![]()

Part 1

ANALYSIS AND ASSESSMENT

![]()

1

Perspectives on the Northern Ireland conflict

Since 1969 Northern Ireland has seen remarkable transformations. In the 1960s optimists believed that the economic forces of modernisation were eroding ‘tribal’ divisions. By 1969 rioting could not be controlled by the police and the British army was deployed onto the streets of the United Kingdom. The worst year for violence was 1972 when 496 people were killed as a result of the violence in Northern Ireland; 258 of these were civilians and 108 were British soldiers, 43 from Northern Irish security forces and 85 paramilitaries. Plate 9, a photograph of Martin McGuinness and Ian Paisley sitting together, sharing a joke, symbolises a dramatic change in the attitudes of the leading political figures. Martin McGuinness, who became Deputy First Minister in 2007, was a leading figure in the IRA who believed in 1972 that they were on the verge of victory. In 1972 Dr Ian Paisley was leader of the recently founded hard-line loyalist Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), having made his reputation as an implacable opponent of the civil rights movement. The reputation of these two politicians as hardliners was intact when the IRA announced its first ceasefire in 1994. Yet by 1998 McGuinness’ party, Sinn Féin, had accepted the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) which established power-sharing but left Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom. Ian Paisley’s DUP opposed the GFA and brought down yet another unionist leader, David Trimble of the Ulster Unionist Party, who tried to reach an accommodation with nationalists. Yet by 2007, the ‘Dr No’ of Ulster politics was First Minister of Northern Ireland and sharing power with the former Chief of Staff of the IRA in a double act which became known as the ‘Chuckle Brothers’.

DUP: Democratic Unionist Party, formed in September 1971, since 2003 the largest party in Nort hern Ireland.

IRA: Irish Republican Army, the main paramilitary group, which split in 1969 into two factions – the Official IRA and the Provisional IRA.

Sinn Féin: Political party linked to the PIRA and formed as a result of the split in the IRA in January 1970.

Good Friday Agreement (GFA): Alternative name for the Belfast Agreement of 1998.

This book analyses the transformations of Northern Irish politics since 1969. Why did the conflict emerge and intensify? Why did a power-sharing settlement in 1974 fail when it was so similar to the one agreed in 1998? How do we explain the political impasse after 1974? Did the Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985 have a positive impact on the emerging peace process? Why was the Good Friday Agreement agreed in 1998? What are the prospects for the ongoing peace process?

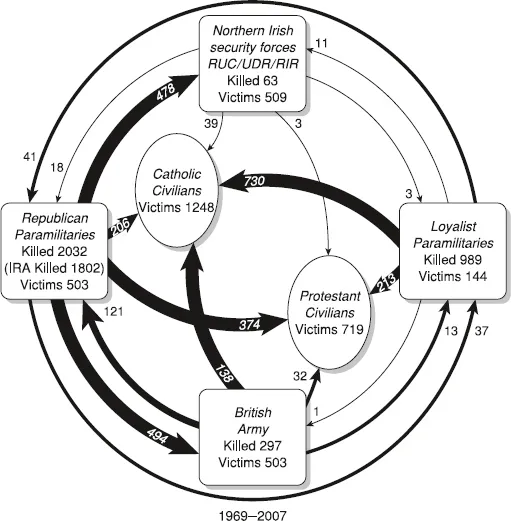

Figure 1.1 Who killed whom during ‘the Troubles’, 1969–2007

Source: Dixon (2008a), p. 29, fig. 1.2.

The interpretation of recent Northern Irish political history is highly controversial partly because of the intensity of the violence. As a result of the conflict, in the period 1966–2006 approximately 3,720 people were killed, out of a population of just 1.6 million. More than half the people in one survey reported that they knew someone who had been killed or injured.

