![]()

Part I

Philosophy and film

![]()

1 What is philosophy?

Philosophy is the art of asking questions. Not just any questions. Most philosophical questions cannot be answered conclusively, and yet every conclusive answer to any other kind of question presumes that they are settled: questions about the way things are, what is of worth, what counts as knowledge, how we can arrive at it, and what we should do about it. The aim of asking questions is to clarify our ideas regarding themes such as reality, knowledge, ethics, and beauty – notions at the heart of everything we do and experience. The clearer our ideas become, the more it becomes clear that these are subject matters open to question. To think about them is to enter into an open-ended conversation that has been going on for centuries.

Philosophical questions

“What is that?” a child might ask. “A fish.” But what is a fish? There are easy (and obvious) answers, both everyday and scientific, and any good answer designates the fish as a kind of living thing. If we ask, though, what is life and what is a thing, we begin to move into philosophical terrain where the answers aren’t so easy (or obvious). Much of the work of biology, for example, can proceed under the assumption that what “life” means is well understood. Yet in special moments of discovery – say, of an unusual substance on another planet or deep in the ocean – the question whether something should be considered a life form may very well arise. In such moments the investigating biologist or chemist or marine geologist is compelled to operate as a “philosopher of nature”: to raise anew the question just what it is to be alive, to ask where precisely to mark the division between the living and the non-living. For philosophical questions, moreover, it is not enough just to ask; it is necessary to highlight the difficulties that make the questions inevitable, which is to say, to show the conflicts and contradictions in our ideas and practices that require working through. Such discoveries signal the need for an inquiry in which there are no easy answers, but in which new answers can help us see things differently, illuminating connections we hadn’t suspected.

The question about “things” may seem like a silly one. We know about all kinds of things: animals, people, movies, rocks, and less tangible things like emotions and ideas. We rarely (if ever) consider what makes a thing a thing, or what these very different kinds of “things” have in common. It is this question, however, that formed the primary subject matter of one of the foundational texts of Western philosophy, Aristotle’s Metaphysics. He considers there what it means to say something is a “substance,” which he defines as a thing whose reality does not depend on anything else. He shows that we can distinguish between a substance and its properties, as well as between a substance and its activities and movements. Emotions, then, are not substances. They are not real things. Instead, they are ways in which substances – including human beings – can be affected. Ideas are more complicated. Some seem like they don’t exist apart from the individual substances (people) who think about them. Other ideas, such as the idea of a number, seem to have properties that are independent of whatever anyone happens to think about them, and so seem to be real all by themselves. They aren’t just thought up. They’re discovered. Indeed, one of the basic and persistent philosophical questions is whether ideas are real in their own right or whether their existence derives from the individual realities (or substances) they refer to and describe. Do concepts exist independently of thinkers? Do they exist apart from the things they refer to? These seem to have been subjects about which Aristotle disagreed with his famous teacher Plato.

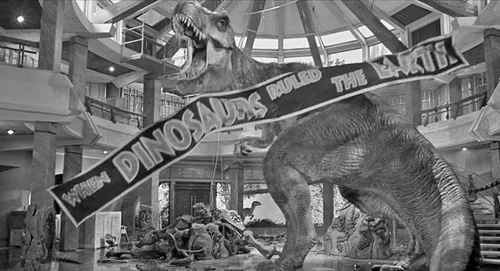

Figure 1.1 Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (1993).

To illustrate some of the issues, we might consider briefly whether a film can be considered a substance. A film is certainly something, but it isn’t immediately obvious what kind of thing it is. Take, for example, the film Jurassic Park (1993), directed by Steven Spielberg. It isn’t a natural thing. It’s made. It is a specific thing, with features that make it different not only from other kinds of things, like fish and chairs, but from other things of the same kind, such as other films. At the same time it doesn’t seem to be just a single thing, like a specific fish or a chair, because there can be many different copies of it – the original negatives, the 35mm prints from which it was originally projected, DCP drives that might be sent out to modern theaters for digital screenings, Blu-Rays and DVDs for home screening, online streaming files, etc. – and each one might be said to be the film Jurassic Park. It isn’t just the total group of these copies either, because you could destroy all but one of them without destroying the film.

We might, perhaps, consider films to be analogous to animal species, such as, for example, the Tyrannosaurus Rex. Aristotle considered species to be secondary substances, where the individual members of a species were primary, which means they exemplify more fully what it is to be a substance. Still, while there can’t be a species unless there are at least some individual members, the reality of the species is more enduring. As long as at least some individual T-Rexes existed, the species still existed. Yet the species is not just the sum total of living individuals. Even now, when there are no such individuals, we can still talk about the species, and can say we know roughly what it would be like for something to be a T-Rex. There is still something it is to be a Tyrannosaurus Rex, and it is this fact that makes it possible to conceive that some future technology might allow us to bring them back. That is, after all, the premise of the film Jurassic Park. The current non-existence of living individual T-Rexes may not mean that the species has ceased to exist. What it is to be a T-Rex – the defining conception that allows us to think about them, to recognize them in images and descriptions, to make movies about them even after their extinction, and, at least in principle, to bring them back using advanced cloning techniques – that is at least partly what Plato had in mind when he held that ideas (or forms) transcend their instances.

