eBook - ePub

Elevating Student Voice

How to Enhance Student Participation, Citizenship and Leadership

- 132 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Elevating Student Voice

How to Enhance Student Participation, Citizenship and Leadership

About this book

This book demonstrates what schools can do to enhance student participation and engagement. It shows educators how to:

- create opportunities for students to practice democracy and civic responsibility.

- develop a "school for each kid"

- get students to care Examples include

- Community service

- Peer Helpers

- Peer Mediators

- Student-directed programs and events

- Student feedback to teachers

- Student-led conferences

- Students on interviewing committees

- Students on the School Board

- Student publications

- Student speakers

. . . and more

Also highlighted in this book are the exciting and enriching activities of First Amendment Schools.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Elevating Student Voice by Nelson Beaudoin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Changing the View

Getting Students to Care

Even if we were to disregard all the research that identifies how students learn, all the programs that promote learning, and all the beliefs that support it, we would be left with one compelling reason to embrace student voice, and that is the difference it makes to students. By elevating student voice to its rightful status, we can change the way students view their learning, themselves, and their school. This change sends out ever-widening ripples. By listening to student voices, we can motivate and engage students in today’s schools, and that engagement can lead to greater achievement. High levels of student engagement open the door to improved pedagogy, program innovations, and reform initiatives.

The problems of disenfranchised youth in America’s schools go far beyond the factors—such as teacher shortcomings, poor facilities, inadequate funding, low test scores, societal issues, and lack of accountability—that usually get top billing from critics of our educational system. Those critics who do address low levels of student engagement link it to other factors, only rarely considering student engagement in its own right. By contrast, I view student engagement as the linchpin of great schooling. Unless we engage our students—unless we get them to care—not much else will matter.

Greeting students on the first day of school, I exchanged pleasantries with a returning senior I’ll call Tim.

“How was your summer?” I asked.

“Not long enough,” he answered.

“They never are, but it’s good to see you again.”

As I began to walk away, Tim stopped me. “You know, I was thinking about you the other day,” he said.

Somewhat intrigued, I asked how in the world I had entered his thoughts during summer vacation. Tim explained that he had thought about how hard I worked at making the school better, by giving students freedom and encouraging them to act responsibly. Smiling in appreciation, I started to walk on. Tim’s next words stopped me in my tracks.

“But in a way, I feel bad for you,” he said.

“What do you mean?” I inquired.

“Well, I feel bad because, you know, some of our students just don’t care! You do all this work and some people just don’t care!”

My response was swift and instinctive. “Oh, thanks so much for thinking of me, but don’t be concerned. I realize that some students don’t care. But I can tell you that ten percent more care than cared the year before, which was ten percent more than the year before that. I know I can’t possibly get everyone to care, but as long as the numbers are going in the right direction, I intend to keep doing what I am doing.”

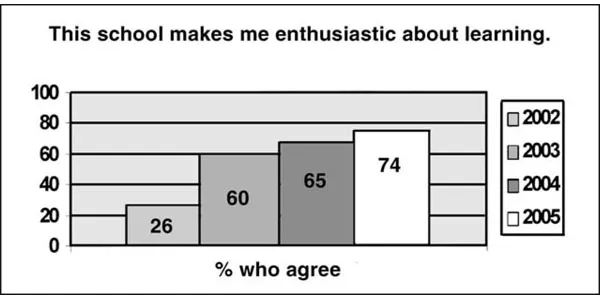

My response was based on survey data about Kennebunk High School students’ enthusiasm for learning, collected over the previous four years. As Figure 1 illustrates, the data show a dramatic increase in positive student responses to the question, “Does this school make you enthusiastic about learning?” I attribute that increase to attitudes, practices, and programs that improved student engagement by promoting student voice. We can change the view. We can get kids to care!

