- 340 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Design and Build Contract Practice

About this book

This edition covers the principles of the design and build system of construction and examines the detail of the operation.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part 1

Basic aspects

Basic aspects

Chapter 1

Client needs and contract solutions

The employer’s aims and needs in building

Some contractual alternatives

The design and build alternative

There is a wide range of solutions to the problem of how to arrange contractually for building work to be carried out. The persons most directly affected are the building client (referred to in most chapters in this book as ‘the employer’) and the contractor. They, after all, respectively either pay for the work or perform it; and their concerns are widely discussed in this volume.

The reasons for so many contractual solutions, lie either in economic trends, in passing or recurring fashions, but also in the nature of building. Leaving aside the speculative housing sector, involving ‘contracts of sale’, the ‘contracts to build’ sector embraces new work and alterations on all scales, related to many types of construction. In addition, the employer may be an individual, a partnership or one of a variety of public or private corporate bodies. For some, commissioning building work is a once-in-life-time experience; for others, it is part of or even the whole of their activity,. Thus contractors have developed in various ways to meet the needs of different employers.

A number of contractual approaches have developed in this environment and become ‘traditional’ over the last century or so; however, in recent years several alternatives have come forward. The evolution of these traditional approaches is now a matter of history; the fact is that they all incorporate the use of professional consultants in a similar way. Architects, engineers, other designers and quantity surveyors have separate contracts with the employer and work in the communications gap between him and the contractor, who has a contract solely with the employer. There is thus a separation of design and its cost control from construction, not only because there are distinct specialists in each, as is almost inevitable, but because the functions are performed by different organisations which exercise limited control over one another. The strengths and weaknesses of this structure are mentioned in Chapter 2.

Among other things, these newer alternatives usually seek to amend the communications structure; thus project management either introduces a further consultant or elevates an existing one to co-ordinate the activities of everyone else. Some would say that the architect has traditionally fulfilled this task and is well placed to continue doing so. Management contracting puts the contractor into the position of project management, while retaining the individual consultants. However, neither of these alternatives is taken further in this book, which is about the more radical alternative of ‘design and build’, as used for the whole or part of a project.

Design and build is the umbrella term also covering package contracting, the all-in service, develop and construct, and turnkey contracting. Package is a shorthand for design and build, meaning the performance of both functions in one ‘package’, that is by the contractor as a single contractual person; however, he may parcel out the work to his own consultants. It usually carries the connotation of system or industrialised building, such that the project can largely be selected from a catalogue or by viewing an already existing example. All-in service is a direct, if vague, equivalent of design and build. Develop and construct requires some design work by the employer or his consultants, which the contractor takes over and ‘develops’. Any scheme, of course, requires some briefing from the employer, even if it is only the provision of a schedule of accommodation resulting from a minimal amount of briefing. It is thus at one end of the spectrum of design and build. The idea of a turnkey contract at its most embracing is that the contractor acquires the site and secures all approvals for the client in addition to designing and building and installing all plant, equipment and even furnishings. The employer simply has to ‘turn the key’, walk in and start using the place. These latter two vary the design and build theme respectively at the beginning and the end, without destroying it. While they are not referred to explicitly, they are accommodated within design and build, which is widely used hereafter.

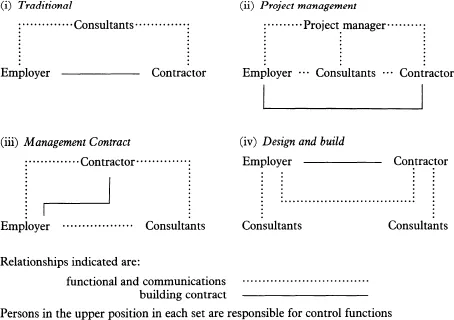

Table 1.1 Building contract relationship

The effect of design and build is to move the consultants from the gap position between employer and contractor and place them under the sole authority, and possibly within the permanent organisation, of the contractor, whom they alone advise. As a counteraction, the employer may then engage further consultants to give him independent advice on some issues. This is similar to the pattern of many other industries, which do not separate design and production in the way that construction does. It has its strengths and weaknesses, which are mentioned later in this chapter, and will become apparent in further discussion.

The essence of the distinctions drawn so far is presented diagrammatically in Table 1.1. While commercial forces do in time lead to changes and while fashions rise, fall and revive, it is not unreasonable to suggest that there is no optimum procurement pattern at any one time. Within this diversity, some (by no means all) employers are looking for simplicity and economy, while, to satisfy them, some contractors are promoting design and build.

In the main, this book refers to employers and contractors, who are taken to include their various consultants to avoid constant repetition. The special positions of consultants do raise some distinct issues, which are treated in Chapter 3.

The employer’s aims and needs in building

Different contractual solutions have different effects in furthering the employer’s aims to meet his needs; they regulate various aspects of the bargain with differing precision. Since not all employers’ aims are the same they are best served by these various solutions. In general the employer states what he wants, where and when, together with any budget limits; the precise detail is usually worked out by others. Aims like those set out below tend to influence where the boundaries are drawn. This section outlines the more prevalent aims which may be recalled in later discussions, where some but not all are referred to specifically.

