![]()

1

The foundations of EC competition law

1.1 Introduction

Competition law is a rapidly developing area, fundamental to most legal systems. Despite its idiosyncratic and technical character, it influences numerous fields of law and itself draws heavily on principles of economics and politics. Its primary aim is to protect and encourage the competitive process, resulting in an optimum allocation of resources and the maximisation of consumer welfare. Bork points out: ‘antitrust was originally conceived as a limited intervention in free and private processes for the purpose of keeping these processes free’.1 In other words, competition law regulates market behaviour in order to preserve a free market economy. In a perfectly competitive market - i.e. one in which there are no barriers to entry or exit, where buyers and sellers of homogeneous products are plentiful, and where competitors have similar and very small market shares and there is total transparency - a system of competition law would be superfluous. This type of market is, however, almost impossible to find in practice, just as pure monopoly is unlikely to arise without state intervention. Most markets are placed between these two extremes and, in the absence of any form of control, undertakings are inclined to collude to fix prices, those in a dominant position misuse their market strength and mergers lead to excessive concentrations of economic power.2 All these practices hinder or impede the competitive process.

Competition law has played a prominent role in the development of EC law. In addition to the general objectives outlined above, it has also contributed significantly, and often controversially, to the consolidation of the single market objective of the Treaty. In the following pages the basic principles that underpin EC competition law will be considered.

1.2 The EC Treaty provisions in competition

Although the Preamble to the Treaty refers to the need to guarantee ‘steady expansion, balanced trade and fair competition’, the basis of EC competition policy is Article 3(g) EC. This Article provides that one of the activities intended to help the achievement of the aims of the Community is ‘the establishment of a system ensuring that competition in the internal market is not distorted’. Since this is a provision drafted in very general terms - as are many others in the Treaty - the Commission and Community judicature have been primarily responsible for the shaping of the aims and objectives of EC competition law.

Articles 81-89 EC establish a set of rules on competition and can be divided into two main groups: (a) those that focus on the activities of undertakings, and (b) those that focus on the activities of governments.

1.2.1 Rules concerning the activities of undertakings

Three provisions set out the parameters within which undertakings should operate to guarantee, as far as possible, the preservation of a competitive market:

1. Article 81 EC refers to anti–competitive behaviour that results from collusion between private undertakings. It prohibits agreements, decisions by associations of undertakings and concerted practices which may affect trade between Member States and that have the object or effect of preventing, restricting or distorting competition.

2. Article 82 EC aims to control abuses of dominant position, by one or more private undertakings, which may affect trade between Member States.

3. Article 86 EC sets out the rules that apply to public undertakings or to undertakings granted special rights.

The Treaty did not establish a specific legal basis for mergers between undertakings. The European Court of Justice (ECJ) in some of its early case law, considered the suitability of Articles 81 EC or 82 EC as the means of controlling mergers. In particular, its judgment in Continental Can v. Commission,3 supported the Commission’s use of Article 82 EC for these purposes.4 The adoption of the Merger Regulation in 1989, however, finally provided a separate substantive and procedural framework for the regulation of concentrations between undertakings.5

1.2.2 Rules concerning the activities of governments

Competition may be distorted not only by undertakings, but also by the action of a Member State, most commonly where the latter gives artificial competitive advantages to declining national industries. Article 87 EC lays down the principle that state aids are incompatible with EC law, unless otherwise provided in the Treaty. This provision also sets out some kinds of aid that are automatically6 or that may be permitted.7

1.2.3 Procedural rules

Article 83 EC provides that the Council will adopt appropriate regulations or directives to give effect to the principles in Articles 81 and 82 EC. On the basis of this provision, the Council enacted Regulation 17/62,8 which sets out the general procedure for the enforcement of Articles 81 and 82 EC at Community level. A radical reform of the system of enforcement provided in Regulation 17/62 was suggested by the Commission in its 1999 White Paper on enforcement.9 This crystallised in the recent proposal of the Commission for a draft enforcement regulation in September 2000.10 The current system of enforcement and the proposed reforms will be considered in detail in Chapter 4.

