![]()

I

Understanding the Children’s Television Community

![]()

1

The Television Tug-of-War: A Brief History of Children’s Television Programming in the United States

Donna Mitroff

Rebecca Herr Stephenson

University of Southern California

The history of children’s television programming in our culture spans only about 50 years. Dr. Mitroff’s career as a practitioner in the industry has spanned nearly half of this time period. She began watching TV as a child when television was a new, exciting addition to family entertainment. Ms. Herr Stephenson’s career in the industry is just beginning; however, she grew up during the years when the presence of television and the choices in children’s television programming were ubiquitous. We have had remarkably different experiences with children’s television programming and yet we share the belief that there is a constant interplay between what is happening in society at large and in the broadcast and cable industry and that this interplay frequently has a trickle down effect on the content and themes of children’s television programs.

This chapter attempts to outline the major societal events that have occured during the lifetime of the mass media in the United States and draw connections between these events, the structure and products of the entertainment industry (with a focus on the television industry), and children’s television policy and programming. It is important for readers to note that we are not historians. The historical overview sections of this chapter are not intended to serve as complete analyses of American history. Rather, they are intended as snapshots of American history during different decades. These historical snapshots are provided for the purpose of orienting readers to the major events and societal trends of the historical periods. Furthermore, this is neither an exhaustive investigation of all themes and examples present in children’s programming nor a definitive examination of the relationships between the cultural forces and the products of the entertainment industry. Rather it is the first product of a line of research we plan to expand in future work.

The first part of this chapter explores the overarching premise that all media is a reflection of the context in which it is produced. As a cultural artifact, media, like art or literature, reflects cultural concerns, societal trends, philosophical, moral, and religious beliefs, and reactions to world events. Media produced for children is certainly not exempt from the impact of context. Perhaps because of its perceived educational duty, children’s media has, in several instances, reflected societal changes and concerns before those same elements appeared in general audience programming. The story of children’s television in the United States is one of a delicate balance between governmental regulation, advocacy by concerned citizens, and reactions by those in the industry. By and large, the children’s television industry has stepped up to the challenge of assisting children in understanding and adapting to a changing society, and continues this work in the face of the challenging issues encountered by children (and adults) today. There is, however, constant negotiation between the desire to shape children’s programming around children’s educational, informational, and socioemotional needs and the perpetuation of television as a business.

In the second part of this chapter, we present a more detailed analysis of the way in which the children’s television industry has addressed the issue of violence. We look at three examples of industry reactions to violent events in society and present a variety of strategies employed by producers in the children’s television industry to help children understand, cope with, and learn from violent events.

