![]()

Part I

Redefining Bioclimatic Housing

![]()

Chapter 1

Definitions, Concepts and Principles

Richard Hyde and Harald Røstvik

Introduction

The aim of this chapter is to discuss some of the current definitions, concepts and principles for bioclimatic houses and housing.

Source: Richard Hyde

1.1 Redefining bioclimatic housing can start from studies of built works: Mapleton House, subtropical Queensland, Australia. Richard Leplastrier is one of the contemporary Australian architects whose architectural ideas have had a significant impact on its architecture. Mapleton House, located in subtropical Queensland, provides insight into new definitions, concepts and principles (architect: Richard Leplastrier)

First, an examination of bioclimatic architecture is given. This demonstrates the increasing importance and relevance of bioclimatic design to solving some of the emerging issues of the 21st century – namely, the concern for the state of the environment. It suggests that bioclimatic design can be a means of implementing international policy, such as the Kyoto Protocol, through a reduction of energy use and other environmental impacts. Hence, if bioclimatic design is the means, then sustainability is the outcome. New definitions and standards are emerging, which are now called sustainable development; therefore a discussion is provided in this chapter of some of the assumptions about the notion of sustainability in the context of sustainable development for buildings.

Generally, because of the multidimensional nature of sustainability, it is often difficult to conceptualize what sustainability means unless it is described with reference to a particular context. This is because being sustainable brings to a phenomenon the idea of being able to maintain its condition or state. The sense of the temporal and the future are an important dimension to the discussion of sustainability. More commonly, sustainability is discussed with reference to the operation of natural systems, with particular reference to the way in which natural resources are used and managed. Exploiting natural resources without destroying the ecological balance of a particular area is a key requirement of being sustainable. Currently, international policy has described the need for sustainable development as a means of achieving this end.

From these definitions have arisen new concepts for houses. New terminology has developed to describe these concepts. Countries such as the UK refer to eco-houses and carbon neutral housing, while from Australia there is SMART housing. All seem to have a similar but different interpretation of the relationship between the form and fabric of housing and living organisms and climate. What can be drawn from this diversity helps with the task of redefinition. Interesting aspects from this rich variety of concepts bring new ideas and priorities. Some argue that to be ‘green’, housing should be autonomous in terms of its servicing – that is, the building should not be connected to mains services. Other concepts emphasize the quality of life provided by these types of homes – that is, homes that are healthy for the occupants and healthy for the environment.

Principles have arisen which are useful to the building professional. The work of Brenda and Robert Vale is used as a basis for describing a range of principles that are generally applicable to green design but can be modified to the specific needs of housing in warm climates. The objective of this book is to assist with redefining principles for bioclimatic housing in warmer climates.

Finally, an example of how these principles have been applied to a domestic building in a developing country (Sri Lanka) is provided in Case study 1.1. This case study is of importance because it shows the need to view bioclimatic housing in its social context. To state the obvious, housing is primarily a social challenge; yet, often its relationship with climate and living organisms is lost, particularly in developing countries. Achieving a sustainable future in these countries is as much a bioclimatic issue as a social issue.

Case study 1.1 Media Centre, Colombo, Sri Lanka

Harald N. Røstvik, Architect

Profile

Table 1.2 Profile of the Colombo Media Centre, Sri Lanka

| | |

Country | Sri Lanka |

City | Colombo |

Building type | TV studios and media centre |

Year of construction | Completed autumn 2001 |

Project name | WGM |

Architect | Sivilarkitekt, Harald N. Røstvik in association with Kahawita de Silva Ltd |

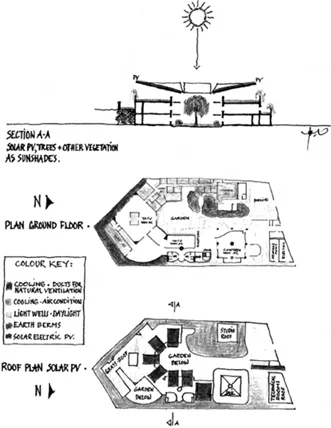

Source: Harald N. Røstvik

1.19 Media Centre, Colombo, Sri Lanka: front elevation

Portrait

Buildings account for close to 50 per cent of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. Instead of being polluters, can buildings and even whole cities become solar power stations? Leading ecological designers now suggest that they can and must.

In time, can a sun-blessed country such as Sri Lanka be connected to the sun and be free of dependency upon imported fossil fuels? With the help of well-designed ecological architecture it possibly can.

What, then, is sustainable design? The answer will be different in different contexts. The approach must be determined by local factors: climatic, economic, technological and, not least, cultural.

The Media Centre in Colombo contains a range of ecological features. It is an example of climatic adaptation and innovative sustainable design. It also addresses the growing trend of putting up slick glass buildings regardless of the climatic and cultural context.