Competing stories are told about the course of events since 1969 in order to justify contemporary bargaining positions and to gain political advantage in the ongoing negotiations of the peace process. This chapter introduces four key perspectives. ‘Nationalists’ are moderates who would like to see Northern Ireland leave the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and join a united Ireland, governed from Dublin, but have attempted to achieve this goal through peaceful means. ‘Republicans’ favour Irish unity but have advocated ‘armed struggle’ to achieve this goal. ‘Unionists’ favour the preservation of the Union between Great Britain and Northern Ireland and tend towards more moderate tactics to achieve this and a greater preparedness to share power with nationalists. ‘Loyalists’ are more militant defenders of the Union and some have supported violent means to oppose Irish unity; they have tended to be less willing to share power with nationalists.

It is important to remember that these perspectives are simplifications of a constantly changing and complex reality. There are also people in Northern Ireland who do not identify themselves as either nationalist or unionist. The term ‘republican’ has come to be associated with the advocacy of IRA violence to achieve the unity of Ireland, but some republicans would strongly oppose the ‘capture’ of the term ‘republican’ by the IRA. The ‘republican’ perspective has radically changed during the course of the conflict from favouring ‘armed struggle’ against the British state up until 1994 and from 1996 to 1997, to power-sharing accommodation within it. A key loyalist perspective shifted from opposition to any power-sharing with nationalists to power-sharing with republicans. Within each of these ideological perspectives are different strands. Catholics overwhelmingly voted for left-wing parties but there was a strong conservative strand within nationalism. Protestants tended to vote for right-wing parties although there has been a significant leftist strand within unionism (Edwards, 2009). Table 1.1 on p. 18 shows the electoral performance of the leading political parties throughout the recent conflict in Northern Ireland.

NATIONALISTS AND REPUBLICANS

Nationalists and republicans date Ireland’s problems from the Anglo-Norman invasion of 1169 and 800 years of English oppression since then. History is a simple and repetitive story of Irish heroes fighting English oppressors: from Cromwell’s massacres in Ireland through the Irish famine of the 1840s, the execution of the leaders of the Easter Rising in 1916 to atrocities perpetrated by the British during the Irish war of independence in 1919–21. The partition of Ireland in 1920 is seen as an undemocratic imposition by the British which created the artificial, gerrymandered state of Northern Ireland. The British could have overcome unionist resistance and created a united, independent state. The British-imposed, unionist-dominated Stormont parliament (1921–71) was responsible for discrimination against nationalists and the oppression meted out by the ‘Orange state’.

Nationalists

Nationalists favour the unity of Ireland but advocate the use of non-violent tactics to achieve this goal. The nationalist view of Irish history and the recent conflict tends to be less antagonistic to the British state than the republicans’, and this has led to a greater willingness to accommodate unionists. In Northern Ireland nationalists are overwhelmingly ‘Catholics’ and tend to be more religious and politically closer to the Catholic Church than their more hard-line republican rivals. The party that has dominated the political representation of nationalists in Northern Ireland is the Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) and its most famous leader is John Hume. There was sympathy for the nationalist position in the British Labour Party and widely among the political parties in the Republic of Ireland.

The SDLP is a centre-left party with working-class support but has performed better than its republican rival among the middle classes [Docs 7, 18, 19, pp. 129–30, 141, 141–2]. The party also had the support of the Catholic Church, which shared its non-violent approach to politics. The founding members of the SDLP had been leading members of the civil rights movement although they struggled to contain the violence that followed. Nationalists were critical of the repressive nature of the police force in Northern Ireland and supported its reform. Initially, they welcomed the deployment of British troops but, as violence and repression escalated, became increasingly critical of the army, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and, particularly, the part-time Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR). The SDLP also strongly condemned IRA violence during the conflict. But the party was also critical of the abuse of human rights by the security forces and refused to encourage nationalists to join the RUC.

SDLP: Social Democratic and Labour Party, nationalist political party, formed in August 1970. The largest nationalist party in Northern Ireland until overtaken by Sinn Féin in 2003.

RUC: Royal Ulster Constabulary, Northern Ireland’s police force from 1922, replaced by the PSNI in 2001.

UDR: Regiment of the British army, formed 1 April 1970 (to replace the B Specials), merged with the Royal Irish Rangers in July 1992 to form the Royal Irish Regiment.

