- 80 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book outlines a path towards a more practical era for "corporate responsibility", where companies make real environmental gains based on hard facts, using lifecycle assessment (LCA) and environmental product declarations (EPDs).By the time you have finished this book you will be able to make the case for moving from corporate to product sustainability and propose a methodology for doing this, based on EPDs.In the past decade, thousands of companies have started the journey towards sustainability, leading to a huge supporting industry of sustainability professionals, lorry-loads of corporate reports, and a plethora of green labels and marketing claims. Ramon Arratia argues that it's now time to transform this new industry by cutting out all the fluff and instead focusing on Full Product Transparency (FPT). In the world of FPT, companies carry out LCAs for all their products and services, identifying their biggest impacts and where they can make the greatest difference. They disclose the full environmental impacts of their products using easily-understood metrics, allowing customers to make meaningful comparisons in their purchasing decisions and providing governments with a platform to reward products and services with the lowest impacts.This book will help you put your company on a path towards Full Product Transparency. This is a decision that can revolutionize and align consumer behaviour, supply chains, policy-making and reporting. It is no less than the path to the future of all business.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Full Product Transparency by Ramon Arratia in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Ethics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

The Case for Refocusing on Product (Rather than Corporate) Sustainability

1. The corporate responsibility beauty contest hasn’t taken us that far

WE ARE AT LEAST TEN YEARS ALONG the corporate sustainability journey now, so what really significant changes have we achieved? Perhaps the business world has focused on the wrong tasks? Could it be that, despite all the carbon neutrality claims, hundreds of Global Reporting Initiative A+ reports and sustainability teams of ten or more people, companies have still not radically redesigned their core products and business models?

The answer is that there has been far too much focus on companies wanting to look good, and not nearly enough attention paid to actually performing well.

The beauty contest

It’s in the blood of companies to compete, to strive to be better than their peers. That has been the reason for the success of corporate sustainability, because businesses like to vie with each other to be the best in this area. But the end result of all the competition has been to encourage companies to give the impression of looking good while barely changing their ‘business as usual’ model. It’s hard to change the direction of a business, especially in the short term, but the corporate sustainability beauty contest has nonetheless been characterised by a disappointingly low level of achievement.

An entire industry has been created around this beauty contest, including thousands of labels, corporate responsibility (CR) report design agencies, boutique assurance providers, hundreds of awards with infinite categories, materiality matrix mavericks, investor questionnaires consultants, professional stakeholders looking to ‘engage’ with companies and all manner of membership organisations offering support networks for a hefty fee. Service-provider directories in the field typically feature more than 500 such organisations offering to help businesses look more virtuous than their peers-what the marketing guys call ‘differentiation’.

The problem with all this activity is that looking more virtuous doesn’t have anything to do with being more sustainable. We in the sustainability movement need to ask ourselves honestly whether we are pushing for actual change or whether we are merely helping companies to gloss over big issues by making them compete in irrelevant contests?

We offer companies the prospect of being able to make ‘100% natural’ products or to be the first company in their sector to become ‘carbon neutral’. In short, we have been tremendously innovative in coming up with fairly meaningless stuff that is easy and quick to implement, or that can deliver nice stories and marketing claims, but frighteningly ineffective at producing anything that will affect actual performance.

And astonishingly, CEOs are quite happy about their performance

A 2010 Accenture survey of global CEOs put the last nail in the coffin of CR as it stands. It found that 81% thought sustainability issues were fully embedded into the strategy and operations of their company. Yes, FULLY EMBEDDED! It’s not a joke. It’s actually quite sad that the most senior people don’t get it.

Please someone explain to them that having a CR team reporting to public affairs with a nicely designed 150k report with some cherry-picked case studies and a set of qualitative targets plus a few quantitative targets on quick wins is not ‘fully embedded’! Fully embedded means sustainability is fully taken account of in all the products of the company. You are redesigning your products, your business models, your entire value chain. Yet there is no company in the world that has achieved this. The sustainability movement should brutally tell CEOs that making wishy-washy claims such as ‘Sustainability is part of our DNA’ is just wrong.

Seventy-two percent of CEOs in the same survey felt the strongest motivator for taking action on sustainability issues was ‘strengthening brand, trust and reputation’. Well, here we have the reason we are trapped in this rather useless beauty contest.

Prepare yourself for the next sustainability phase: Full product transparency

Somebody needs to speak out if we are to move towards something more meaningful. We need a proper comparative benchmark, so that companies can compete on what really matters – and so that the sustainability consultancy industry can sell properly useful transformative services to these companies. This book is aimed at providing this benchmark: products instead of companies.

So the next phase in sustainability has to be truly embedded by being focused on the product. We need to understand clearly the total footprint of a product throughout its lifecycle – that must be the starting point.

There has been some focus at product level but wrongly headed: Green labels

You may well be asking, ‘Why does it have to be this complicated to choose the most sustainable product? Can’t I just look for a product with a green label?’

