![]()

Part I. TOWARDS A CONTEXTUAL FRAMEWORK

![]()

Chapter 1. MANAGING NATURAL RESOURCES: A STRUGGLE BETWEEN POLITICS AND CULTURE

1.1 From local livelihood strategies to global agro-industrial markets

Filder is at work in the family’s shamba. She is harvesting cassava today, and worrying about the disease that seems to have attacked so many of the new plants. Wondering what she could do to prevent further spreading, she resolves to discuss the problems with some of her village friends later in the day. In her mother’s shamba on the outskirts of Kampala, cassava still grows well. Perhaps she could walk there, one of these days, and get some of her mother’s cuttings to try in her own fields.

The new portable machine has been set under a shack on the side of the grazing fields and Tobias is gathering the cows for milking. The machine could easily service many more cows than he has, but his quota for the year is already filled. Fortunately, the farmers’ political lobby in Switzerland is very strong. Tobias and colleagues just celebrated their most recent victory against a motion to lower agricultural subsidies in the country. With subsidies at the current level, twenty cows are enough to gain an excellent income.

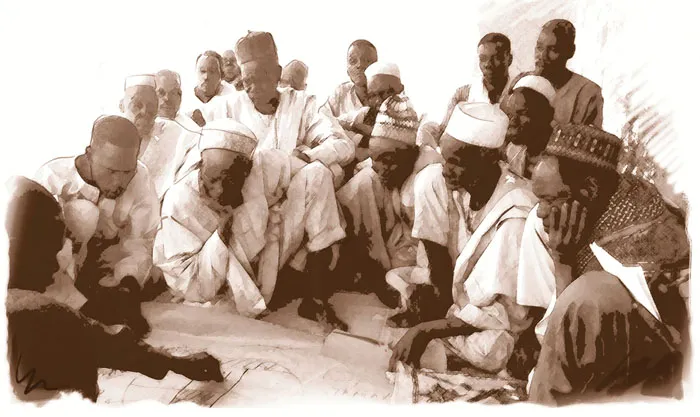

Erika has just survived one of the two annual meetings of the Consultative Council of the Protected Areas Authority of which she is in charge. She is exhausted but satisfied. The discussion was lively and the people had so much to say. The new local administrators seemed not entirely at ease, but the representative of the cattle owners and the one of the environmentalists were extremely vocal and everyone now clearly knows where they stand. She goes back in her mind to the pictures of the degraded areas she showed in the afternoon, against the backdrop of the whitest peaks and one of the most untouched old-growth forests in Romania. These were impressive images and she is sure they will be discussed by the working group in charge of developing a draft management plan in their forthcoming meeting, just a week from now.

The minga, a weekly day of communal work, has just ended. Colourful people scatter back home on the chequered green and brown landscape of the Andean hills. Rosario and twenty other people representing all the village households gathered in the morning to plant lentils and oats in the plot of hard soil they are all recuperating together. For some months they moved the earth and fertilised it with animal manure, and are now halfway into the process. Once the oat and lentils are harvested, they will mix the remains into the soil, and add some more manure. In the next growing season they will be able to plant maize and potatoes. They will finally have managed to add some productive land to the meagre resources of their community.

This is one of the most important deals of Mark’s stockbroker career in New York. He puts down the phone having reached an agreement that will change the price of cocoa for some time, and his client will profit from it. The new price will eventually encourage more people to produce and process cocoa, and the supply may rise too much in a not-so-distant future. This is not his immediate concern. He just needs to call his client and announce the good news of the deal.

Fatima had just gathered the yews and she-goats within the stone enclosure. As she milks the animals, she thinks about the quality of grass in the pasture. The nomadic pastoral elders are about to meet and decide the date, length, itinerary and size of the migrating herd for the entire Qashqai sub-tribe, one of the largest tribes in Iran. Some months ago she and several other women collected a good quantity of quality grass seeds. Tomorrow they will place them in perforated goatskins, and append those to the neck of the lead goat. As the animals roam, the seeds will come out gradually and will be ploughed under and fertilised by the marching flocks. The rangeland will improve after the next rains and better quality pasture will be available on their return from the summering grounds.

What do Erika and Filder, Fatima and Tobias, Mark and Rosario have in common? Not much, seemingly. Yet, the daily work and decisions of all of them impact upon the natural environment. They are all “natural resource managers”.

For some of them, the interaction with natural resources and the environment is a direct and intimate affair. Learned in the household and the community, it is an integral part of what makes life normal, convivial and safe, what makes them a member of a group and a culture. For others it is an acquired and rather distant power, mediated by technology, sophisticated information systems and big money.1 Still for others, in rapidly growing numbers in the urban sprawls of the world, that interaction is both distant and relatively uninformed. Many of us eat food we have not grown, consume electricity unaware that it comes from burning fossil fuels or from nuclear power plants, use and pollute water without considering that we are subtracting it from environmental functions with no known alternative.

For some [natural resource managers], the interaction with natural resources and the environment is a direct and intimate affair.… For others, it is an acquired and rather distant power.…

For the vast majority of time in which our species roamed the planet, the interaction between humans and the environment has been of the first kind. Early groups of Homo sapiens may have impacted upon the environment in a substantial manner (mostly through the use of fire)2, but were also in the front-line to see and feel the results of their own action. More recently, modern technology and the globalisation of the economy allowed for some on the planet to have an interaction with natural resources that is at the same time very powerful and very remote. This is a unique characteristic of modern times, built up in recent millennia through social diversification, the diffusion of travelling and exchanges, the intensification of agricultural and industrial production and the progressively imposed domination of the market economy.3 Below we will discuss, on the basis of field examples, how such intimate and remote interactions with the environment co-exist today, and how they clash or integrate with one another. To arrive at that, however, we will start from some general considerations.