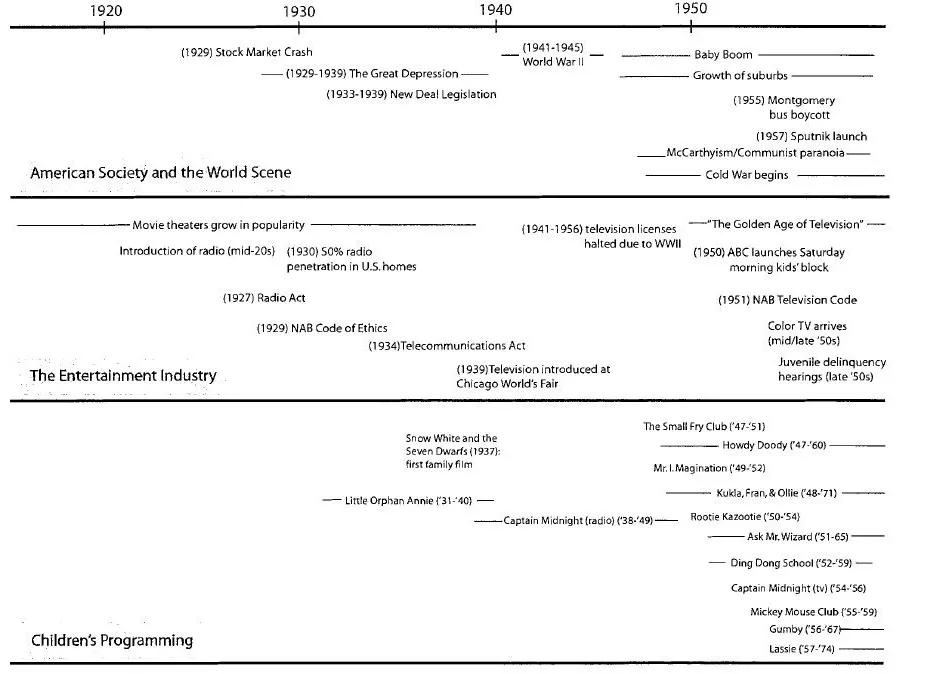

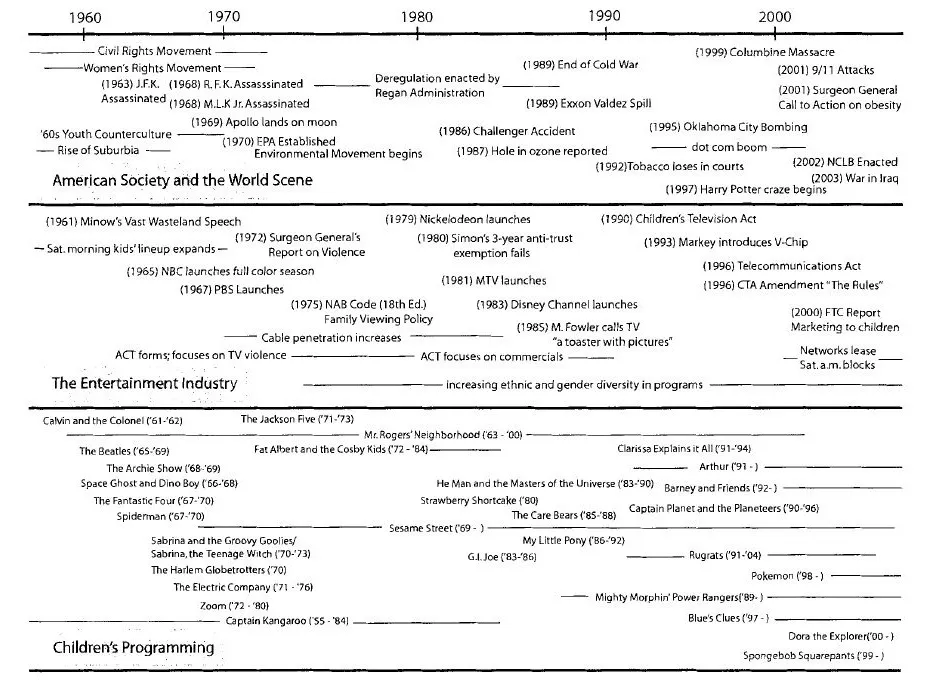

To provide an overview of how society and the children’s programming arena have interacted over the years, we have developed a timeline (see Fig. 1.1). The timeline illustrates important events within American history, media history, and policy, and television programming for children. Discussion of the timeline will focus on the interplay between events and societal trends, public policies (in particular those related to the regulation of television), and the content of children’s television programs. This interplay is illustrated with a variety of examples drawn from children’s programs within each historical period.

Figure 1.1 HIstory of Children’s Programming

Part I: Examination of the Timeline

The 1920s and 1930s

American Society and the World Scene. The 1920s were years of transition in the United States. The end of World War I left many Americans disillusioned and unsure of the value of their sacrifice. The resurgence of business power and the expansion of industry brought a wave of materialism that made some question whether the idealism and social consciousness of the previous progressive era was lost. Nevertheless, the 1920s were a time of prosperity. Skylines expanded upwards, roads were built to accommodate additional automobiles, and new homes were erected to house the growing population. The national census of 1920 showed greater population density in urban centers than in rural areas; the impact of this demographic change was felt throughout the 20th century. The prosperity felt by some Americans was not a luxury of all citizens, however. Discriminatory legislation against new immigrants attempted to slow population growth in urban areas. Prejudice against ethnic minorities, particularly African Americans, was prevalent in several regions of the country, allowing the spread of the Klu Klux Klan beyond the south. Conservative morality tangled with science in the inflammatory Scopes Trial, and was felt again in 1918 when the passage of the 18th Amendment made prohibition the law of the land. The stock market crash of 1929 marked the end of the prosperity of the early years of the decade and signaled the beginning of the Great Depression. Unlike previous depressions, the impact of the Great Depression was felt most sharply by the middle class—the same people who had benefited most from the postwar economic boom. The New Deal programs enacted by Franklin Delano Roosevelt offered hope to the struggling middle class, promising work programs and protection of investments. Although unemployment remained relatively high through the end of the 1930s, the basic economic system survived. By the end of the decade, the focus of the nation was drawn to the growing threat of international aggression from the three totalitarian countries: Germany, Italy, and Japan (McDonough, Gregg, & Wong, 2001; Schlesinger, 1993).