Moreover, certain sectors of the economy are the subject of special regulations, such as transport. 11 Likewise, mergers and state aids are subject to specific procedural rules set out respectively in the EC Merger regulation 12 and in Article 88 EC and its implementing regulation. 13

1.3 The scope of application of Articles 81 and 82 EC

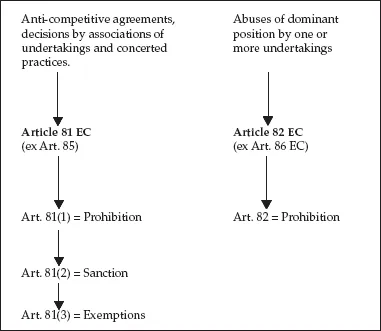

As this work focuses on Articles 81 and 82 EC, it seems necessary at the outset to understand the basic structure and scope of application of these two provisions. This is set out in Figure 1.1. 14

Article 81 EC deals with anti–competitive behaviour that results from collusion between undertakings. This provision therefore does not refer to unilateral but to bilateral or multilateral behaviour. It is divided into three paragraphs. The first lays down a general prohibition against anti–competitive forms of cooperation between undertakings. The second provides a sanction of nullity for the infringement of that prohibition. The third allows exemptions to be granted to forms of cooperation that come under the prohibition in the first paragraph, on account of their beneficial effects.

Figure 1.1 Scope of application of Articles 81 and 82 EC

Article 82 EC, by contrast, prohibits abuses of dominant position by one or more undertakings. As the Court expressed it in Continental Can,15 this provision concerns the unilateral activity of one or more undertakings. Even when more than one undertaking is involved - such as in the case of joint or collective dominance - their behaviour is still regarded as unilateral where they operate as a single economic unit which is dominant and abuse that position of dominance. The structure of Article 82 EC is simple: it comprises only a prohibition on abuses of dominant position and there is neither a provision for automatic nullity nor a provision for exemption equivalent to those in Article 81 EC.

Articles 81 and 82 EC will be considered in detail in Chapters 2 and 3 of this work respectively.

1.4 The two levels of enforcement of EC competition law: the roles of the Commission, the national courts and national authorities

Articles 81 and 82 EC are both enforced at Community level and at national level.

At Community level, the Commission is the enforcement authority, as provided by Article 85 EC, and its specific powers are laid down in Regulation 17/62. Under this regulation, the Commission may find that there has been an infringement of Article 81 or 82 EC and, as a result, impose fines or, alternatively, it may adopt decisions finding that there has been no breach of the competition rules. It may also grant exemptions16. Undertakings dissatisfied with Commission decisions may challenge them before the Court of First Instance and an appeal on points of law is available before the European Court of Justice.17

At national level, national courts and national competition authorities are competent to enforce competition law. 18 National courts derive their power to apply Articles 81(1) and (2) and Article 82 EC from the direct effect of these provisions.19 The power of enforcement of national competition authorities is founded in Articles 84 EC and 9(3) of Regulation 17/62.20 However, in the current system of enforcement, neither national courts nor national authorities can grant exemption or, in other words, apply Article 81(3) EC. This is because Article 9(1) of Regulation 17/62 granted the Commission the exclusive power to grant exemptions. One of the core reforms suggested by the Commission in its 1999 White Paper is that Article 81 EC, as a whole, should be directly applicable by national courts and national authorities.21

1.5 The aims of EC competition policy

In its XXIXth Report on Competition Policy, the Commission clearly set out the two principal objectives that underline Community Competition law:

The first objective of competition policy is the maintenance of competitive markets. Competition policy serves as an instrument to encourage industrial efficiency, the optimal allocation of resources, technical progress and the flexibility to adjust to a changing environment … The second is the single market objective … 22

Therefore, in addition to the general goals pursued by any competition system, EC c...