Figure 1

A School for Each Kid

Many years ago, an ad campaign for McDonald’s restaurant chain used the slogan “We do it all for you!” to suggest that customers needn’t worry about decisions when ordering food: “Two all-beef patties, special sauce, lettuce, cheese, pickles, onions, on a sesame seed bun!” In contrast, the Burger King franchises chose a different approach: “Hold the pickles, hold the lettuce, special orders don’t upset us!” Burger King’s slogan was “Have it your way.”

I’m not going to make judgments about fast-food restaurants—but if the slogan “We do it all for you!” described a school, I think it would be a “school for all kids,” where all students take practically the same program involving core subjects in a very traditional setting. At a school that says, “Have it your way,” students would participate in a variety of personalized programs that honor their strengths and interests. This is a “school for each kid”—and I support this approach. Rather than trying to get all kids to fit the same structure, I want each student to find a structure that fits. Rather than having individual students following predictable courses of study, I want them to pursue passions leading to adventurous learning. I don’t view students as spectators who let education happen to them. School is about students, and their participation is nonnegotiable.

The words of this Monte Selby song capture this idea quite well:

“All students in reach, when we find their rhythm

The step, the dance, the song within them.

That’s a better journey, but so much harder.

Too extraordinary, but so much smarter.

To drum to the beat of each different marcher.”

Most schools would have all students march to the beat of the same drum. I advocate a substantially different approach—developing “a school for each kid.”

During a state review last year, six parents were asked to identify the most impressive outcome of their child’s education at Kennebunk High School. In different words, each parent gave essentially the same response: “Our daughter [or son] learned self-advocacy skills.” It stands to reason that self-advocacy is more likely to occur in “a school for each kid.”

After the 2004 commencement, I received the following note from a graduating senior:

Mr. Beaudoin,

I can’t thank you enough for the countless opportunities and support you gave me this past year. Between tutoring in the writing lab and speaking at the school board meetings,I truly feel that I have left a lasting impression on KHS. I could not have done that without you. Kennebunk High School is extremely fortunate to have you.

Thank you again and I will keep in touch.

Fondly,

Eileen

In a departure from the typical thank-you note, this student writes of her contribution to the school. A school that works to personalize programming for each student, to accent their strengths and interests, sets the stage for students to feel a strong sense of accomplishment. Rather than looking at school solely from the standpoint of what it did for her, Eileen was able to look at what she contributed. John F. Kennedy understood that a volunteer spirit would advance citizenship: “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.” We will return to this idea of service as an important aspect of “a school for each kid.”

A Sense of Belonging

The National Center for Student Aspirations3 works to help students live up to their greatest potential. The Center’s work has identified eight conditions that create optimum chances for success. Reading between the lines of Eileen’s brief note, we find the three foundational conditions: belonging, heroes, and a sense of accomplishment.

Eileen’s note definitely gives the impression that she belonged in our school community. Students who have this sense of belonging rarely miss school; they know their absence would be noticed. The fact that Eileen tutored in the writing lab meant that other students depended on her for academic support. She was also a drama student, and the production company would have suffered had she missed school.

Eileen had heroes—adults she could look up to, who listened to what she had to say. As the student council’s historian, Eileen had the responsibility of reporting student council activities at monthly school board meetings. School board members, drama coaches, teachers, administrators, and parents were important to Eileen, and they all showed a willingness to listen to her.

The final foundational condition speaks about students having a sense of accomplishment. Clearly, Eileen believes she has made a difference in her school community. She undoubtedly saw her time in high school through a lens of giving, rather than a lens of receiving.

The National Center for Student Aspirations also lists three motivational conditions: fun and excitement, curiosity and creativity, and a spirit of adventure. As we investigate ways to get students more engaged in their school and their learning, these motivational conditions will come into play. So much of the incentive for learning is found in these conditions, and student voice can have a dramatic effect in advancing them.

The Center rounds out its list of conditions underpinning student success with two that imply a lifelong mindset of aspirations: leadership and responsibility, and the confidence to take action. These too will surface throughout this work, particularly when we address civic responsibility and democratic practices. The idea that students should be given opportunities to lead, to make decisions, and to experience the consequences is really about creating citizenship skills.