Still, it is not just the defining conception that allowed dinosaurs to come back in Jurassic Park. John Hammond and his team of scientists needed dino-DNA. They needed not only the information coded in the DNA, but a mechanism for inserting that information into modified frog DNA, initiating the causal sequence that would allow them to hatch dinosaurs in the laboratory. Similarly, it would not be enough just to have the idea of the film Jurassic Park. In the absence of a negative, or a film print, or a digital file, Jurassic Park, the film, would cease to exist. It would, like some of the lost works of great philosophers, exist at most in memory and historical records. The most one could do is create a remake based on the original script, and that would be a markedly different thing. The performances wouldn’t be the same, and neither would the moving images, even if some portions could be duplicated. So while the film Jurassic Park is not identical with the sum total of existing copies, it couldn’t exist unless at least one of them exists or enough parts of it exist somewhere to enable a complete restoration.

Even that might not be enough. In a future world, perhaps so far into the future that the existence of human beings could only be inferred from our remains in the way that we have learned about the dinosaurs, even if it happened somehow that a DVD or a digital file of Jurassic Park still existed, it wouldn’t make sense to say the film itself existed unless there was also the technology to play it and beings capable of watching it. Without some way of reading the data and translating it into the moving images that make up the film, these “copies” would be useless. It wouldn’t be clear what they were copies of. Similarly, dinosaur DNA, trapped inside of a mosquito trapped in fossilized amber, is not the same as a dinosaur. It is among the material conditions that make it possible for dinosaurs to exist, but it isn’t a dinosaur until it takes on the form of a dinosaur. We might think about this in terms of the distinction between potentiality and actuality that Aristotle sometimes employs in his Metaphysics to discuss the nature of substance. Dinosaur DNA may have the potential to become a dinosaur, but it is actually just a complex molecular structure that won’t produce anything unless this potential is actualized through the fertilization of an egg. Even a fertilized dinosaur egg is only potentially a dinosaur, and it isn’t substantially a T-Rex until it actualizes that potential and hatches. Only after hatching is it capable of acting as we expect baby T-Rexes to act and, furthermore, of then growing up into a mature dinosaur. Only then would it fully exemplify the kind of independent being – the kind of substantial reality – we associate with T-Rexes. Likewise, we might say, a DVD or a digital file of a film is only potentially a film. It is actually a film only when this potential is actualized, when the film is played using the appropriate equipment and screened for an audience. If this is so, though, it seems we were wrong to think of the film as a kind of substance. It is not something that can exist on its own. It exists to be shown, and can only be the film that it is and tell the story we associate with Jurassic Park when it is screened for an audience capable of perceiving it. Still, if it is not a substance, it is not nothing. It is at least something real.

Whatever it is, it is clearly not the same as the material stuff that makes it possible to watch it. Perhaps the reality of the film is best characterized as a process, that of screening the film for an audience. Only as that process is realized is it truly the film, only then does it exhibit the distinctive qualities we associate with this film. The many copies of Jurassic Park that exist around the world in various forms are not really the film itself, any more than the fossilized DNA of a dinosaur is the dinosaur itself. You can’t have the film without some copies, just as you can’t have a dinosaur without dinosaur DNA. But the film itself is the reality that unfolds for an audience each time it is screened. Arguably, while the audiences may respond differently, and the conditions of each screening will vary, it is the same film they are watching each time. So, if the movie Jurassic Park is just one thing, it is the thing that audiences get to watch every time it is screened. We’ll examine much more closely just what kind of thing that is in the third chapter. For now, though, we can say that even while it may not make sense to speak of a process that unfolds over time as if it were a substance, this doesn’t make film all that different from entities that on Aristotle’s terms are clearly substances, such as dinosaurs. The being of a dinosaur is not something that exists all at once in its entirety. It is something that unfolds over time, from the moment that the egg hatches to the moment that the dinosaur dies. Moreover, the dinosaur’s existence at any given moment is not static. It is and can only be the dinosaur that it is by engaging in characteristic activities such as hunting, feeding, and sleeping. These activities, moreover, are only made possible by the ongoing mechanical, chemical, and biological processes taking place inside the organism. Similarly, a film like Jurassic Park can be what it is only as a result of technical processes that make its screening possible. Its reality depends upon these processes. Moreover, it is not something that can simply exist only for a moment, or even forever. It is a finite reality that takes up space and occupies time. It exists – it is the film it is — only in the time it takes to screen it, and in a suitable place it can be screened; and since each screening is roughly the same, each person who sits through it can say that they’ve seen Jurassic Park.