A human culture is a set of institutions, practices, behaviours, technologies, skills, knowledge, beliefs and values proper to a human community. As such, a human culture is usually received, lived, refined, and reproduced at any given moment in history. In traditional societies, many of the features proper to a culture can be interpreted primarily as a response to the specific natural environment where they need to gain their livelihood. Much of what differentiates Ugandan peasants from Mongolian herders, French wine makers, or Japanese fisher-folks can be traced back to environmental factors such as landscape, climate, water availability, type of soil and the existing flora, fauna and mineral wealth. By no means are these the only determinants of the cultures that developed in their midst, but they provided the crucial set of external conditions around which different cultures developed their characterising features. Among those features are the organisations, rules, practices, means, knowledge and values allowing communities to exploit and conserve their natural resources. We will refer to these as “natural resource management (NRM) systems”. Another term used to represent the set of conditions that regulate the reproduction and use of natural resources is “NRM institutions”. In this work we will use the term “institutions” with reference to NRM systems strongly characterised by social rules and organisations.

[Many cultural differences can be interpreted in the light of specific] environmental factors, such as landscape, climate, water availability, type of soil, and the existing flora [and] fauna.…

An NRM system regulates the interplay between human activities and the natural environment. Its major outputs include:

• human survival and the satisfaction of economic needs through productive activities, such as hunting, fishing, gathering, agriculture, animal raising, timber production and mining;

• the transformation of portions of the natural environment into a domesticated environment, more suited to being exploited (e.g., clearing of agricultural land, irrigation, management of grazing land and forests);

• the control of natural environmental hazards (e.g., preventing floods, fighting vectors of disease, distancing dangerous animals from human communities);

• the control of degradation and hazards caused by human pressure on the environment, through more or less intentional forms of conservation of biodiversity and sustainable use of natural resources.

A feature closely related to NRM systems is the social regulation of population dynamics. The technological and social capabilities to exploit natural resources (in particular food resources) are a major factor in shaping the size and density of human populations. For instance, communities featuring an NRM system based on agriculture and animal husbandry are usually larger in size and more concentrated than hunting-gathering communities. In general, an increase in human productive capability may result in an increased community size. Yet, that same increase is one of the main problems NRM systems need to face. If a population grows beyond a certain limit, the existing territory may become unable to support it. Some common solutions involve the migration of a sector of a community towards uninhabited areas and the intensification of local production by adoption or invention of newer or more effective technologies and practices.4 Dominant neo-Malthusian theories maintain that these solutions are far from being available to all communities, and many NRM systems are today stressing their environment, at times beyond the point of recovery. More balanced analysis would show, however, that in nearly all such cases, some social, economic and political factors outside of local control are playing a dominant role. Too often, unequal terms of trade, land grabs and natural resource alienation by governments and private actors impinge on the community NRM systems and drive them to stress their resources much beyond the traditional sustainable practices.

The technological and social capabilities to exploit natural resources (in particular food resources) are a major factor in shaping the size and density of human populations.

All NRM systems include elements explicitly addressing the conservation (including wise use) of natural resources, such as knowledge of the local environment, technology and know-how. Examples of these elements are hunters’ knowledge of animal behaviour and self-restraint in time of mating and growing of the offspring, regulation of grazing and fishing rights in indigenous communities, modern farmer capacity to use fertilisers, and community—or state-promoted watershed management schemes.

…control over land and natural resources—in particular closure and limitation of access and use—has also been a pervasive area of social struggle.

Many conservation features embedded in NRM systems, however, are not explicitly meant for the purpose. Rather, they are embedded in other components of a culture (social organisation, magic and religious beliefs, prevailing values) but have a significant impact on the interaction between a human community and the environment. For instance, a religious taboo preventing hunting during the breeding season, on the surface not inspired by a preoccupation for the conservation of game, may still be an effective means to avoid over-hunting and over-fishing. A rule establishing distribution of the camel herd among the children of a Bedouin head of household may be meant to ensure a fair share of wealth among the community, but could also be useful to avoid unsustainable grazing in given locations. The belief that land is a “gift from God” is a religious sentiment, but it may also motivate farmers to practice sound land husbandry. A sweeping land reform may be a political move to pacify the rural and urban poor, but may also have important consequences on the type and intensity of agricultural practices.

…a religious taboo preventing hunting during the breeding period, on the surface not inspired by a preoccupation for the conservation of game, may still be an effective means of avoiding over-hunting.

In fact, the distinction between “natural resource management” and the rest of human life may make more or less sense according to the socio-cultural point of view. Most traditional societies formed relatively closed systems in which natural resources were managed though complex interplays of reciprocities and solidarities. These systems were fully embedded into local cultures and accommodated for differences of power and roles, including decision-making, within holistic systems of reality and meaning. A telling example is described in Box 3.3, in Chapter 3 of this volume. In all cultures, on the other hand, one can also find some explicit social institutions directly related to the management of natural resources. These generally include:

• inclusion/exclusion rules limiting access to natural resources to communities and individuals belonging to special groups based on kinship, residence, citizenship, economic capacity (ownership of land), personal skills or other criteria;

• customary regulations or written laws aimed at making individual use of resources compatible with collective interests (e.g., reciprocity and solidarity customs, taxation system, “polluter pays” principles);

• social organisations in-charge of establishing and enforcing rules, through persuasion, negotiation, coercion, etc.

Often, such elements coalesce around specific use regimes (Box 1.1)

Box 1.1 Natural resources, property and access regimes (Adapted from Murphree, 1997a)

Natural resources are those components of nature that are being used or are estimated to have a use for people and communities. In this sense, what is a “resource” is culturally and technologically determined. Cultures shap...