Eileen’s words support the major theme of this chapter: Schools that set out to create “a school for each kid” can engender a sense of belonging in their students more readily than schools that treat all students the same. Schools can promote this sense of belonging in many ways, from simply caring about the students personally to providing special activities that honor students’ strengths and interests.

Choosing a reluctant learner as the “keeper” of the classroom pencils offers a simple example of giving students a sense of purpose. Teachers who assign classroom duties contribute to a sense of belonging in their students. When done thoughtfully, constructing classroom chores can have a positive effect on learning outcomes and student accountability. All students can grow from these experiences that promote individual value and teach responsibility.

School clubs and organizations foster the sense of belonging that is so critical for young people. While budget discussions often sideline athletic teams, art programs, and school clubs as dispensable, they provide strong opportunities for drawing students in. Many students identify with the teams, clubs or activities they join. These co-curricular and extracurricular pursuits give students a reason to come to school.

Kennebunk High School, a school of 850 students, offers other examples of how students build a sense of belonging. Every Wednesday, the class day at KHS starts 90 minutes later than usual so teachers can work collaboratively to improve teaching practices and school programs. Most of the students love the opportunity to sleep in, but a significant number (approximately 15 percent) come to school at the regular time.

Some of these students have a special group or activity they don’t want to miss, such as Writers Club, Captains Club or Chess Club. But many of the early morning crowd come to school simply because they feel comfortable there. For some, home is not all it should be. Others come to be with their friends; young people need to socialize. Regardless of the reason, I’m glad to see students wanting to come to school. They belong here!

Students also demonstrate this sense of belonging at Kennebunk High School during the 45 minutes after the first bus arrives. Before the start of the class day, students are free to go anywhere in the building in a peripherally supervised situation (a few adults are on duty in general areas). What we see during this time on a typical day highlights the concept of belonging.

In the upstairs hallway near the elevator, ten sophomores sit on the floor. Four of them are playing a battery-operated game—a game designed for younger children, but these fifteen-year-olds are having a blast. The same group gathers here daily, mostly to study and hang out with friends. If any one were absent, the other nine would notice.

Another swarm of about 30 “regulars”—a real cross section of KHS students—starts the day down the hall in Mr. J’s room. Some are playing chess, others a complex fantasy card game, still others a spirited round of Battleship. A few are simply talking about the weekend’s NASCAR race. Mr. J is playing in one of the card games. Whether he knows it or not, he is providing these students with a home base, a place of belonging that boosts their enjoyment of school.

Similar gatherings form throughout the building—some because of a special bond with a teacher, others because of a particular interest in sports, or shared academic curiosity, or a social relationship. It’s not a bunch of cliques; the point is that students have the freedom to roam, to make themselves comfortable. The time honors who they are and encourages their sense of belonging.

Teenagers have a monumental need to fit in, a fundamental need to belong. Schools can help them meet this need simply by acknowledging its importance. Furthermore, I believe that for a school to succeed, its students must have a sense of belonging at school. A great many of the other topics explored in this book contribute to this important idea.

Bonnie Benard4 is a strong national voice in the work around resiliency in the fields of prevention and education. In her research on the benefits of environmental protective factors to student success, she cites three factors that have held up under scrutiny: caring relationships, high expectations, and opportunities to participate and contribute. T...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- Meet the Author

- INTRODUCTION: THE MAGIC OF STUDENT VOICE

- 1. CHANGING THE VIEW

- 2 CHANGING THE PRACTICE

- 3 PAYING HEED TO STUDENT VOICE

- 4 LINKING CLASSROOM AND COMMUNITY

- 5 SHOWCASING TALENTS, BUILDING SKILLS

- 6 EDUCATING FOR CITIZENSHIP

- 7 HIGHLIGHTING THE FIRST AMENDMENT

- 8 FINDING INSPIRATION FOR THE JOURNEY

- CONCLUSION: CLOSING THE CIRCLE

- BIBLIOGRAPHY