Context

The design of the 3000 square metre building was developed with a Norwegian firm as lead architects in collaboration with a Colombo firm. Most of the consultants were Sri Lankan; but the specialist energy consultant, Max Fordham & Associates in London, supported the local know-how base and the heating, ventilating and air conditioning (HVAC) consultant Koelmeyer. All contractors, with the exception of the solar system contractor (Engotec GmbH in Germany), were local. The local University of Moratuwa provided input studies. Transfer of knowledge and awareness-building played a key role in this North–South collaboration.

Economic Context

The building contains workspace for up to 450 people, including visitors. The several private companies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that occupy it and built it were previously scattered throughout Colombo in five or six different buildings, resulting in communication problems and unnecessary traffic. Each had their own canteen, stores and toilets.

By co-locating these different units, a more rational use of space was made possible. This has resulted in a space reduction of up to 30 per cent and, hence, a reduction of material use as well as of energy needs. The Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD) supported part of the ‘green package’ of technologies; but most of the funding came from the visionary client itself. The ‘green package’ has had an extremely tight budget, which considerably restricted the project.

Site Description

The site in Battaramulla, close to the new parliament, on the outskirts of Colombo was chosen to move the occupants out of the polluted city centre of Colombo. The site was sloping and the building cut right into the slope. All trees were preserved in order to shade the building. The concept is that of a lush garden with no vehicle access, thus greatly reducing vehicle noise and airborne pollution in the working environment. Vegetation and external window shades, along with solar photovoltaic (PV) modules that ‘float’ over the building as flakes of shading devices, are attempts to reduce the cooling load. Air entering the building is filtered through vegetation for cooling and cleaning purposes.

Source: Harald N. Røstvik

1.20 Media Centre: section showing solar photovoltaic (PV) modules and vegetation as roofs and shade. Plans show the location of solar PV modules. The coloured ‘key plan’ shows natural ventilation ducts, locating which spaces use air conditioning and which use natural ventilation, as well as light shafts that allow daylight into the offices

Building Structure

Most of the building is three storeys high, while part of it comprises two storeys. The roofs are shaded with great sails or solar modules, and there is the possibility of incorporating working spaces beneath the roofs as long as there is no rain. The building contains several split-up divisions, all shaded or covered but in the open air. Rooms within each division are arranged mostly as an open plan or, where closed rooms are necessary (editing rooms, etc.), along a corridor. There is no basement; but since the site originally was sloped, parts of the building have their ‘back’ towards the earth shelter and are situated underground towards the neighbouring sites. Vertical light shafts are used to bring daylight deep into the building, where possible.

Most of the building is naturally ventilated and lit. The parts that must have air conditioning due to the need for a stable temperature are the technical rooms (studios and editing rooms). These have split-unit air conditioning with an economy cycle on the cooling system to improve energy efficiency.

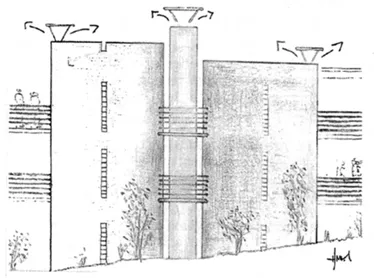

Source: Harald N. Røstvik

1.21 Media Centre: architecturally visible natural ventilation ducts draw air from interior spaces – cooling is helped by solar PV extract fans

Building Construction

For fire regulation and mass (cooling) purposes, the main structure is concrete and plastered brick. Part of the top floor roof is earth sheltered. The remaining solid roofs are tiled.

The majority of the building was constructed in situ in order to create local employment. Shading devices comprising solar photovoltaic panels and other structures, such as the sails and external window shades, are prefabricated.

Ventilation System

The major parts of the building are naturally ventilated. Huge, wide and vertical (mostly round) ducts project through the building as architectural elements. Inside the ducts are huge ceiling fans. The fans are run directly by low-voltage DC electricity from solar PV panels, which function as a shade and water barrier on top of the duct. These ducts suck air out and naturally cool the building interior through a high proportion of air changes.

Appliances

Throughout the building, energy efficient light bulbs are used. Some of the new computer equipment and studio mixing and recording equipment are chosen with energy efficiency in mind. There is cooling recovery on the AC system in the studio and editing rooms.

Energy Supply System

The overall concept of the building is influenced by the aim of reducing energy needs. The building was the nation’s first to have a grid-connected solar PV system, with a calibre of 25kWp (kilowatt peak: the current/voltage curve for a solar cell; so a 25kWp solar system creates 25 kilowatts of power at peak solar conditions). The base load in the building is, at times, smaller than that and power is exported to the grid. The grid connection of the solar PV eliminates the need for batteries. The hot water supply is intended to be solar thermal, but is not yet installed, nor is the cooking water supply, also planned to be solar thermal assisted.

Solar Energy Utilization

To reduce electricity demand, the building is designed to allow maximum indirect daylight penetration into rooms via courtyards, light wells and patios, cutting vertically right through the building mass.

The common design of ‘deep’, badly lit offices has been avoided. Shading by vegetation, sail cloth and solar PV modules (which ...