In the founding constitution of the SDLP the party committed itself to Irish unity but only with the consent of a majority of the people of Northern Ireland. Unlike republicans, SDLP politicians tended to believe that it was not the opposition of the British government that prevented Irish unity but the resistance of unionists. While British policy, particularly on security issues, could be repressive, the British political elite was not particularly determined to maintain the Union with Northern Ireland. The problem for nationalists, therefore, was primarily in trying to win the consent of at least some unionists, and the acquiescence of most others, for Irish unity.

In its constitutional policy, the SDLP sought to create institutions, such as power-sharing within Northern Ireland and North–South bodies, which, by demonstrating the material benefits of cooperation, would win the support of a majority for Irish unity. The SDLP, therefore, supported and participated in the failed power-sharing experiment with unionists in January–May 1974. After this failure some within the SDLP were drawn towards support for British withdrawal from Northern Ireland and Irish independence. The principal division within the SDLP was between those around John Hume, who emphasised the importance of the Irish dimension, and those around Gerry Fitt, who prioritised power-sharing and accommodation with unionists within Northern Ireland. From the founding of the SDLP there was significant support for joint authority over Northern Ireland by the British and Irish governments. This would have involved the two governments jointly running Northern Ireland, with unionists in Northern Ireland being represented by the British government and nationalists being represented by the Irish government. The Anglo-Irish Agreement (AIA) of 1985 was strongly supported by the SDLP because it gave the Irish government a formal role in the governance of the North. In the wake of the agreement some in the party pushed strongly for its evolution into full joint authority. Secretly, the SDLP leader, John Hume, successfully attempted to get the IRA to declare a cease-fire and enter into a peace process. This resulted in the Good Friday Agreement which, to a considerable degree, reflected the kind of settlement that the SDLP had been pursuing throughout the recent conflict. Ironically, in the period since the agreement the party has been overtaken by its republican rival, Sinn Féin. The SDLP continues to support Irish unity by consent but, at times, has firmed up its ‘green’ nationalist rhetoric, probably in a bid to shore up electoral support.

AIA: Anglo-Irish Agreement signed by the British and Irish governments, 15 November 1985.

Nationalist solutions

Joint authority/sovereignty

The proposal: the British and Irish governments jointly run Northern Ireland. The British government represents unionist interests while the Irish government represents those of nationalists. This compromise recognises the split loyalties of Northern Ireland’s population and is an equitable way of managing the conflict.

Evaluation: while this appears to be a symmetrical solution it is not. Generally, the unionists do not trust the British government to maintain the Union and would have seen joint authority as a major step towards Irish unity. The prospect of the implementation of joint authority could have provoked a widespread, violent revolt among unionists (see unionist reaction to the more modest Anglo-Irish Agreement in Chapter 5). Opinion polls suggest there was practically no unionist support for joint authority and limited support among nationalists. If it had been implemented the Irish government may have become liable for half of the British subvention to Northern Ireland and it is not clear that the Irish government could afford to take on the North in economic terms.

United Ireland by ‘consent’ (power-sharing and an Irish dimension)

The proposal: the SDLP supported power-sharing with an Irish dimen sion both in 1974 and again with the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. Power-sharing involves the participation of both unionists and nationalists in the government of Northern Ireland. The Irish dimension refers to institutions that promote cooperation between the North and South of Ireland. The SDLP argued that accommodation within Northern Ireland and cooperation between the North and South would lead to a majority consenting to Irish unity.

Evaluation: unionist support for power-sharing with an Irish dimension was limited for most of the recent conflict. Some unionists did support power-sharing in 1974 but the Irish dimension became the focus of much unionist hostility (see Chapter 3). After the collapse of power-sharing the Irish dimension was off the agenda, but unionists struggled even to support power-sharing within Northern Ireland. For much of the conflict, opinion polls suggested that power-sharing was the solution that held out the most prospect of cross-community agreement. The Anglo-Irish Agreement of 1985 did create an Irish dimension by giving the Irish government a consultative role. During the peace process it became clear that an Irish dimension would be part of any settlement; the question remained whether unionist politicians would be able to sign up to such a deal. In 1998 the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) leader did support power-sharing with an Irish dimension and in 2007 the Democratic Unionist Party entered a power-sharing administration with Sinn Féin. It seems unlikely that power-sharing with an Irish dimension will lead to Irish unity (Chapters 7 and 8). Unionist opinion has not wavered during ‘the Troubles’ in its opposition to Irish unity, in spite of growing integration within the European Unity and the Celtic Tiger phenomenon. During the course of the conflict unionist opinion has hardened against Irish unity and there is no evidence that increased cooperation on economic and social matters will lead to political unity.

