, shared this international orientation. Nearly all of them had become embroiled in the Muscovite dynastic wars under Vasilii II. Ivan III’s activities, which signalled a newly aggressive Muscovite foreign policy, initiated a new round of international tensions.

A new political consensus

Muscovy’s ability to negotiate this demanding situation depended particularly on two closely linked domestic arrangements. One was the transformation of its political structure; the other, the military organization to which politics was so closely linked. In the aftermath of civil war and reconstruction, neither political nor military structures were formal or institutionalized. Political power was patrimonial and unregulated. It was measured by personal relationships at the royal court in Moscow, where the reigning Grand Prince ruled in conjunction with the heads of major clans or families. By the 1460s, these powerful figures included boiars from up to 15 Moscow-based clans, as well as allies, service princes and men of the Muscovite royal family – specifically, Ivan’s four younger brothers. In addition, the court included a less powerful but more numerous population of courtiers (dvoriane) and other serving men (deti boiarskie) who might owe allegiance directly to the Grand Prince or to another of the elite figures just mentioned.4 These men served the Muscovite Grand Prince at court and on the field of battle for a variety of reasons. Some princes had been vanquished by Moscow’s army, while others were no doubt both intimidated and attracted by Moscow’s growing might. Less exalted, but still wealthy and important, families were also drawn to the Muscovite court by its superior military and political power as well as sheer wealth in land, servants and trade goods. Loyal service to Moscow thus held the promise of rich rewards. If only one could be noticed amidst the cut-throat competition at the court, status and riches greater than those available in most nearby principalities might be won by nobles and courtiers. For the Grand Prince, maintaining stability and a ruling consensus among these competing figures was a necessary precursor to any international or military success.

Boiars were leading men, representing powerful clans and associated webs of personal alliance, clients and servants. By the middle of the fifteenth century Moscow’s boiars consistently came from a fairly stable group of families. Boiar families supported themselves in large part from lands, purchased or bestowed on them within or near the Principality of Moscow. Acquiring new lands allowed a clan to expand support to its family members and clients. Although these formidable clan groupings competed with one another for high status at the Grand Prince’s court in Moscow, boiar families after the civil war conceded the need to cooperate with the ruler’s assertion of power. Clan feuds and rivalries served only to tear the court apart, destroying the source of the wealth and power that each clan hoped to attain. The dynasty, for its part, solicited advice from its chief courtiers and resolved matters with their consent.5

These boiars were, above all, a warrior elite. Military prowess won them prominence in their clans and at the Muscovite court. When they attained exalted rank, they attended the court and acted as political advisers. At the same time, they continued to serve in military capacities, leading their retinues into battle and commanding their sovereign’s troops.6 Boiars’ retinues, made up of free men and slaves and drawn from their relatives, clients and servants, were declining in size and importance by the 1460s.7 Instead boiar advancement was reflected in positions of correspondingly higher trust and authority in the sovereign’s forces. Boiars and their associates might also be appointed viceregents (namestniki), temporarily governing lands in the name of their prince in return for ‘feeding’ (kormlenie) by the local taxpayers.

By contrast with the boiar clans, most service princes were recent arrivals at the Muscovite court. Royalty and recently independent rulers in their own right, these princes were forced into Moscow’s sphere because their lands had been conquered; because they had been intimidated by Moscow’s growing power; and because war had impoverished them. Others were attracted by opportunities for advancement; although loyal service to Moscow meant a loss of independence, in return it offered access to wealth and power that only Moscow commanded.8 Service princes did not all join Moscow in the same way. Some of them attended court in Moscow but still essentia...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Maps

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Chronology

- Introduction

- Part I 1450–1598

- Part II 1598–1697

- Part III 1698–1730

- Glossary

- Index