The Entertainment Industry. The history of children’s television programming begins with the story of the first two forms of electronic entertainment to permeate society: movies and radio. As movie theaters and radio stations developed during the 1920s and 1930s, children were a major target of both forms of media. The Saturday matinee was established to provide entertainment for a young audience. Early on, these matinees showed short films and newsreels. However, as the popularity of films in the youth market was demonstrated, studios began to produce family films. The family film genre was initiated with Disney’s release of Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs in 1937 (Paik, 2001).

By the middle of the 1920s, movies had become an important form of entertainment for American families (Paik, 2001). However, the privileged status of film was challenged by the introduction of radio. By the end of the 1930s, half of the homes in the United States had radios and listening had become a family affair. As the penetration of radio increased, its major source of revenue shifted from the sale of radios to the sale of commercial airtime. The establishment of networks proved to be an efficient system for a group of stations to share costs and provide larger audiences to advertisers. Thus, the network model was firmly ensconced by the end of the 1930s (Alexander & Owens, 1998).

Regulation of this new national medium was enacted in 1927 with the Radio Act, which established the concept of the airwaves as public property, and mandated the creation of the Federal Radio Commission (FRC). In an effort to avoid further governmental regulation, the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) developed a Code of Ethics and Standards for Commercial Practice, a self-regulatory act that was put into place in 1929. The Code prohibited “offensive material,” “fraudulent, deceptive, or obscene matter” and “false, deceptive, or grossly exaggerated” advertising claims (McCarthy, 1995). The Code was employed alongside the FRC mandate. The FRC was disbanded when Congress passed the Communications Act of 1934 and shifted responsibility for the regulation of radio to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). The Communications Act of 1934 mandated serving the “public interest, convenience, and necessity” as the basis for granting broadcast licenses. Defining the public interest, particularly as it relates to groups with special needs (such as children) has been a challenging and contentious process (Minow & LaMay, 1995). Debates over the public interest obligations of broadcasters resurface regularly. In recent years, the argument has become increasingly complicated by new technology and media conglomeration.

Despite concerns over regulation and serving the public interest, radio continued to grow throughout the 1920s and 1930s. It was soon demonstrated that children would follow serial dramas, identify with fantastic characters, laugh at comedy, and most importantly, influence family purchasing patterns. Radio producers and sponsors began to view children as a valuable audience and programs specifically for children increased. Although mainly intended for entertainment and to advertise the sponsor’s product, many of these programs contained references to societal concerns. For example, the program Little Orphan Annie addressed the collapse of the economy, unemployment, and labor unrest. Captain Midnight told the story of Captain Jim Albright, a brave aviator in World War I, and thus encouraged nationalism and gratitude for the efforts of military personnel. Captain Midnight, as well as the Green Hornet, Tarzan, the Lone Ranger, and Buck Rogers became immortalized figures in American culture through radio programs, and many have reappeared in other media forms, including comic books, television shows, and animated films.

At the end of the 1930s, a technology was introduced that would challenge the status of both film and radio. Television was exhibited for the first time at the 1939 World’s Fair in Chicago, with the promise of the electronic delivery of news and entertainment in both audio and visual form directly to American homes. However, the growth of the television industry was stalled at the beginning of World War II when the FCC stopped issuing broadcast licenses because of the need to direct efforts into the development of technologies for the war effort (Barnouw, 1990).