Satisfaction of function

This is the primary aim for any employer, in the sense that unless he has certain needs to be met, and unless the proposed building meets them, he will not commission it at all. This is true whether he wishes to use or sell the product and whether, say, it is intended for personal enjoyment, commerce or industry. The simplicity or complexity of function may vary widely, whether the building’s purpose is intended to be static or change during its life: in all cases the employer’s needs must be met. This also is a truism, but worth this brief emphasis especially concerning concepts like design, performance and fitness for purpose. Contracts and the law do not always meet ‘common sense’ expectations fully on these points.

Function, taken alone, is concerned at the macro-level with design which provides facilities which work well, assuming adequate materials and workmanship are always provided. This therefore needs specialised design, ahead of construction. Among those who supply design are, for example, a generalised specialist in design, such as an architect or structural engineer who may have wide competence and insight; or a specialist in a particularly narrow area of design, such as a refrigeration engineer, with his depth of knowledge and, possibly, construction experience. There are ready arguments for and against each of these performing particular design work, although there appears little in favour of the specialist in construction work who is not also a regular designer, especially when providing the broad scheme design.

Achievement of economy

This means gaining the best result, which may not necessarily be the cheapest, for what the employer is prepared to spend. ‘Best result’ begs a lot of questions, that must be answered by the other aims. At the lowest level, if the employer cannot afford it at all he cannot have it, whatever the function, aesthetic or economic return. Three sequential areas of economy may be instanced which overlap each other.

The first is strategic and less a matter of building design: where to locate the building geographically in relation to site characteristics. This may be fixed by prior ownership of a site, or there may be a range of sites available with a programme of building works phased over years. The advice that the employer needs may come from within his own organisation or need special consultancy. This precedes and is distinct from design, whoever performs it.

The second area is design itself where, within the context of ‘value for money’, there is need to control the initial costs. These are the amounts paid for the design and the construction, and the costs of financing them, including the loss of use of money owned or borrowed which is paid out on account and on which there is no return until the building is in use. The concerns of employer, designer and constructor must all be met, for it is the employer who actually pays out; the designer has his design liability to protect; and the constructor has a profit to make. Separate cost advice on the design and control of what is paid is a way of limiting the problems.

The third area of economy is still design, but in relation to controlling the continuing costs after construction, and so the total or life cycle costs. These include operating the building (particularly staffing and energy), cleaning, maintenance and repair, alteration and adaptation, and depreciation to the point of sale or demolition, with disposal costs. Again, the concerns of the various people involved must be given consideration, and this may be complicated by any tension between initial and continuing costs. These should be resolved by a properly discounted calculation of total costs. Unless the employer is given the full picture for the life of the building, he may be misled as to the efficiency of the design or designs which are offered in a set of tender figures. This is especially the case when contractors are in competition over design as well as construction.

Within all these factors the level of the tender and the final settlement must be considered. This is influenced by the economic climate, the degree of competition and the contract arrangement used. Some of these control expenditure more tightly or at least more predictably than others. Design and build has the advantage that both its functions are within or controlled by one organisation, which may be a potential factor for economy, although an incentive to economise is needed.

Control of programme time

For some employers, this may be the tail that wags the dog strongly, or even irresistibly takes control. Properly considered, it is a sub-set of economy, often viewed in relation to the construction period alone, when the employer is paying out his largest sums of money and the contractor has continuous site overhead costs. These elements have to be balanced against the efficient purchase and use of the other factors of production on and off site, which in turn affect the contractor’s costs allowed in his tender. The whole programme should be considered from the first clear articulation of the need for the project to the time at which it might come into use. This should be viewed in relation to the subsidiary optimum time for total production economy. The need to meet a fixed date for public or commercial reasons may be extremely strong, or funds may be available only in a limited flow, so compressing or extending this time.

Following on from the above, there would be an apportionment within the whole programme of the various elements. Whoever does what, there must be a brief supplied as ideas are clarified; development of a design and entering into a contract; and construction and handing-over. These are often regarded as discrete and sequential activities, and certainly there must be clarity as which is to be performed and when, to give a balanced programme. Almost invariably these activities, while distinct in concept, overlap in time if only because a project can be broken into smaller parts proceeding at various speeds. These same activities may be subject to reiteration as design throws up questions. In addition to this built-in, cyclical effect, there may be a conscious overlapping of the activities to achieve compression of the overall programme. This may work well, so long as reiteration does not then undermine the work of later stages with too many changes.

All contract arrangements, by definition, give an absolute demarcation at the stage of entering into the contract: some require complete design before tendering, some allow design to continue during construction, although ahead of the section conc...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1 Basic aspects

- Part 2 Practice and the JCT contract

- Part 3 Alternative approaches

- Part 4 Table of cases and indexes

- Subject index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Design and Build Contract Practice by Dennis F. Turner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Construction & Architectural Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.