It’s not surprising people look for shortcuts to help them decide. After all, few of us have the time to study every purchase we make. That’s why there have been so many people, from gurus, to NGOs, to certification sharks, to industry associations inventing so many lucrative labels that offer ‘quick assurance’ about product sustainability credentials.

But when you look carefully at how some labels are administered, you realise how flawed they are. Most are too easy to obtain, which is obvious because the easier your label is to get, the bigger your market becomes. Most labels are very narrow in scope, measuring the easiest things to measure rather than the big issues. Many lack independent certification or may even be administered by the manufacturers themselves. Many labels duplicate each other, confusing clients and obliging manufacturers to certify the same product several times. Unfortunately, some of the best marketed labels are the least robust.

Today nobody certifies whether a yoghurt or a burger is good for your health. You just get the calories and the nutrition facts and you judge. This is what this book is arguing for: the environmental impacts of products – full product transparency.

2. It’s about products, not companies!

If you read corporate sustainability reports, you’ll find that most companies still focus primarily on the environmental performance of their own operations. Yet for many businesses this focus is mismatched with their true impacts, which lie outside their operations and fall instead within the lifecycle of their products.

When you view a company in terms of the products it makes – as opposed to its offices and employees – you soon discover that the vast majority of environmental impacts occur outside its operational boundaries. In many cases the impacts associated with raw materials extraction and processing, product use and end life far outstrip any ‘in-house’ impacts.

Most of the impacts are outside companies’ boundaries

For Interface’s carpet tiles, for example, around 68% of the impact is associated with the production of raw materials, while only around 10% can be attributed to in-house operations. For companies that make energy-guzzling machines, by far the biggest impact is during the product use phase. This is counterintuitive for many people, because the most visible parts of a company’s operations are either their glitzy office headquarters or their smoke-belching factories.

Sometimes the figures can be quite spectacular. For a consumer goods company such as Unilever, around 95% of a product’s impacts typically come from outside the company’s own operations (see figure below).

FIGURE 1. Unilever product impacts

SOURCE: Unilever 2008 baseline study across 14 countries. Total in tonnes.

SOURCE: Unilever 2008 baseline study across 14 countries. Total in tonnes.

Tesco, a UK supermarket, says its direct carbon footprint in the UK is 2.6 million tonnes of CO2 per year. Yet the impact of its supply chain, which makes the products that go into its shops, is 26 million tonnes of CO2 – ten times Tesco’s own footprint. And the footprint of its customers using Tesco’s products is even greater: 228 million tonnes of CO2, which is not far off 100 times the supermarket chain’s own footprint.

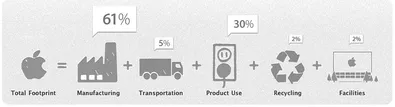

FIGURE 2. Apple’s environmental footprint

SOURCE: Apple, www.apple.com/environment

SOURCE: Apple, www.apple.com/environment

Only 2% of Apple’s carbon footprint comes directly from its offices and facilities, while around 61% comes from outsourced manufacturing and raw materials, and 30% from the product when it is being used by the consumer.

The impact of ‘stuff’ is usually in the supply chain

When a lifecycle assessment is carried out on a physical product such as a carpet, or a t-shirt, or some ready-mixed concrete, it usually shows that the biggest impacts are in the supply chain, and are therefore already embedded in the product before they get to the company for the final manufacturing process. The biggest environmental impacts up to this point are usually associated with the types of raw materials being used, as well as the types of chemicals used to process these raw materials.

Outsourcing has made things worse

With the advent of outsourcing over the past 20 years, we now have many brands that consist essentially of a marketing department, some finance people, HR and legal units, and a product design team. The actual manufacturing of the product happens halfway across the world in nations such as China, India, Turkey or Brazil, because it’s cheaper to manufacture in such places rather than in Europe or the US. This explains why so many lifecycle analyses of products show an increasing percentage of the impacts taking place outside the operations of a company.

The mismatch in management: 80% of management on direct impacts

So the bottom line is that the seemingly impressive corporate responsibility programmes and targets of many companies are in fact generally confined to minor issues, often down to the paltry level of office paper or electricity. These misinformed programmes take the attention and focus away from major issues such as raw materials use, in life product energy usage, toxic chemicals use and end of life disposal/reuse. These are the main impacts of a company that makes products, not their office lighting. The legendary green advocate Jim Fava, from Five Winds/PE International, made this crude point in a Green Mondays event in June 2011: he pointed out that 80% of sustainability management tools focus upon only 20% of the actual environmental impacts.

The key to sustainability lies in product design

The key to radical change, then, is through product design. If the impact is mainly in the raw materials, then by redesigning its products a company can use fewer raw materials, or use alternatives to them. If a product is a machine that consumes energy such as a car or a vacuum clean...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Abstract

- About The Author

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- 1 The Case for Refocusing on Product (Rather than Corporate) Sustainability

- 2 What is Full Product Transparency and How Do You Go About It?

- 3 How Full Product Transparency will Revolutionise Business Relations with Consumers, Investors, Policy-Makers and Society