Metaphysics, the inquiry into the nature of reality and into the question what is ultimately real, is one of the basic subject matters of philosophy. Each of philosophy’s primary subjects — metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, and aesthetics – is defined not by a body of information or teachings, but by a set of questions and a (historically developing) series of (increasingly sophisticated) concepts in terms of which answers can be explored. What makes these subjects primary (and perennial), and what makes the questions philosophical, is that they are at the heart of every other inquiry. To answer any other questions requires that we take answers to these questions for granted. Any inquiry into what is real, or into why things are the way they are, presumes an acceptance that there is a reality and that we can somehow make sense of it. It supposes a rudimentary grasp of the nature of things, of the nature of change, and of what counts as explanation. Claims to know (or even believe) anything rest on some grasp of the nature of belief and of criteria for knowledge. To make moral judgments is to presume that people are free to choose what they do. It would be unreasonable to say that someone had done wrong if they were not capable of acting otherwise. To claim that someone has done wrong also presumes that there are standards for action, and that these standards can be justified. It would be unreasonable to expect someone to adhere to a moral standard that they were not aware of or didn’t accept, or that, at the very least, could not be defended and justified with reasons that they could endorse. Finally, our experiences of art and beauty and our assessments of their worth presume at least some rudimentary notion of what art is, and some sense for a difference between what is and isn’t beautiful. The assumptions needn’t be (and often aren’t) fully spelled out or thought through. Still, everything we do or say rests on some assumptions regarding, among many other things, existence, causality, truth, knowledge, right and wrong, art, and beauty. To do philosophy is to consider all of these assumptions, to examine whether there are good reasons to accept them, to determine whether they are consistent, and to explore the implications of other ways they might be spelled out.

The point of all this effort is to figure out and clarify how we really ought to think about the way things are and ought to be. We think all kinds of things, and our actions imply a number of assumptions about the world. For the most part, however, we haven’t thought things through. We inherit the assumptions we use to make sense of the world. Even those working in established disciplines – whether in the natural or social sciences, or in the humanities, or in business – operate with established methods and work from ideas and theories about how things work and why. Such methods and ideas may have stood the test of time, but they aren’t timeless or inevitable. They could be challenged, and often are. When the notions we’ve inherited no longer serve to make sense of what we experience, whether in our everyday lives or in our highly refined expert practices, it is time to let go of established assumptions, ask new questions, and sort things out differently. That is what philosophy is all about – except that philosophy does not wait for the crisis, when our concepts and assumptions no longer match our experience. Philosophy aims to show that the core assumptions at the heart of our experience are always open to question.

So philosophy begins by asking open-ended questions. To explore these questions requires that we make distinctions. Of course, to make distinctions also involves drawing connections between apparently disparate things, things that share a distinction in common. We have so far distinguished between philosophical and non-philosophical questions, and have distinguished between the four primary philosophical subjects, and at the same time shown that these diverse themes are connected. They are all focused on what we might call “fundamental questions,” questions at the heart of all inquiry and action, whose answers are presupposed by both theories and practices.

Philosophy, myth, and religion

Traditionally, myth and religion have provided answers to these fundamental questions. Stories about the gods and sacred writings taught about reality; temples and sculptures of deities and other religious works of art provided inspiration; songs and ritual practices motivated and instructed peoples how to act. Yet stories of the gods still require interpretation and explanation. Philosophy begins when the answers provided by religion and myth are treated as a starting point for new questions. That a god – or God – laid down this or that decree begs the question what it means and why it should be followed, and who or what is God, and how can we know his will or that he is at all (or that God is a “he”)? A ritual begs the question what is its purpose and value? To ask such questions is not to reject religion, or to reject the importance of the stories people tell to make sense of things they cannot fully understand, and the rituals and practices they employ in order to orient their lives around what they consider to be of ultimate importance. It is, rather, to see that religion, myth, stories, images, and rituals are of worth, at least in part, precisely because they provide groups of people with beliefs and practices that contribute to their identities, and shared cultures they care about, and can thereby demonstrate the importance of sorting out what it means and why.

The first major Greek philosopher we know about was Thales of Miletus. He is most famous for his proclamation that “all is water.” The claim is not as absurd as it might seem to be at first. Water is, after all, ubiquitous. The lands the Greeks inhabited were dwarfed by vast and uncharted oceans. He had postulated, as well, that earthquakes resulted from the fact that the Earth floats upon water. There are waters in the heavens that pour down in the form of rain, and water vapors can be observed to condense from the air. All living things, moreover, depend upon water. Water, like film, takes on an almost endless variety of forms and is always in flux.

Yet Thales also proclaimed, cryptically, that “all things are full of gods.” That may suggest he is not so far from myth, that he considers changes taking place in nature to result from supernatural forces, or divine intervention. The point may also be more subtle, however, since if things themselves are full of gods we needn’t look elsewhere, as to Mount Olympus, for an explanation of their activities. It suggests that the explanation of their movements is contained within things themselves, right there in front of us, and that to understand their nature requires that we observe and study nature, rather than wait upon muses or soothsayers to reveal the hidden will of gods.

Many other Greek sages in the aftermath of Thales sought also to understand the natural world without a direct appeal to gods. They considered what underlies and causes natural changes, reflected upon the nature and possibility of change, and sought to identify those things that do not change. Their inquiries were, fundamentally, attempts to identify principles, the most basic and core truths or realities that help explain and make sense of everything else....