UUP: Ulster Unionist Party, historically the largest party in Northern Ireland, overtaken by the DUP in 2003.

Republicans

Nationalist is the term that is often used to describe all Catholics, including republicans. In the context of Northern Ireland, ‘republican’ has come to be associated with those who have supported the use of violence to achieve Irish unity and, in particular, the IRA and its political wing, Sinn Féin [Docs 1, 5, 6, 12, 13, 21, 22, pp. 124, 127–8, 128–9, 135, 136–7, 144–5, 146]. There are a variety of strands within republicanism including traditional catholic nationalism, Catholic defenderism, democratic socialism, Trotskyism and other varieties of Marxism. The Provisional IRA (PIRA) represented a more right-wing, Catholic and militaristic republicanism when it split away from the Marxist Official IRA (OIRA) in 1969. The PIRA adopted a more socialist stance in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Sinn Féin, the political wing of the IRA, is overwhelmingly ‘Catholic’ but more strongly secular than the SDLP and has had an antagonistic relationship with the Catholic Church, which condemned its violence. Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness, the most prominent Sinn Féin leaders, are, however, both practising Catholics. Sinn Féin originally won support particularly in working-class areas but the IRA’s ceasefire and the peace process allowed more sceptical, middle-class nationalists to support Sinn Féin.

Provisional IRA (PIRA): formed from a split in the IRA in December 1969. The PIRA had become the dominant republican paramilitary group by the early 1970s and after 1972 was commonly referred to simply as the IRA.

Official IRA (OIRA): term used for the rump of the IRA after the split of late 1969/early 1970. The OIRA announced a ceasefire on 29 May 1972.

Republicans were involved in the founding of the civil rights movement and subsequent development, although this was not under republican control. Republicans sought to exploit the violence surrounding the attacks on the civil rights movement and the deployment of British troops to fight for Irish unity. The Provisional IRA took advantage of growing nationalist alienation from the increasingly repressive policies of the security forces to go on the offensive. The IRA argued that Ireland was Britain’s first and last colony and that the British should and would, inevitably, withdraw as they had from the rest of their Empire. As an interim measure the IRA supported the suspension of the Northern Ireland parliament and the introduction of direct rule in 1972. In negotiations with the British government in June 1972 republicans refused to compromise on their goal of a British declaration of its intent to withdraw and the creation of a federal Irish state, based on the four provinces of Ireland, including a nine-county Ulster. The IRA opposed the power-sharing settlement of 1974 and attempted to bring it down because it saw the project as shoring up British rule in Ireland. The SDLP were seen as ‘collaborators’ for participating in this British-inspired initiative.

Republicans tended to see unionists in two, highly contrasting ways. A civic republicanism would see unionists as an integral part of the Irish nation and emphasise the role that Irish Protestants had played in the anti-imperialist struggle against the ‘English’ invaders. The artificial partition of Ireland and the ‘marginal privileges’ that were given to unionists over their nationalist comrades in the North of Ireland had prevented the realisation of a united nation on the island of Ireland. The removal of the English presence would end these ‘marginal privileges’ and undermine the prop that sustained unionism in Ireland, and Irish Protestants would realise that they were Irish and not British after all. The unionists were the dupes or puppets of a manipulative British government, and freed from the puppet-master, unionists would embrace their future in a united Ireland. Alongside this inclusive strand of republicanism was a more sectarian exclusive variant. According to this perspective the Protestants of Ulster were an illegitimate colonial presence in Northern Ireland with all the features of a supremacist, settler mentality. A ‘British’ w...