The 1940s and 1950s

American Society and the World Scene. America’s participation in World War II began in 1941 when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and continued through September 1945. The war was almost unanimously supported by the American public despite domestic injustices perpetrated by the government, such as the internment of Japanese Americans in work camps. The surrender of Germany and Japan to allied forces secured the United States’ position as a world power, and the postwar years were marked by a growing economy and widespread prosperity. Large numbers of returning servicemen took advantage of the G.I. Bill of Rights, which enabled them to attend college and buy homes, setting the stage for the huge baby boom in the United States. The Interstate Highway Act of 1956 connected the sprawling suburbs that surrounded every city. The 1950s were good years for the growth of the White middle class in America. African Americans, in spite of their service in the armed forces during World War II, were not equal participants in the growing middle class. Their frustration fueled the boycott that launched the civil rights movement and introduced the country to the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr.

The era also brought the commencement of the Cold War defined by the arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union, and the policy of containment of the spread of Communism that included America’s entry into the Korean conflict in 1950. Paranoia over Communism set off a wave of suspicion, which led to searches for Communists living in America. Spearheaded by Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). The anti-Communist crusade came to be known as “McCarthyism,” and invaded the government, the entertainment industry, higher education, and the literary community. America’s confidence in its political, technological, and educational superiority over the Communist system was shaken when the Soviet Union launched Sputnik into the earth’s orbit in 1957 and set off the “Space Race.” The new mood in America set the stage for a change from the old order to the new youthful energy of the Kennedy era (Alexrod, 2003; Schlesinger, 1993).

The Entertainment Industry. The FCC resumed granting television station licenses in 1946. The following decades saw a decline in movie attendance and radio use, and an extremely rapid penetration of television set ownership, leading to the designation of the 1950s as “the Golden Age of Television” (Barnouw, 1990). Programmers, advertisers, and networks quickly learned that children often influenced parents’ decision to purchase a television; therefore, providing programming for children became a priority in the early years of television. By 1950, 10% of American households owned a television set. By 1955, set ownership was up to 67% of U.S. households (Baker & Dessart, 1998).

The first NAB Television Code, adopted in 1951, was almost immediately attacked by the ACLU as illegal censorship. It contained explicit content restrictions on displays of violence and sexual content (Minow & LaMay, 1995). By the end of the 1950s, television was no longer the darling of the public. Widespread concern about juvenile delinquency led to hearings on the link between children’s behavior and the images shown in popular television programs. Chaired by Senator Estes Kefauver, who also authored a Reader’s Digest article entitled “Let’s Get Rid of Tele-Violence,” these televised hearings raised the level of public awareness and concern about violence and television (Hoerrner, 1999).

In 1947, Small Fry Club, the first daily 30-minute program designed specifically for children, went on the air. The show’s host, Bob Emery, later played Buffalo Bob on the Howdy Doody show which debuted in December, 1947. (Davis, 1995). Howdy Doody, the marionette star of the program, was so popular that in 1948 he received more write-in votes for President of the United States than the independent candidate (Stark, 1997). In these early days of television, programming for children was not restricted to Saturday morning nor limited to hours before and after school. Many shows, such as Mr. I. Magination, Kukla, Fran and Ollie, and Super Circus were aired in the evening and viewed by both adults and children. Fischer (1983) reports that Mary Hartline, who appeared as the baton twirler on Super Circus, was so popular that she became “a topic of conversation throughout the nation” (p. 23). Rootie Kazootie, a Little Leaguer who appeared on national television from 1950–1954 as Little League Baseball was skyrocketing in popularity, illustrates the appearance of popular themes in programs.1 Not all programming aired during this time was originated by the networks; frequently, a show created by a local station would move to the national networks. One example is Space Patrol, which was first shown locally in Los Angeles and later was aired nationally on ABC (Fischer, 1983).

As the Baby Boom generation grew up, fueled by a steady diet of children’s television programming, shows were introduced that contained allusions to Cold War concerns, including surveillance, secret agents, and post-war paranoia. These shows reflected the rampant anti-Communism sentiment of the McCarthy era. The popular radio drama Captain Midnight reappeared on television and was on the air from 1954 until 1956. Captain Midnight was a unique opportunity both to expound Cold War themes and create consumer loyalty to the sponsor, Ovaltine. The Ovaltine Company made it possible for children to see themselves as special by providing for them the opportunity to se...